Reconstruct Market Boundaries

HE FIRST PRINCIPLE of blue ocean strategy is to reconstruct market boundaries to break from the competition and create blue oceans. This principle addresses the search risk many companies struggle with. The challenge is to successfully identify, out of the haystack of possibilities that exist, commercially compelling blue ocean opportunities. This challenge is key because managers cannot afford to be riverboat gamblers betting their strategy on intuition or on a random drawing.

HE FIRST PRINCIPLE of blue ocean strategy is to reconstruct market boundaries to break from the competition and create blue oceans. This principle addresses the search risk many companies struggle with. The challenge is to successfully identify, out of the haystack of possibilities that exist, commercially compelling blue ocean opportunities. This challenge is key because managers cannot afford to be riverboat gamblers betting their strategy on intuition or on a random drawing.

In conducting our research, we sought to discover whether there were systematic patterns for reconstructing market boundaries to create blue oceans. And, if there were, we wanted to know whether these patterns applied across all types of industry sectors from consumer goods, to industrial products, to finance and services, to telecoms and IT, to pharmaceuticals and B213—or were they limited to specific industries?

We found clear patterns for creating blue oceans. Specifically, we found six basic approaches to remaking market boundaries. We call this the six paths framework. These paths have general applicability across industry sectors, and they lead companies into the corridor of commercially viable blue ocean ideas. None of these paths requires special vision or foresight about the future. All are based on looking at familiar data from a new perspective.

These paths challenge the six fundamental assumptions underlying many companies' strategies. These six assumptions, on which most companies hypnotically build their strategies, keep companies trapped competing in red oceans. Specifically, companies tend to do the following:

• Define their industry similarly and focus on being the best within it

• Look at their industries through the lens of generally accepted strategic groups (such as luxury automobiles, economy cars, and family vehicles), and strive to stand out in the strategic group they play in

• Focus on the same buyer group, be it the purchaser (as in the office equipment industry), the user (as in the clothing industry), or the influencer (as in the pharmaceutical industry)

• Define the scope of the products and services offered by their industry similarly

• Accept their industry's functional or emotional orientation

• Focus on the same point in time and often on current competitive threats in formulating strategy

The more that companies share this conventional wisdom about how they compete, the greater the competitive convergence among them.

To break out of red oceans, companies must break out of the accepted boundaries that define how they compete. Instead of looking within these boundaries, managers need to look systematically across them to create blue oceans. They need to look across alternative industries, across strategic groups, across buyer groups, across complementary product and service offerings, across the functionalemotional orientation of an industry, and even across time. This gives companies keen insight into how to reconstruct market realities to open up blue oceans. Let's examine how each of these six paths works.

Path 1: Look Across Alternative Industries

In the broadest sense, a company competes not only with the other firms in its own industry but also with companies in those other industries that produce alternative products or services. Alternatives are broader than substitutes. Products or services that have different forms but offer the same functionality or core utility are often substitutes for each other. On the other hand, alternatives include products or services that have different functions and forms but the same purpose.

For example, to sort out their personal finances, people can buy and install a financial software package, hire a CPA, or simply use pencil and paper. The software, the CPA, and the pencil are largely substitutes for each other. They have very different forms but serve the same function: helping people manage their financial affairs.

In contrast, products or services can take different forms and perform different functions but serve the same objective. Consider cinemas versus restaurants. Restaurants have few physical features in common with cinemas and serve a distinct function: They provide conversational and gastronomical pleasure. This is a very different experience from the visual entertainment offered by cinemas. Despite the differences in form and function, however, people go to a restaurant for the same objective that they go to the movies: to enjoy a night out. These are not substitutes, but alternatives to choose from.

In making every purchase decision, buyers implicitly weigh alternatives, often unconsciously. Do you need a self-indulgent two hours? What should you do to achieve it? Do you go to movie, have a massage, or enjoy reading a favorite book at a local cafe? The thought process is intuitive for individual consumers and industrial buyers alike.

For some reason, we often abandon this intuitive thinking when we become sellers. Rarely do sellers think consciously about how their customers make trade-offs across alternative industries. A shift in price, a change in model, even a new ad campaign can elicit a tremendous response from rivals within an industry, but the same actions in an alternative industry usually go unnoticed. Trade journals, trade shows, and consumer rating reports reinforce the vertical walls between one industry and another. Often, however, the space between alternative industries provides opportunities for value innovation.

Consider NetJets, which created the blue ocean of fractional jet ownership. In less than twenty years NetJets has grown larger than many airlines, with more than five hundred aircraft, operating more than two hundred fifty thousand flights to more than one hundred forty countries. Purchased by Berkshire Hathaway in 1998, today NetJets is a multibillion-dollar business, with revenues growing at 30-35 percent per year from 1993 to 2000. NetJets' success has been attributed to its flexibility, shortened travel time, hasslefree travel experience, increased reliability, and strategic pricing. The reality is that NetJets reconstructed market boundaries to create this blue ocean by looking across alternative industries.

The most lucrative mass of customers in the aviation industry are corporate travelers. NetJets looked at the existing alternatives and found that when business travelers want to fly, they have two principal choices. On the one hand, a company's executives can fly business class or first class on a commercial airline. On the other hand, a company can purchase its own aircraft to serve its corporate travel needs. The strategic question is, Why would corporations choose one alternative industry over another? By focusing on the key factors that lead corporations to trade across alternatives and eliminating or reducing everything else, NetJets created its blue ocean strategy.

Consider this: Why do corporations choose to use commercial airlines for their corporate travel? Surely it's not because of the long check-in and security lines, hectic flight transfers, overnight stays, or congested airports. Rather, they choose commercial airlines for only one reason: costs. On the one hand, commercial travel avoids the high up-front, fixed-cost investment of a multimilliondollar jet aircraft. On the other hand, a company purchases only the number of corporate airline tickets needed per year, lowering variable costs and reducing the possibility of unused aviation travel time that often accompanies the ownership of corporate jets.

So NetJets offers its customers one-sixteenth ownership of an aircraft to be shared with fifteen other customers, each one entitled to fifty hours of flight time per year. Starting at $375,000 (plus pilot, maintenance, and other monthly costs), owners can purchase a share in a $6 million aircraft.' Customers get the convenience of a private jet at the price of a commercial airline ticket. Comparing firstclass travel with private aircraft, the National Business Aviation Association found that when direct and indirect costs hotel, meals, travel time, expenses were factored in, the cost of firstclass commercial travel was significantly higher. In a cost-benefit analysis for four passengers on a theoretical trip from Newark to Austin, the real cost of the commercial trip was $19,400, compared with $10,100 in a private jet.2 As for NetJets, it avoids the enormous fixed costs that commercial airlines attempt to cover by filling larger and larger aircraft. NetJets' smaller airplanes, the use of smaller regional airports, and limited staff keep costs to a minimum.

To understand the rest of the NetJets formula, consider the flip side: Why do people choose corporate jets over commercial travel? Certainly it is not to pay the multimilliondollar price to purchase planes. Nor is it to set up a dedicated flight department to take care of scheduling and other administrative matters. Nor it is to pay socalled deadhead costs the costs of flying the aircraft from its home base to where it is needed. Rather, corporations buy private jets to dramatically cut total travel time, to reduce the hassle of congested airports, to allow for pointto-point travel, and to gain the benefit of having more productive and energized executives who can hit the ground running upon arrival. So NetJets built on these distinctive strengths. Whereas 70 percent of commercial flights went to only thirty airports across the United States, NetJets offered access to more than five thousand five hundred airports across the country, in convenient locations near business centers. On international flights, your plane pulls directly up to the customs office.

With pointto-point service and the exponential increase in the number of airports to land in, there are no flight transfers; trips that would otherwise require overnight stays can be completed in a single day. The time from your car to takeoff is measured in minutes instead of hours. For example, whereas a flight from Washington, D.C., to Sacramento would take 10.5 hours on a commercial airline, it is only 5.2 hours on a NetJets aircraft; from Palm Springs to Cabo San Lucas takes 6 hours commercial, and only 2.1 hours via NetJets.3 NetJets offers substantial cost savings in total travel time.

Perhaps most appealing, your jet is always available with only four hours' notice. If a jet is not available, NetJets will charter one for you. Last but not least, NetJets dramatically reduces issues related to security threats and offers clients customized in-flight service, such as having your favorite food and beverages ready for you when you board.

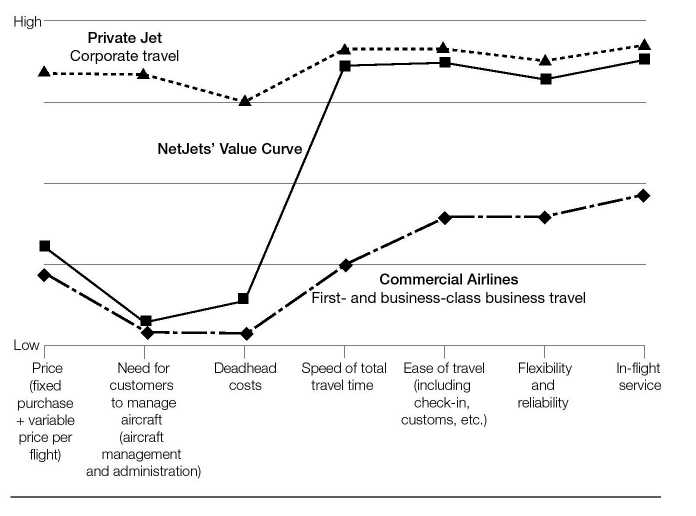

By offering the best of commercial travel and private jets and eliminating and reducing everything else, NetJets opened up a multibillion-dollar blue ocean wherein customers get the convenience and speed of a private jet with a low fixed cost and the low variable cost of commercial airline travel (see figure 3-1). And the competition? According to NetJets, in the past seven years fiftyseven companies have set up fractional jet operations; of those, fiftyseven have gone out of business.

The biggest telecommunications success in Japan since the 1980s also has its roots in path 1. Here we are speaking of NTT DoCoMo's i-mode, which was launched in 1999. The i-mode service changed the way people communicate and access information in Japan. NTT DoCoMo's insight into creating a blue ocean came by thinking about why people trade-across the alternatives of mobile phones and the Internet. With deregulation of the Japanese tele communications industry, new competitors were entering the market and price competition and technological races were the norm. The result was that costs were rising while the average revenue per user fell. NTT DoCoMo broke out of this red ocean of bloody competition by creating a blue ocean of wireless transmission not only of voice but also of text, data, and pictures.

FIGURE 3-1

The Strategy Canvas of NetJets

NTT DoCoMo asked, What are the distinctive strengths of the Internet over cell phones, and vice versa? Although the Internet offered endless information and services, the killer apps were e-mail, simple information (such as news, weather forecasts, and a telephone directory), and entertainment (including games, events, and music entertainment). The key downside of the Internet was the far higher price of computer hardware, an overload of information, the nuisance of dialing up to go online, and the fear of giving credit card information electronically. On the other hand, the distinctive strengths of mobile phones were their mobility, voice transmission, and ease of use.

NTT DoCoMo broke the trade-off between these two alternatives, not by creating new technology but by focusing on the decisive advantages that the Internet has over the cell phone and vice versa. The company eliminated or reduced everything else. Its userfriendly interface has one simple button, the i-mode button (i standing for interactive, Internet, information, and the English pronoun 1), which users press to give them immediate access to the few killer apps of the Internet. Instead of barraging you with infinite information as on the Internet, however, the i-mode button acts as a hotel concierge service, connecting only to preselected and preapproved sites for the most popular Internet applications. That makes navigation fast and easy. At the same time, even though the i-mode phone is priced 25 percent higher than a regular cell phone, the price of the i-mode phone is dramatically less than that of a PC, and its mobility is high.

Moreover, beyond adding voice, the i-mode uses a simple billing service whereby all the services used on the Web via the 1-mode are billed to the user on the same monthly bill. This dramatically reduces the number of bills users receive and eliminates the need to give credit card details, as on the Internet. And because the i-mode service is automatically turned on whenever the phone is on, users are always connected and have no need to go through the hassle of logging on.

Neither the standard cell phone nor the PC could compete with i-mode's divergent value curve. By the end of 2003 the number of i-mode subscribers had reached 40.1 million, and revenues from the transmission of data, pictures, and text increased from 295 million yen ($2.6 million) in 1999 to 886.3 billion yen ($8 billion) in 2003. The i-mode service did not simply win customers from competitors. It dramatically grew the market, drawing in youth and senior citizens and converting voice-only customers to voice and data transmission customers.

Ironically, European and U.S. counterparts who have been scrambling to unlock a similar blue ocean in the West have so far failed. Why? Our assessment shows that they have been focused on delivering the most sophisticated technology, WAP (wireless application protocol), instead of delivering exceptional value. This has led them to build overcomplicated offerings that miss the key commonalities valued by the mass of people.

Many other well-known success stories have looked across alternatives to create new markets. The Home Depot offers the expertise of professional home contractors at markedly lower prices than hardware stores. By delivering the decisive advantages of both alternative industries and eliminating or reducing everything else The Home Depot has transformed enormous latent demand for home improvement into real demand, making ordinary homeowners into do-it-yourselfers. Southwest Airlines concentrated on driving as the alternative to flying, providing the speed of air travel at the price of car travel and creating the blue ocean of short-haul air travel. Similarly, Intuit looked to the pencil as the chief alternative to personal financial software to develop the fun and intuitive Quicken software.

What are the alternative industries to your industry? Why do customers trade across them? By focusing on the key factors that lead buyers to trade across alternative industries and eliminating or reducing everything else, you can create a blue ocean of new market space.

Path 2: Look Across Strategic Groups Within Industries

Just as blue oceans can often be created by looking across alternative industries, so can they be unlocked by looking across strategic groups. The term refers to a group of companies within an industry that pursue a similar strategy. In most industries, the fundamental strategic differences among industry players are captured by a small number of strategic groups.

Strategic groups can generally be ranked in a rough hierarchical order built on two dimensions: price and performance. Each jump in price tends to bring a corresponding jump in some dimensions of performance. Most companies focus on improving their competitive position within a strategic group. Mercedes, BMW, and Jaguar, for example, focus on outcompeting one another in the luxury car segment as economy car makers focus on excelling over one another in their strategic group. Neither strategic group, however, pays much heed to what the other is doing because from a supply point of view they do not seem to be competing.

The key to creating a blue ocean across existing strategic groups is to break out of this narrow tunnel vision by understanding which factors determine customers' decisions to trade up or down from one group to another.

Consider Curves, the Texas-based women's fitness company. Since franchising began in 1995, Curves has grown like wildfire, acquiring more than two million members in more than six thousand locations, with total revenues exceeding the $1 billion mark. A new Curves opens, on average, every four hours somewhere in the world.

What's more, this growth was triggered almost entirely through word of mouth and buddy referrals. Yet, at its inception, Curves was seen as entering an oversaturated market, gearing its offering to customers who would not want it, and making its offering significantly blander than the competition's. In reality, however, Curves exploded demand in the U.S. fitness industry, unlocking a huge untapped market, a veritable blue ocean of women struggling and failing to keep in shape through sound fitness. Curves built on the decisive advantages of two strategic groups in the U.S. fitness industry-traditional health clubs and home exercise programs and eliminated or reduced everything else.

At the one extreme, the U.S. fitness industry is awash with traditional health clubs that catered to both men and women, offering a full range of exercise and sporting options, usually in upscale urban locations. Their trendy facilities are designed to attract the high-end health club set. They have the full range of aerobic and strength training machines, a juice bar, instructors, and a full locker room with showers and sauna, because the aim is for customers to spend social as well as exercise time there. Having fought their way across town to health clubs, customers typically spend at least an hour there, and more often two. Membership fees for all this are typically in the range of $100 per month not cheap, guaranteeing that the market would stay upscale and small. Traditional health club customers represent only 12 percent of the entire population, concentrated overwhelmingly in the larger urban areas. Investment costs for a traditional full-service health club run from $500,000 to more than $1 million, depending on the city center location.

At the other extreme is the strategic group of home exercise programs, such as exercise videos, books, and magazines. These are a small fraction of the cost, are used at home, and generally require little or no exercise equipment. Instruction is minimal, being confined to the star of the exercise video or book and magazine explanations and illustrations.

The question is, What makes women trade either up or down between traditional health clubs and home exercise programs? Most women don't trade up to health clubs for the profusion of special machines, juice bars, locker rooms with sauna, pool, and the chance to meet men. The average female nonathlete does not even want to run into men when she is working out, perhaps revealing lumps in her leotards. She is not inspired to line up behind machines in which she needs to change weights and adjust their incline angles. As for time, it has become an increasingly scarce commodity for the average woman. Few can afford to spend one to two hours at a health club several times a week. For the mass of women, the city center locations also present traffic challenges, something that increases stress and discourages going to the gym.

It turns out that most women trade up to health clubs for one principal reason. When they are at home it's too easy to find an excuse for not working out. It is hard to be disciplined in the confines of one's home if you are not already a committed sports enthusiast. Working out collectively, instead of alone, is more motivating and inspiring. Conversely, women who use home exercise programs do so primarily for the time saving, lower costs, and privacy.

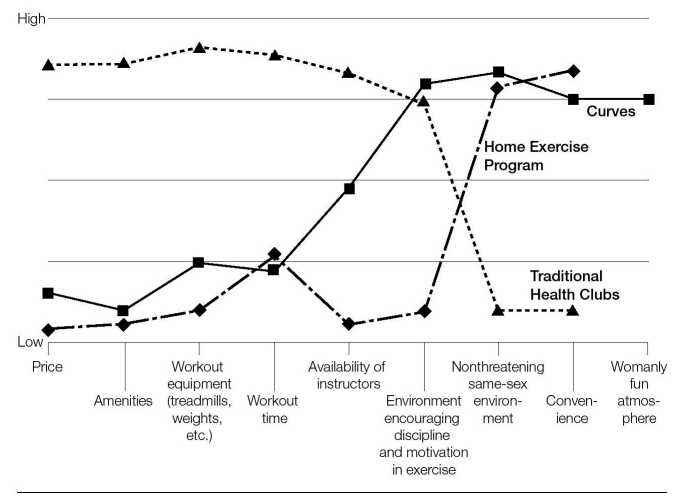

Curves built its blue ocean by drawing on the distinctive strengths of these two strategic groups, eliminating and reducing everything else (see figure 3-2). Curves has eliminated all the aspects of the traditional health club that are of little interest to the broad mass of women. Gone are the profusion of special machines, food, spa, pool, and even locker rooms, which have been replaced by a few curtainedoff changing areas.

The experience in a Curves club is entirely different from that in a typical health club. The member enters the exercise room where the machines (typically about ten) are arranged, not in rows facing a television as in the health club, but in a circle to facilitate interchange among members, making the experience fun. The QuickFit circuit training system uses hydraulic exercise machines, which need no adjusting, are safe, simple to use, and nonthreatening. Specifically designed for women, these machines reduce impact stress and build strength and muscle. While exercising, members can talk and support one another, and the social, nonjudgmental atmosphere is totally different from that of a typical health club. There are few if any mirrors on the wall, and there are no men staring at you. Members move around the circle of machines and aerobic pads and in thirty minutes complete the whole workout. The result of reducing and focusing service on the essentials is that prices fall to around $30 per month, opening the market to the broad mass of women. Curves' tagline could be "for the price of a cup of coffee a day you can obtain the gift of health through proper exercise.

Curves offers the distinctive value depicted in figure 3-2 at a lower cost. Compared with the start-up investment of $500,000 to $1 million for traditional health clubs, start-up investments for Curves are in the range of only $25,000 to $30,000 (excluding a $20,000 franchise fee) because of the wide range of factors the company eliminated. Variable costs are also significantly lower, with personnel and maintenance of facilities dramatically reduced and rent reduced because of the much smaller spaces required: 1,500 square feet in nonprime suburban locations versus 35,000 to 100,000 square feet in prime urban locations. Curves' low-cost business model makes its franchises easy to afford and helps explain why they have mushroomed quickly. Most franchises are profitable within a few months, as soon as they recruit on average one hundred members. Established Curves franchises are selling in the range of $100,000 to $150,000 on the secondary market.

FIGURE 3-2

The Strategy Canvas of Curves

The result is that Curves facilities are everywhere in most towns of any size. Curves is not competing directly with other health and exercise concepts; it created new blue ocean demand. As the United States and North America become saturated, management has plans to expand into Europe. Expansion has already begun in Latin America and Spain. By the end of 2004, Curves is expected to reach eight thousand five hundred fitness centers.

Beyond Curves, many companies have created blue oceans by looking across strategic groups. Ralph Lauren created the blue ocean of "high fashion with no fashion." Its designer name, the elegance of its stores, and the luxury of its materials capture what most customers value in haute couture. At the same time, its updated classical look and price capture the best of the classical lines such as Brooks Brothers and Burberry. By combining the most attractive factors of both groups and eliminating or reducing everything else, Polo Ralph Lauren not only captured share from both segments but also drew many new customers into the market.

In the luxury car market, Toyota's Lexus carved out a new blue ocean by offering the quality of the high-end Mercedes, BMW, and Jaguar at a price closer to the lower-end Cadillac and Lincoln. And think of the Sony Walkman. By looking across the high fidelity of boom boxes with the low price and mobility of transistor radios within the audio equipment industry, Sony created the personal portable-stereo market in the late 1970s. The Walkman took share from these two strategic groups. In addition, its leap in value drew new customers, including joggers and commuters, into this blue ocean.

Michigan-based Champion Enterprises identified a similar opportunity by looking across two strategic groups in the housing industry: makers of prefabricated housing and on-site developers. Prefabricated houses are cheap and quick to build, but they are also dismally standardized and have a low-quality image. Houses built by developers on-site offer variety and an image of high quality but are dramatically more expensive and take longer to build.

Champion created a blue ocean by offering the decisive advantages of both strategic groups. Its prefabricated houses are quick to build and benefit from tremendous economies of scale and lower costs, but Champion also allows buyers to choose such high-end finishing touches as fireplaces, skylights, and even vaulted ceilings to give the homes a personal feel. In essence, Champion has changed the definition of prefabricated housing. As a result, far more lowerto middle-income buyers have become interested in purchasing pre fabricated housing rather than renting or buying an apartment, and even some affluent people are being drawn into the market.

What are the strategic groups in your industry? Why do customers trade up for the higher group, and why do they trade down for the lower one?

Path 3: Look Across the Chain of Buyers

In most industries, competitors converge around a common definition of who the target buyer is. In reality, though, there is a chain of "buyers" who are directly or indirectly involved in the buying decision. The purchasers who pay for the product or service may differ from the actual users, and in some cases there are important influencers as well. Although these three groups may overlap, they often differ. When they do, they frequently hold different definitions of value. A corporate purchasing agent, for example, may be more concerned with costs than the corporate user, who is likely to be far more concerned with ease of use. Similarly, a retailer may value a manufacturer's just-in-time stock replenishment and innovative financing. But consumer purchasers, although strongly influenced by the channel, do not value these things.

Individual companies in an industry often target different customer segments for example, large versus small customers. But an industry typically converges on a single buyer group. The pharmaceutical industry, for example, focuses overridingly on influencers: doctors. The office equipment industry focuses heavily on purchasers: corporate purchasing departments. And the clothing industry sells predominantly to users. Sometimes there is a strong economic rationale for this focus. But often it is the result of industry practices that have never been questioned.

Challenging an industry's conventional wisdom about which buyer group to target can lead to the discovery of new blue ocean. By looking across buyer groups, companies can gain new insights into how to redesign their value curves to focus on a previously overlooked set of buyers.

Think of Novo Nordisk, the Danish insulin producer that created a blue ocean in the insulin industry. Insulin is used by diabetics to regulate the level of sugar in their blood. Historically, the insulin industry, like most of the pharmaceutical industry, focused its attention on the key influencers: doctors. The importance of doctors in affecting the insulin purchasing decision of diabetics made doctors the target buyer group of the industry. Accordingly, the industry geared its attention and efforts to produce purer insulin in response to doctors' quest for better medication. The issue was that innovations in purification technology had improved dramatically by the early 1980s. As long as the purity of insulin was the major parameter upon which companies competed, little progress could be made further in that direction. Novo itself had already created the first "human monocomponent" insulin that was a chemically exact copy of human insulin. Competitive convergence among the major players was rapidly occurring.

Novo Nordisk, however, saw that it could break away from the competition and create a blue ocean by shifting the industry's longstanding focus on doctors to the users patients themselves. In focusing on patients, Novo Nordisk found that insulin, which was supplied to diabetes patients in vials, presented significant challenges in administering. Vials left the patient with the complex and unpleasant task of handling syringes, needles, and insulin, and of administering doses according to his or her needs. Needles and syringes also evoked unpleasant feelings of social stigmatism for patients. And patients did not want to fiddle with syringes and needles outside their homes, a frequent occurrence because many patients must inject insulin several times a day.

This led Novo Nordisk to the blue ocean opportunity of NovoPen, launched in 1985. NovoPen, the first userfriendly insulin delivery solution, was designed to remove the hassle and embarrassment of administering insulin. The NovoPen resembled a fountain pen; it contained an insulin cartridge that allowed the patient to easily carry, in one self-contained unit, roughly a week's worth of insulin. The pen had an integrated click mechanism, making it possible for even blind patients to control the dosing and administer insulin. Patients could take the pen with them and inject insulin with ease and convenience without the embarrassing complexity of syringes and needles.

To dominate the blue ocean it had unlocked, Novo Nordisk followed up by introducing, in 1989, NovoLet, a prefilled disposable insulin injection pen with a dosing system that provided users with even greater convenience and ease of use. And in 1999 it brought out the Innovo, an integrated electronic memory and cartridgebased delivery system. Innovo was designed to manage the delivery of insulin through built-in memory and to display the dose, the last dose, and the elapsed time information that is critical for reducing risk and eliminating worries about missing a dose.

Novo Nordisk's blue ocean strategy shifted the industry landscape and transformed the company from an insulin producer to a diabetes care company. NovoPen and the later delivery systems swept over the insulin market. Sales of insulin in prefilled devices or pens now account for the dominant share in Europe and Japan, where patients are advised to take frequent injections of insulin every day. Although Novo Nordisk itself has more than a 60 percent share in Europe and 80 percent in Japan, 70 percent of its total turnover comes from diabetes care, an offering that originated largely in the company's thinking in terms of users rather than influencers.

Similarly, consider Bloomberg. In a little more than a decade, Bloomberg became one of the largest and most profitable businessinformation providers in the world. Until Bloomberg's debut in the early 1980s, Reuters and Telerate dominated the online financialinformation industry, providing news and prices in real time to the brokerage and investment community. The industry focused on purchasers-IT managers who valued standardized systems, which made their lives easier.

This made no sense to Bloomberg. Traders and analysts, not IT managers, make or lose millions of dollars for their employers each day. Profit opportunities come from disparities in information. When markets are active, traders and analysts must make rapid decisions. Every second counts.

So Bloomberg designed a system specifically to offer traders better value, one with easy-to-use terminals and keyboards labeled with familiar financial terms. The systems also have two flat-panel monitors so that traders can see all the information they need at once without having to open and close numerous windows. Because traders must analyze information before they act, Bloomberg added a built-in analytic capability that works with the press of a button. Before, traders and analysts had to download data and use a pencil and calculators to perform important financial calculations. Now users can quickly run "what if" scenarios to compute returns on alternative investments, and they can perform longitudinal analyses of historical data.

By focusing on users, Bloomberg was also able to see the paradox of traders' and analysts' personal lives. They have tremendous income but work such long hours that they have little time to spend it. Realizing that markets have slow times during the day when little trading takes place, Bloomberg decided to add information and purchasing services aimed at enhancing traders' personal lives. Traders can use these services to buy items such as flowers, clothing, and jewelry; make travel arrangements; get information about wines; or search through real estate listings.

By shifting its focus upstream from purchasers to users, Bloomberg created a value curve that was radically different from anything the industry had seen before. The traders and analysts wielded their power within their firms to force IT managers to purchase Bloomberg terminals.

Many industries afford similar opportunities to create blue oceans. By questioning conventional definitions of who can and should be the target buyer, companies can often see fundamentally new ways to unlock value. Consider how Canon copiers created the small desktop copier industry by shifting the target customer of the copier industry from corporate purchasers to users. Or how SAP shifted the customer focus of the business application software industry from the functional user to the corporate purchaser to create its enormously successful real-time integrated software business.

What is the chain of buyers in your industry? Which buyer group does your industry typically focus on? If you shifted the buyer group of your industry, how could you unlock new value?

Path 4: Look Across Complementary Product and Service Offerings

Few products and services are used in a vacuum. In most cases, other products and services affect their value. But in most industries, rivals converge within the bounds of their industry's product and service offerings. Take movie theaters. The ease and cost of getting a babysitter and parking the car affect the perceived value of going to the movies. Yet these complementary services are beyond the bounds of the movie theater industry as it has been traditionally defined. Few cinema operators worry about how hard or costly it is for people to get babysitters. But they should, because it affects demand for their business. Imagine a movie theater with a babysitting service.

Untapped value is often hidden in complementary products and services. The key is to define the total solution buyers seek when they choose a product or service. A simple way to do so is to think about what happens before, during, and after your product is used. Babysitting and parking the car are needed before people can go to the movies. Operating and application software are used along with computer hardware. In the airline industry, ground transportation is used after the flight but is clearly part of what the customer needs to travel from one place to another.

Consider NABI, a Hungarian bus company. It applied path 4 to the $1 billion U.S. transit bus industry. The major customers in the industry are public transport properties (PTPs), municipally owned transportation companies serving fixed-route public bus transportation in major cities or counties.

Under the accepted rules of competition in the industry, companies competed to offer the lowest purchase price. Designs were outdated, delivery times were late, quality was low, and the price of options was prohibitive given the industry's penny-pinching approach. To NABI, however, none of this made sense. Why were bus companies focused only on the initial purchase price of the bus, when municipalities kept buses in circulation for twelve years on average? When it framed the market in this way, NABI saw insights that had escaped the entire industry.

NABI discovered that the highest-cost element to municipalities was not the price of the bus per se, the factor the whole industry competed on, but rather the costs that came after the bus was purchased: the maintenance of running the bus over its twelve-year life cycle. Repairs after traffic accidents, fuel usage, wear and tear on parts that frequently needed to be replaced due to the bus's heavy weight, preventive body work to stop rusting, and the like these were the highest-cost factors to municipalities. With new demands for clean air being placed on municipalities, the cost for public transport not being environmentally friendly was also beginning to be felt. Yet despite all these costs, which outstripped the initial bus price, the industry had virtually overlooked the complementary activity of maintenance and life-cycle costs.

This made NABI realize that the transit bus industry did not have to be a commodity-price-driven industry but that bus companies, focusing on selling buses at the lowest possible price, had made it that way. By looking at the total solution of complementary activities, NABI created a bus unlike any the industry had seen before. Buses were normally made from steel, which was heavy, corrosive, and hard to repair after accidents because entire panels had to be replaced. NABI adopted fiberglass in making its buses, a practice that killed five birds with one stone. Fiberglass bodies substantially cut the costs of preventive maintenance by being corrosion-free. It made body repairs faster, cheaper, and eas ier because fiberglass does not require panel replacements for dents and accidents; rather, damaged parts are simply cut out and new fiberglass materials are easily soldered. At the same time, its light weight (30-35 percent lighter than steel) cut fuel consumption and emissions substantially, making the buses more environmentally friendly. Moreover, its light weight allowed NABI to use not only lower-powered engines but also fewer axles, resulting in lower manufacturing costs and more space inside the bus.

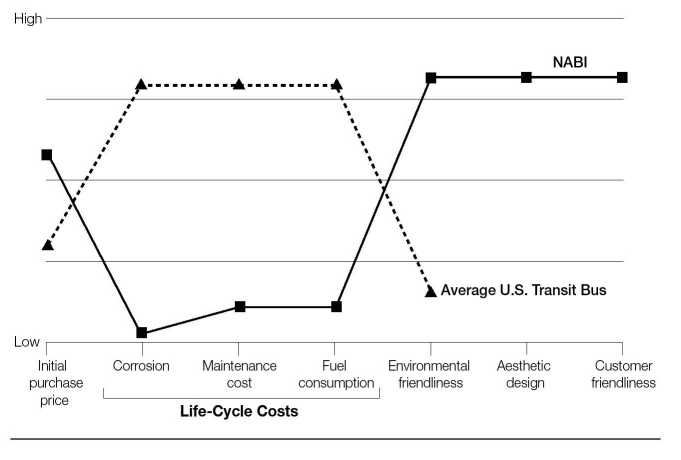

In this way, NABI created a value curve that is radically divergent from the industry's average curve. As you can see in figure 3-3, by building its buses in lightweight fiberglass, NABI eliminated or significantly reduced costs related to corrosion prevention, maintenance, and fuel consumption. As a result, even though NABI charged a higher initial purchase price than the average price of the industry, it offered its buses at a much lower life-cycle cost to municipalities. With much lighter emissions, the NABI buses raised the level of environmental friendliness high above the industry standard. Moreover, the higher price NABI charged allowed it to create factors unprecedented in the industry, such as modern aesthetic design and customer friendliness, including lower floors for easy mounting and more seats for less standing. These boosted demand for transit bus service, generating more revenues for municipalities. NABI changed the way municipalities saw their revenues and costs involved in transit bus service. NABI created exceptional value for the buyers in this case for both municipalities and end users at a low life-cycle cost.

FIGURE 3-3

The Strategy Canvas of the U.S. Municipal Bus Industry, Circa 2001

Not surprisingly, both municipalities and riders loved the new buses. NABI has captured 20 percent of the U.S. market since its inception in 1993, quickly vying for the number one slot in market share, growth, and profitability. NABI, based in Hungary, created a blue ocean that made the competition irrelevant in the United States, creating a win-win for all: itself, municipalities, and citizens. It has accumulated more than $1 billion in orders and was named by the Economist Intelligence Unit in October 2002 as one of the thirty most successful companies in the world.

Similarly, consider the British teakettle industry, which, despite its importance to British culture, had flat sales and shrinking profit margins until Philips Electronics came along with a teakettle that turned the red ocean blue. By thinking in terms of complementary products and services, Philips saw that the biggest issue the British had in brewing tea was not in the kettle itself but in the complementary product of water, which had to be boiled in the kettle. The issue was the lime scale found in tap water. The lime scale accumulated in kettles as the water was boiled, and later found its way into the freshly brewed tea. The phlegmatic British typically took a teaspoon and went fishing to capture the off-putting lime scale before drinking homebrewed tea. To the kettle industry, the water issue was not its problem. It was the problem of another industry the public water supply.

By thinking in terms of solving the major pain points in customers' total solution, Philips saw the water problem as its oppor tunity. The result: Philips created a kettle having a mouth filter that effectively captured the lime scale as the water was poured. Lime scale would never again be found swimming in British homebrewed tea. The industry was again kick-started on a strong growth trajectory as people began replacing their old kettles with the new filtered kettles.

There are many other examples of companies that have followed this path to create a blue ocean. Borders and Barnes & Noble (B&N) superstores redefined the scope of the services they offer. They transformed the product they sell from the book itself into the pleasure of reading and intellectual exploration, adding lounges, knowledgeable staff, and coffee bars to create an environment that celebrates reading and learning. In less than six years, Borders and B&N emerged as the two largest bookstore chains in the United States, with more than one thousand seventy superstores between them. Virgin Entertainment's megastores combine CDs, videos, computer games, and stereo and audio equipment to satisfy buyers' complete entertainment needs. Dyson designs its vacuum cleaners to eliminate the cost and annoyance of having to buy and change vacuum cleaner bags. Zeneca's Salick cancer centers combine all the cancer treatments their patients might need under one roof so that they don't have to go from one specialized center to another, making separate appointments for each service they require.

What is the context in which your product or service is used? What happens before, during, and after? Can you identify the pain points? How can you eliminate these pain points through a complementary product or service offering?

Path 5: Look Across Functional or Emotional Appeal to Buyers

Competition in an industry tends to converge not only on an accepted notion of the scope of its products and services but also on one of two possible bases of appeal. Some industries compete principally on price and function largely on calculations of utility; their appeal is rational. Other industries compete largely on feelings; their appeal is emotional.

Yet the appeal of most products or services is rarely intrinsically one or the other. Rather it is usually a result of the way companies have competed in the past, which has unconsciously educated consumers on what to expect. Companies' behavior affects buyers' expectations in a reinforcing cycle. Over time, functionally oriented industries become more functionally oriented; emotionally oriented industries become more emotionally oriented. No wonder market research rarely reveals new insights into what attracts customers. Industries have trained customers in what to expect. When surveyed, they echo back: more of the same for less.

When companies are willing to challenge the functionalemotional orientation of their industry, they often find new market space. We have observed two common patterns. Emotionally oriented industries offer many extras that add price without enhancing functionality. Stripping away those extras may create a fundamentally simpler, lower-priced, lower-cost business model that customers would welcome. Conversely, functionally oriented industries can often infuse commodity products with new life by adding a dose of emotion and, in so doing, can stimulate new demand.

Two well-known examples are Swatch, which transformed the functionally driven budget watch industry into an emotionally driven fashion statement, or The Body Shop, which did the reverse, transforming the emotionally driven industry of cosmetics into a functional, no-nonsense cosmetics house. In addition, consider the experience of QB (Quick Beauty) House. QB House created a blue ocean in the Japanese barbershop industry and is rapidly growing throughout Asia. Started in 1996 in Tokyo, QB House has blossomed from one outlet in 1996 to more than two hundred shops in 2003. The number of visitors surged from 57,000 in 1996 to 3.5 million annually in 2002. The company is expanding in Singapore and Malaysia and is targeting one thousand outlets in Asia by 2013.

At the heart of QB House's blue ocean strategy is a shift in the Asian barbershop industry from an emotional industry to a highly functional one. In Japan the time it takes to get a man's haircut hovers around one hour. Why? A long process of activities is undertaken to make the haircutting experience a ritual. Numerous hot towels are applied, shoulders are rubbed and massaged, customers are served tea and coffee, and the barber follows a ritual in cutting hair, including special hair and skin treatments such as blow drying and shaving. The result is that the actual time spent cutting hair is a fraction of the total time. Moreover, these actions create a long queue for other potential customers. The price of this haircutting process is 3,000 to 5,000 yen ($27 to $45).

QB House changed all that. It recognized that many people, especially working professionals, do not wish to waste an hour on a haircut. So QB House stripped away the emotional service elements of hot towels, shoulder rubs, and tea and coffee. It also dramatically reduced special hair treatments and focused mainly on basic cuts. QB House then went one step further, eliminating the traditional time-consuming wash-and-dry practice by creating the "air wash" system an overhead hose that is pulled down to "vacuum" every cut-off hair. This new system works much better and faster, without getting the customer's head wet. These changes reduced the haircutting time from one hour to ten minutes. Moreover, outside each shop is a traffic light system that indicates when a haircut slot is available. This removes waiting time uncertainty and eliminates the reservation desk.

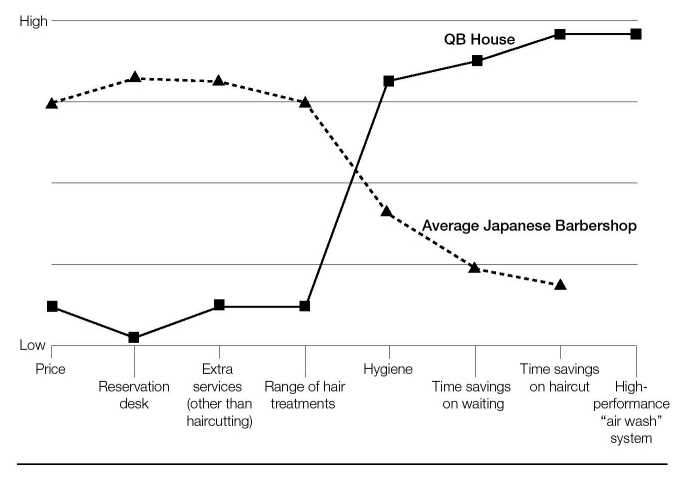

In this way, QB House was able to reduce the price of a haircut to 1,000 yen ($9) versus the industry average of 3,000 to 5,000 yen ($27-$45) while raising the hourly revenue earned per barber nearly 50 percent, with lower staff costs and less required retail space per barber. QB House created this "no-nonsense" haircutting service with improved hygiene. It introduced not only a sanitation facility set up for each chair but also a "one-use" policy, where every customer is provided with a new set of towel and comb. To appreciate its blue ocean creation, see figure 3-4.

Cemex, the world's third-largest cement producer, is another company that created a blue ocean by shifting the orientation of its industry this time in the reverse direction, from functional to emotional. In Mexico, cement sold in retail bags to the average do-it-yourselfer represents more than 85 percent of the total cement market.` As it stood, however, the market was unattractive. There were far more noncustomers than customers. Even though most poor families owned their own land and cement was sold as a relatively inexpensive functional input material, the Mexican population lived in chronic overcrowding. Few families built additions, and those that did took on average four to seven years to build only one additional room. Why? Most of the families' extra money was spent on village festivals, quinceaneras (girls' fifteen-year birthday parties), baptisms, and weddings. Contributing to these important milestone events was a chance to distinguish oneself in the community, whereas not contributing would be a sign of arrogance and disrespect.

FIGURE 3-4

The Strategy Canvas of QB House

As a result, most of Mexico's poor had insufficient and inconsistent savings to purchase building materials, even though having a cement house was the stuff of dreams in Mexico. Cemex conservatively estimated that this market could grow to be worth $500 million to $600 million annually if it could unlock this latent demand.5

Cemex's answer to this dilemma came in 1998 with its launch of the Patrimonio Hoy program, which shifted the orientation of cement from a functional product to the gift of dreams. When people bought cement they were on the path to building rooms of love, where laughter and happiness could be shared what better gift could there be? At the foundation of Patrimonio Hoy was the traditional Mexican system of tandas, a traditional community savings scheme. In a tanda, ten individuals (for example) contribute 100 pesos per week for ten weeks. In the first week, lots are drawn to see who "wins" the 1,000 pesos ($93) in each of the ten weeks. All participants win the 1,000 pesos one time only, but when they win, they receive a large amount to make a large purchase.

In traditional tandas the "winning" family would spend the windfall on an important festive or religious event such as a baptism or marriage. In the Patrimonio Hoy, however, the supertanda is directed toward building room additions with cement. Think of it as a form of wedding registry, except that instead of giving, for example, silverware, Cemex positioned cement as a loving gift.

The Patrimonio Hoy building materials club that Cemex set up consisted of a group of roughly seventy people contributing on average 120 pesos each week for seventy weeks. The winner of the supertanda each week, however, did not receive the total sum in pesos but rather received the equivalent building materials to complete an entire new room. Cemex complemented the winnings with the delivery of the cement to the winner's home, construction classes on how to effectively build rooms, and a technical adviser who maintained a relationship with the participants during their project.

Whereas Cemex's competitors sold bags of cement, Cemex was selling a dream, with a business model involving innovative financing and construction know-how. Cemex went a step further, throwing small festivities for the town when a room was finished and thereby reinforcing the happiness it brought to people and the tanda tradition.

Since the company launched this new emotional orientation of Cemex cement coupled with its funding and technical services, demand for cement has soared. Around 20 percent more families are building additional rooms, and families are planning to build two to three more rooms than originally planned. In a market that competed on price with slow growth, Cemex enjoys 15 percent monthly growth, selling its cement at higher prices (roughly 3.5 pesos). Cemex has so far tripled cement consumption by the mass of do-it-yourself homebuilders-from 2,300 pounds consumed every four years, on average, to the same amount being consumed in fifteen months. The predictability of the quantities of cement sold through the supertandas also drops Cemex's cost structure via lower inventory costs, smoother production runs, and guaranteed sales that lower costs of capital. Social pressure makes defaults on supertanda payments rare. Overall, Cemex created a blue ocean of emotional cement that achieved differentiation at a low cost.

Similarly, with its wildly successful Viagra, Pfizer shifted the focus from medical treatment to lifestyle enhancement. Likewise, consider how Starbucks turned the coffee industry on its head by shifting its focus from commodity coffee sales to the emotional atmosphere in which customers enjoy their coffee.

A burst of blue ocean creation is under way in a number of service industries but in the opposite direction moving from an emotional to a functional orientation. Relationship businesses, such as insurance, banking, and investing, have relied heavily on the emotional bond between broker and client. They are ripe for change. Direct Line Group, a U.K. insurance company, for example, has done away with traditional brokers. It reasoned that customers would not need the hand-holding and emotional comfort that brokers traditionally provide if the company did a better job of, for example, paying claims rapidly and eliminating complicated paperwork. So instead of using brokers and regional branch offices, Direct Line uses information technology to improve claims handling, and it passes on some of the cost savings to customers in the form of lower insurance premiums. In the United States, The Vanguard Group (in index funds) and Charles Schwab (in brokerage services) are doing the same thing in the investment industry, creating a blue ocean by transforming emotionally oriented businesses based on personal relationships into high-performance, low-cost functional businesses.

Does your industry compete on functionality or emotional appeal? If you compete on emotional appeal, what elements can you strip out to make it functional? If you compete on functionality, what elements can be added to make it emotional?

Path 6: Look Across Time

All industries are subject to external trends that affect their businesses over time. Think of the rapid rise of the Internet or the global movement toward protecting the environment. Looking at these trends with the right perspective can show you how to create blue ocean opportunities.

Most companies adapt incrementally and somewhat passively as events unfold. Whether it's the emergence of new technologies or major regulatory changes, managers tend to focus on projecting the trend itself. That is, they ask in which direction a technology will evolve, how it will be adopted, whether it will become scalable. They pace their own actions to keep up with the development of the trends they're tracking.

But key insights into blue ocean strategy rarely come from projecting the trend itself. Instead they arise from business insights into how the trend will change value to customers and impact the company's business model. By looking across time from the value a market delivers today to the value it might deliver tomorrow managers can actively shape their future and lay claim to a new blue ocean. Looking across time is perhaps more difficult than the previous approaches we've discussed, but it can be made subject to the same disciplined approach. We're not talking about predicting the future, something that is inherently impossible. Rather, we're talking about finding insight in trends that are observable today.

Three principles are critical to assessing trends across time. To form the basis of a blue ocean strategy, these trends must be decisive to your business, they must be irreversible, and they must have a clear trajectory. Many trends can be observed at any one time for example, a discontinuity in technology, the rise of a new lifestyle, or a change in regulatory or social environments. But usually only one or two will have a decisive impact on any particular business. And it may be possible to see a trend or major event without being able to predict its direction.

In 1998, for example, the mounting Asian crisis was an important trend certain to have a big impact on financial services. But it was impossible to predict the direction that trend would take, and therefore it would have been a risky enterprise to envision a blue ocean strategy that might result from it. In contrast, the euro has been evolving along a constant trajectory as it has been replacing Europe's multiple currencies. It is a decisive, irreversible, and clearly developing trend in financial services upon which blue oceans can be created as the European Union continues to enlarge.

Having identified a trend of this nature, you can then look across time and ask yourself what the market would look like if the trend were taken to its logical conclusion. Working back from that vision of a blue ocean strategy, you can identify what must be changed today to unlock a new blue ocean.

For example, Apple observed the flood of illegal music file sharing that began in the late 1990s. Music file sharing programs such as Napster, Kazaa, and Lime Wire had created a network of Internetsavvy music lovers freely, yet illegally, sharing music across the globe. By 2003 more than two billion illegal music files were being traded every month. While the recording industry fought to stop the cannibalization of physical CDs, illegal digital music downloading continued to grow.

With the technology out there for anyone to digitally download music free instead of paying $19 for an average CD, the trend toward digital music was clear. This trend was underscored by the fastgrowing demand for MP3 players that played mobile digital music, such as Apple's hit iPod. Apple capitalized on this decisive trend with a clear trajectory by launching the iTunes online music store in 2003.

In agreement with five major music companies BMG, EMI Group, Sony, Universal Music Group, and Warner Brothers Records iTunes offered legal, easy-to-use, and flexible a la carte song downloads. iTunes allowed buyers to freely browse two hundred thousand songs, listen to thirty-second samples, and download an individual song for 99 cents or an entire album for $9.99. By allowing people to buy individual songs and strategically pricing them far more reasonably, iTunes broke a key customer annoyance factor: the need to purchase an entire CD when they wanted only one or two songs on it.

iTunes also leapt past free downloading services, providing sound quality as well as intuitive navigating, searching, and browsing functions. To illegally download music you must first search for the song, album, or artist. If you are looking for a complete album you must know the names of all the songs and their order. It is rare to find a complete album to download in one location. The sound quality is consistently poor because most people burn CDs at a low bit rate to save space. And most of the tracks available reflect the tastes of sixteen-year-olds, so although theoretically there are billions of tracks available, the scope is limited.

In contrast, Apple's search and browsing functions are considered the best in the business. Moreover, iTunes music editors include a number of added features usually found in the record shops, including iTunes essentials such as Best Hair Bands or Best Love Songs, staff favorites, celebrity play lists, and Billboard charts. And the iTunes sound quality is the highest because iTunes encodes songs in a format called AAC, which offers sound quality superior to MP3s, even those burned at a very high data rate.

Customers have been flocking to iTunes, and recording companies and artists are also winning. Under iTunes they receive 65 percent of the purchase price of digitally downloaded songs, at last financially benefiting from the digital downloading craze. In addition, Apple further protected recording companies by devising copyright protection that would not inconvenience users who had grown accustomed to the freedom of digital music in the postNapster world but would satisfy the music industry. The iTunes Music Store allows users to burn songs onto iPods and CDs up to seven times, enough to easily satisfy music lovers but far too few times to make professional piracy an issue.

Today the iTunes Music Store offers more than 700,000 songs and has sold more than 70 million songs in its first year, with users downloading on average 2.5 million per week. Nielsen//NetRatings estimates that the iTunes Music Store now accounts for 70 percent of the legal music download market. Apple's iTunes is unlocking a blue ocean in digital music, with the added advantage of increasing the attractiveness of its already hot iPod player. As other online music stores enter the fray, the challenge for Apple will be to keep its sights on the evolving mass market and not to fall into competitive benchmarking or high-end niche marketing.

Similarly, Cisco Systems created a new market space by thinking across time trends. It started with a decisive and irreversible trend that had a clear trajectory: the growing demand for high-speed data exchange. Cisco looked at the world as it was and concluded that the world was hampered by slow data rates and incompatible computer networks. Demand was exploding as, among other factors, the number of Internet users doubled roughly every one hundred days. So Cisco could clearly see that the problem would inevitably worsen. Cisco's routers, switches, and other networking devices were designed to create breakthrough value for customers, offering fast data exchanges in a seamless networking environment. Thus Cisco's insight is as much about value innovation as it is about technology. Today more than 80 percent of all traffic on the Internet goes through Cisco's products, and its gross margins in this new market space have been in the 60 percent range.

Similarly, a host of other companies are creating blue oceans by applying path 6. Consider how CNN created the first real-time twenty-four-hour global news network based on the rising tide of globalization. Or how HBO's hit show Sex and the City acted on the trend of increasingly urban and successful women who struggle to find love and marry later in life.

What trends have a high probability of impacting your industry, are irreversible, and are evolving in a clear trajectory? How will these trends impact your industry? Given this, how can you open up unprecedented customer utility?

Conceiving New Market Space

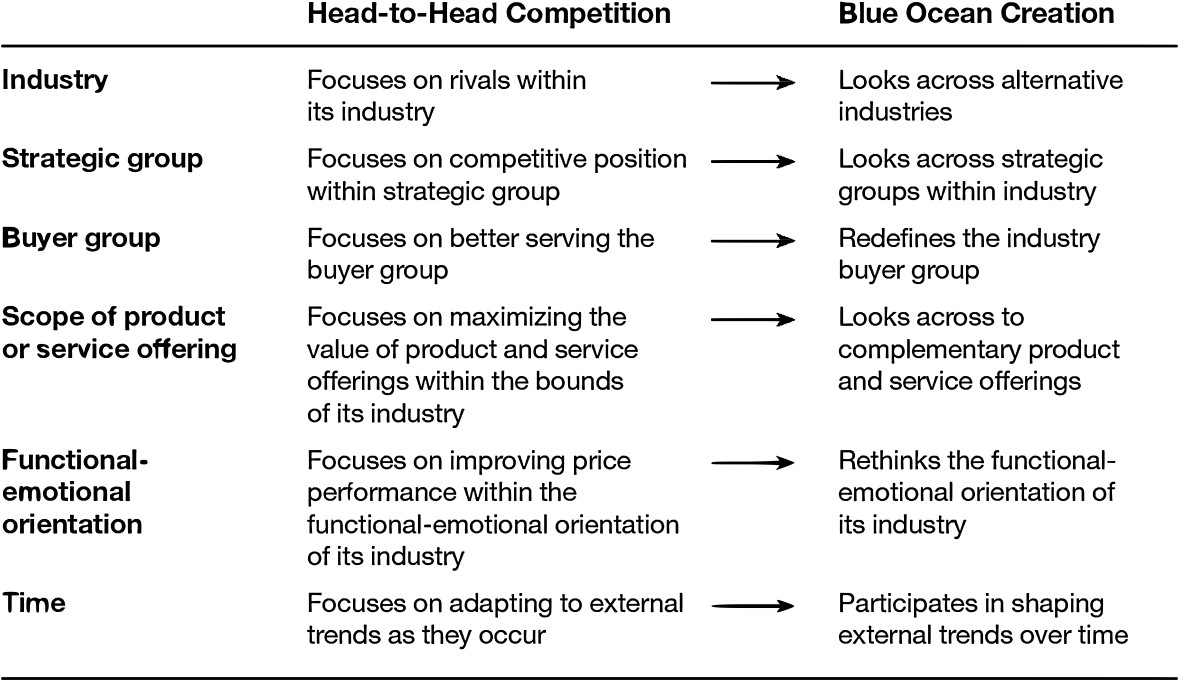

By thinking across conventional boundaries of competition, you can see how to make convention-altering, strategic moves that reconstruct established market boundaries and create blue oceans. The process of discovering and creating blue oceans is not about predicting or preempting industry trends. Nor is it a trial-and-error process of implementing wild new business ideas that happen to come across managers' minds or intuition. Rather, managers are engaged in a structured process of reordering market realities in a fundamentally new way. Through reconstructing existing market elements across industry and market boundaries, they will be able to free themselves from head-to-head competition in the red ocean. Figure 3-5 summarizes the six-path framework.

FIGURE 3-5

From Head-to-Head Competition to Blue Ocean Creation

We are now ready to move on to building your strategy planning process around these six paths. We next look at how you reframe your strategy planning process to focus on the big picture and apply these ideas in formulating your own blue ocean strategy.