Build Execution into Strategy

COMPANY IS NOT ONLY TOP MANAGEMENT, nor is Lit only middle management. A company is everyone from the top to the front lines. And it is only when all the members of an organization are aligned around a strategy and support it, for better or for worse, that a company stands apart as a great and consistent executor. Overcoming the organizational hurdles to strategy execution is an important step toward that end. It removes the roadblocks that can put a halt to even the best of strategies.

COMPANY IS NOT ONLY TOP MANAGEMENT, nor is Lit only middle management. A company is everyone from the top to the front lines. And it is only when all the members of an organization are aligned around a strategy and support it, for better or for worse, that a company stands apart as a great and consistent executor. Overcoming the organizational hurdles to strategy execution is an important step toward that end. It removes the roadblocks that can put a halt to even the best of strategies.

But in the end, a company needs to invoke the most fundamental base of action: the attitudes and behavior of its people deep in the organization. You must create a culture of trust and commitment that motivates people to execute the agreed strategy not to the letter, but to the spirit. People's minds and hearts must align with the new strategy so that at the level of the individual, people embrace it of their own accord and willingly go beyond compulsory execution to voluntary cooperation in carrying it out.

Where blue ocean strategy is concerned, this challenge is heightened. Trepidation builds as people are required to step out of their comfort zones and change how they have worked in the past. They wonder, What are the real reasons for this change? Is top management honest when it speaks of building future growth through a change in strategic course? Or are they trying to make us redundant and work us out of our jobs?

The more removed people are from the top and the less they have been involved in the creation of the strategy, the more this trepidation builds. On the front line, at the very level at which a strategy must be executed day in and day out, people can resent having a strategy thrust upon them with little regard for what they think and feel. Just when you think you have done everything right, things can suddenly go very wrong in your front line.

This brings us to the sixth principle of blue ocean strategy: To build people's trust and commitment deep in the ranks and inspire their voluntary cooperation, companies need to build execution into strategy from the start. That principle allows companies to minimize the management risk of distrust, noncooperation, and even sabotage. This management risk is relevant to strategy execution in both red and blue oceans, but it is greater for blue ocean strategy because its execution often requires significant change. Hence, minimizing such risk is essential as companies execute blue ocean strategy. Companies must reach beyond the usual suspects of carrots and sticks. They must reach to fair process in the making and executing of strategy.

Our research shows that fair process is a key variable that distinguishes successful blue ocean strategic moves from those that failed. The presence or absence of fair process can make or break a company's best execution efforts.

Poor Process Can Ruin Strategy Execution

Consider the experience of a global leader in supplying waterbased liquid coolants for metalworking industries. We'll call this organization Lubber. Because of the many processing parameters in metal-based manufacturing, there are several hundred complex types of coolants to choose from. Choosing the right coolant is a delicate process. Products must first be tested on production machines before purchasing, and the decision often rests on fuzzy logic. The result is machine downtime and sampling costs, and these are expensive for customers and Lubber alike.

To offer customers a leap in value, Lubber devised a strategy to eliminate the complexity and costs of the trial phase. Using artificial intelligence, it developed an expert system that cut the failure rate in selecting coolants to less than 10 percent from an industry average of 50 percent. The system also reduced machine downtime, eased coolant management, and raised the overall quality of work pieces produced. As for Lubber, the sales process was dramatically simplified, giving sales representatives more time to gain new sales and dropping the costs per sale.

This win-win value innovation strategic move, however, was doomed from the start. It wasn't that the strategy was not good or that the expert system did not work; it worked exceptionally well. The strategy was doomed because the sales force fought it.

Having not been engaged in the strategymaking process nor apprised of the rationale for the strategic shift, sales reps saw the expert system in a light no one on the design team or management team had ever imagined. To them, it was a direct threat to what they saw as their most valuable contribution tinkering in the trial phase to find the right waterbased coolant from the long list of possible candidates. All the wonderful benefits having a way to avoid the hassle-filled part of their job, having more time to pull in more sales, and winning more contracts by standing out in the industrywent unappreciated.

With the sales force feeling threatened and often working against the expert system by expressing doubts about its effectiveness to customers, sales did not take off. After cursing its hubris and learning the hard way the importance of dealing with managerial risk up front based on the proper process, management was forced to pull the expert system from the market and work on rebuilding trust with its sales representatives.

The Power of Fair Process

What, then, is fair process? And how does it allow companies to build execution into strategy? The theme of fairness or justice has preoccupied writers and philosophers throughout the ages. But the direct theoretical origin of fair process traces back to two social scientists: John W. Thibaut and Laurens Walker. In the mid-1970s, they combined their interest in the psychology of justice with the study of process, creating the term procedural justice.' Focusing their attention on legal settings, they sought to understand what makes people trust a legal system so that they will comply with laws without being coerced. Their research established that people care as much about the justice of the process through which an outcome is produced as they do about the outcome itself. People's satisfaction with the outcome and their commitment to it rose when procedural justice was exercised.2

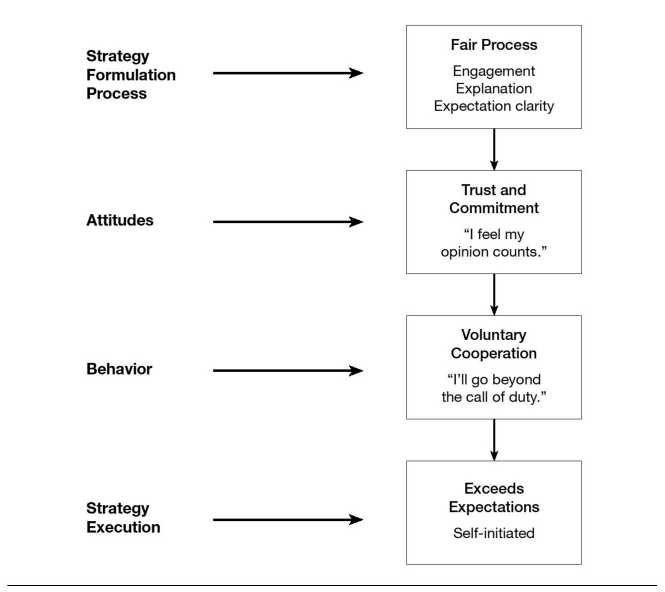

FIGURE 8-1

How Fair Process Affects People's Attitudes and Behavior

Fair process is our managerial expression of procedural justice theory. As in legal settings, fair process builds execution into strategy by creating people's buy-in up front. When fair process is exercised in the strategymaking process, people trust that a level playing field exists. This inspires them to cooperate voluntarily in executing the resulting strategic decisions.

Voluntary cooperation is more than mechanical execution, where people do only what it takes to get by. It involves going beyond the call of duty, wherein individuals exert energy and initiative to the best of their abilities even subordinating personal self-interest to execute resulting strategies.3 Figure 8-1 presents the causal flow we observed among fair process, attitudes, and behavior.

The Three E Principles of Fair Process

There are three mutually reinforcing elements that define fair process: engagement, explanation, and clarity of expectation. Whether people are senior executives or shop floor employees, they all look to these elements. We call them the three E principles of fair process.

Engagement means involving individuals in the strategic decisions that affect them by asking for their input and allowing them to refute the merits of one another's ideas and assumptions. Engagement communicates management's respect for individuals and their ideas. Encouraging refutation sharpens everyone's thinking and builds better collective wisdom. Engagement results in better strategic decisions by management and greater commitment from all involved to execute those decisions.

Explanation means that everyone involved and affected should understand why final strategic decisions are made as they are. An explanation of the thinking that underlies decisions makes people confident that managers have considered their opinions and have made decisions impartially in the overall interests of the company. An explanation allows employees to trust managers' intentions even if their own ideas have been rejected. It also serves as a powerful feedback loop that enhances learning.

Expectation clarity requires that after a strategy is set, managers state clearly the new rules of the game. Although the expectations may be demanding, employees should know up front what standards they will be judged by and the penalties for failure. What are the goals of the new strategy? What are the new targets and milestones? Who is responsible for what? To achieve fair process, it matters less what the new goals, expectations, and responsibilities are and more that they are clearly understood. When people clearly understand what is expected of them, political jockeying and favoritism are minimized, and people can focus on executing the strategy rapidly.

Taken together, these three criteria collectively lead to judgments of fair process. This is important, because any subset of the three does not create judgments of fair process.

A Tale of Two Plants

How do the three E principles of fair process work to affect strategy execution deep in an organization? Consider the experience of an elevator systems manufacturer we'll call Elco. In the late 1980s, sales in the elevator industry declined. Excess office space left some large U.S. cities with vacancy rates as high as 20 percent.

With domestic demand falling, Elco set out to offer buyers a leap in value while lowering its costs to stimulate new demand and break from the competition. In its quest to create and execute a blue ocean strategy, the company realized that it needed to replace its batch-manufacturing system with a cellular approach that would allow self-directed teams to achieve superior performance. The management team was in agreement and ready to go. To exe cute this key element of its strategy, the team adopted what looked like the fastest and smartest way to move forward.

It would first install the new system at Elco's Chester plant and then roll it out to its second plant, High Park. The logic was simple. The Chester plant had exemplary employee relations, so much so that the workers had decertified their own union. Management was certain it could count on employee cooperation to execute the strategic shift in manufacturing. In the company's words, "They were the ideal work force." Next, Elco would roll out the process to its plant in High Park, where a strong union was expected to resist that, or any other, change. Management was counting on having achieved a degree of momentum for execution at Chester that it hoped would have positive spillover effects on High Park.

The theory was good. In practice, however, things took an unpredicted turn. The introduction of the new manufacturing process at the Chester plant quickly led to disorder and rebellion. Within a few months, both cost and quality performance were in free fall. Employees were talking about bringing back the union. Having lost control, the despairing plant manager called Elco's industrial psychologist for help.

In contrast, the High Park plant, despite its reputation for resistance, had accepted the strategic shift in the manufacturing process. Every day, the High Park manager waited for the anticipated meltdown, but it never came. Even when people didn't like the decisions, they felt they had been treated fairly, and so they willingly participated in the rapid execution of the new manufacturing process, a pivotal component of the company's new strategy.

A closer look at the way the strategic shift was made at the two plants reveals the reasons behind this apparent anomaly. At the Chester plant, Elco managers violated all three of the basic principles of fair process. First, they failed to engage employees in the strategic decisions that directly affected them. Lacking expertise in cellular manufacturing, Elco brought in a consulting firm to design a master plan for the conversion. The consultants were briefed to work quickly and with minimal disturbance to employees so that fast, painless implementation could be achieved. The consultants followed the instructions. When Chester employees arrived at work they discovered strangers at the plant who not only dressed differently wearing dark suits, white shirts, and ties but also spoke in low tones to one another. To minimize disturbance, they didn't interact with employees. Instead they quietly hovered behind people's backs, taking notes and drawing diagrams. The rumor circulated that after employees went home in the afternoon, these same people would swarm across the plant floor, snoop around people's workstations, and have heated discussions.

During this period, the plant manager was increasingly absent. He was spending more time at Elco's head office in meetings with the consultants sessions deliberately scheduled away from the plant so as not to distract the employees. But the plant manager's absence produced the opposite effect. As people grew anxious, wondering why the captain of their ship seemed to be deserting them, the rumor mill moved into high gear. Everyone became convinced that the consultants would downsize the plant. They were sure they were about to lose their jobs. The fact that the plant manager was always gone without any explanation obviously, he was avoiding them could only mean that management was, they thought, "trying to put one over on us." Trust and commitment at the Chester plant deteriorated quickly.

Soon, people were bringing in newspaper clippings about other plants around the country that had been shut down with the help of consultants. Employees saw themselves as imminent victims of management's hidden intention to downsize and work people out of their jobs. In fact, Elco managers had no intention of closing the plant. They wanted to cut waste, freeing people to produce higher-quality elevators faster at lower cost to leapfrog the competition. But plant employees could not have known that.

Managers at Chester also didn't explain why strategic decisions were being made the way they were and what those decisions meant to employees' careers and work methods. Management unveiled the master plan for change in a thirty-minute session with employees. The audience heard that their time-honored way of working would be abolished and replaced by something called "cellular manufacturing." No one explained why the strategic shift was needed, how the company needed to break away from the competition to stimulate new demand, and why the shift in the manufacturing process was a key element of that strategy. Employees sat in stunned silence, with no understanding of the rationale behind the change. The managers mistook this for acceptance, forgetting how long it had taken them over the preceding few months to get comfortable with the idea of shifting to cellular manufacturing to execute the new strategy.

Master plan in hand, management quickly began rearranging the plant. When employees asked what the new layout aimed to achieve, the response was "efficiency gains." The managers didn't have time to explain why efficiency had to be improved and didn't want to worry employees. But lacking an intellectual understanding of what was happening to them, some employees began feeling sick as they came to work.

Managers also neglected to make clear what would be expected of employees under the new manufacturing process. They informed employees that they would no longer be judged on individual performance but rather on the performance of the cell. They said that faster or more experienced employees would have to pick up the slack for slower or less experienced colleagues. But they didn't elaborate. How the new cellular system was supposed to work, managers didn't make clear.

Violations of the principles of fair process undermined employees' trust in the strategic shift and in management. In fact, the new cell design offered tremendous benefits to employees for example, making vacations easier to schedule and giving them the opportunity to broaden their skills and engage in a greater variety of work. Yet employees could see only its negative side. They began taking out their fear and anger on one another. Fights erupted on the plant floor as employees refused to help those they called "lazy people who can't finish their own jobs" or interpreted offers of help as meddling, responding with, "This is my job. You keep to your own workstation."

Chester's model work force was falling apart. For the first time in the plant manager's career, employees refused to do as they were asked, turning down assignments "even if you fire me." They felt they could no longer trust the once popular plant manager, so they began to go around him, taking their complaints directly to his boss at the head office. In the absence of fair process, the Chester plant's employees rejected the transformation and refused to play their role in executing the new strategy.

In contrast, management at the High Park plant abided by all three principles of fair process when introducing the strategic shift. When the consultants came to the plant, the plant manager introduced them to all employees. Management engaged employees by holding a series of plantwide meetings, where corporate executives openly discussed the declining business conditions and the company's need for a change in strategic course to break from the competition and simultaneously achieve higher value at lower cost. They explained that they had visited other companies' plants and had seen the productivity improvements that cellular manufacturing could bring. They explained how this would be a pivotal determinant of the company's ability to achieve its new strategy. They announced a proaction-time policy to calm employees' justifiable fears of layoffs. As old performance measures were discarded, managers worked with employees to develop new ones and to establish each cell team's new responsibilities. Goals and expectations were made clear to employees.

By practicing the three principles of fair process in tandem, management won the understanding and support of High Park employees. The employees spoke of their plant manager with admiration, and they commiserated with the difficulties Elco's managers had in executing the new strategy and making the changeover to cellular manufacturing. They concluded that it had been a necessary, worthwhile, and positive experience.

Elco's managers still regard this experience as one of the most painful in their careers. They learned that people in the front line care as much about the proper process as those at the top. By violating fair process in making and rolling out strategies, managers can turn their best employees into their worst, earning their distrust of and resistance to the very strategy they depend on them to execute. But if managers practice fair process, the worst employees can turn into the best and can execute even difficult strategic shifts with their willing commitment while building their trust.

Why Does Fair Process Matter?

Why is fair process important in shaping people's attitudes and behavior? Specifically, why does the observance or violation of fair process in strategy making have the power to make or break a strategy's execution? It all comes down to intellectual and emotional recognition.

Emotionally, individuals seek recognition of their value, not as "labor," "personnel," or "human resources" but as human beings who are treated with full respect and dignity and appreciated for their individual worth regardless of hierarchical level. Intellectually, individuals seek recognition that their ideas are sought after and given thoughtful reflection, and that others think enough of their intelligence to explain their thinking to them. Such frequently cited expressions in our interviews as "that goes for everyone I know" or "every person wants to feel" and constant references to "people" and "human beings" reinforce the point that managers must see the nearly universal value of the intellectual and emotional recognition that fair process conveys.

Intellectual and Emotional Recognition Theory

Using fair process in strategy making is strongly linked to both intellectual and emotional recognition. It proves through action that there is an eagerness to trust and cherish the individual as well as a deep-seated confidence in the individual's knowledge, talents, and expertise.

When individuals feel recognized for their intellectual worth, they are willing to share their knowledge; in fact, they feel inspired to impress and confirm the expectation of their intellectual value, suggesting active ideas and knowledge sharing. Similarly, when individuals are treated with emotional recognition, they feel emotionally tied to the strategy and inspired to give their all. Indeed, in Frederick Herzberg's classic study on motivation, recognition was found to inspire strong intrinsic motivation, causing people to go beyond the call of duty and engage in voluntary cooperation.4 Hence, to the extent that fair process judgments convey intellectual and emotional recognition, people will better apply their knowledge and expertise, as well as their voluntary efforts to cooperate for the organization's success in executing strategy.

However, there is a flip side to this that is deserving of equal, if not more, attention: the violation of fair process and, with it, the violation of recognizing individuals' intellectual and emotional worth. The observed pattern of thought and behavior can be summarized as follows. If individuals are not treated as though their knowledge is valued, they will feel intellectual indignation and will not share their ideas and expertise; rather, they will hoard their best thinking and creative ideas, preventing new insights from seeing the light of day. What's more, they will reject others' intellectual worth as well. It's as if they were saying, "You don't value my ideas. So I don't value your ideas, nor do I trust in or care about the strategic decisions you've reached."

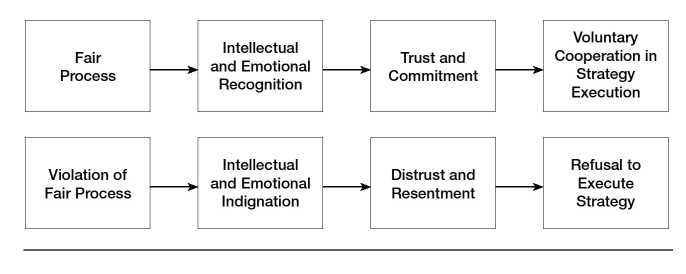

Similarly, to the extent that people's emotional worth is not recognized, they will feel angry and will not invest their energy in their actions; rather, they will drag their feet and apply counterefforts, including sabotage, as in the case of Elco's Chester plant. This often leads employees to push for rolling back strategies that have been imposed unfairly, even when the strategies themselves were good ones critical to the company's success or beneficial to employees and managers themselves. Lacking trust in the strategymaking process, people lack trust in the resulting strategies. Such is the emotional power that fair process can provoke. Figure 8-2 shows the observed causal pattern.

FIGURE 8-2

The Execution Consequences of the Presence and Absence of Fair Process in Strategy Making

Fair Process and Blue Ocean Strategy

Commitment, trust, and voluntary cooperation are not merely attitudes or behaviors. They are intangible capital. When people have trust, they have heightened confidence in one another's intentions and actions. When they have commitment, they are even willing to override personal self-interest in the interests of the company.

If you ask any company that has created and successfully executed a blue ocean strategy, managers will be quick to rattle off how important this intangible capital is to their success. Similarly, managers from companies that have failed in executing blue ocean strategies will point out that the lack of this capital contributed to their failure. These companies were not able to orchestrate strategic shifts because they lacked people's trust and commitment. Commitment, trust, and voluntary cooperation allow companies to stand apart in the speed, quality, and consistency of their execution and to implement strategic shifts fast at low cost.

The question companies wrestle with is how to create trust, commitment, and voluntary cooperation deep in the organization. You don't do it by separating strategy formulation from execution. Although this disconnect may be a hallmark of most companies' practice, it is also a hallmark of slow and questionable implementation, and mechanical follow-through at best. Of course, traditional incentives of power and money carrots and sticks help. But they fall short of inspiring human behavior that goes beyond outcomedriven self-interest. Where behavior cannot be monitored with certainty, there is still plenty of room for foot-dragging and sabotage.

The exercise of fair process gets around this dilemma. By organizing the strategy formulation process around the principles of fair process, you can build execution into strategy making from the start. With fair process, people tend to be committed to support the resulting strategy even when it is viewed as not favorable or at odds with their perception of what is strategically correct for their unit. People realize that compromises and sacrifices are necessary in building a strong company. They accept the need for short-term personal sacrifices in order to advance the long-term interests of the corporation. This acceptance is conditional, however, on the presence of fair process. Whatever the context in which a company's blue ocean strategy is executed be it working with a joint venture partner to outsource component manufacturing, reorienting the sales force, transforming the manufacturing process, relocating a company's call center from the United States to India we have consistently observed this dynamic at work.