Reach Beyond Existing Demand

O COMPANY WANTS to venture beyond red oceans only to find itself in a puddle. The question is, How do you maximize the size of the blue ocean you are creating? This brings us to the third principle of blue ocean strategy: Reach beyond existing demand. This is a key component of achieving value innovation. By aggregating the greatest demand for a new offering, this approach attenuates the scale risk associated with creating a new market.

O COMPANY WANTS to venture beyond red oceans only to find itself in a puddle. The question is, How do you maximize the size of the blue ocean you are creating? This brings us to the third principle of blue ocean strategy: Reach beyond existing demand. This is a key component of achieving value innovation. By aggregating the greatest demand for a new offering, this approach attenuates the scale risk associated with creating a new market.

To achieve this, companies should challenge two conventional strategy practices. One is the focus on existing customers. The other is the drive for finer segmentation to accommodate buyer differences. Typically, to grow their share of a market, companies strive to retain and expand existing customers. This often leads to finer segmentation and greater tailoring of offerings to better meet customer preferences. The more intense the competition is, the greater, on average, is the resulting customization of offerings. As companies compete to embrace customer preferences through finer segmentation, they often risk creating too-small target markets.

To maximize the size of their blue oceans, companies need to take a reverse course. Instead of concentrating on customers, they need to look to noncustomers. And instead of focusing on customer differences, they need to build on powerful commonalities in what buyers value. That allows companies to reach beyond existing demand to unlock a new mass of customers that did not exist before.

Think of Callaway Golf. It aggregated new demand for its offering by looking to noncustomers. While the U.S. golf industry fought to win a greater share of existing customers, Callaway created a blue ocean of new demand by asking why sports enthusiasts and people in the country club set had not taken up golf as a sport. By looking to why people shied away from golf, it found one key commonality uniting the mass of noncustomers: Hitting the golf ball was perceived as too difficult. The small size of the golf club head demanded enormous hand-eye coordination, took time to master, and required concentration. As a result, fun was sapped for novices, and it took too long to get good at the sport.

This understanding gave Callaway insight into how to aggregate new demand for its offering. The answer was Big Bertha, a golf club with a large head that made it far easier to hit the golf ball. Big Bertha not only converted noncustomers of the industry into customers, but it also pleased existing golf customers, making it a runaway bestseller across the board. With the exception of pros, it turned out that the mass of existing customers also had been frustrated with the difficulty of advancing their game by mastering the skills needed to hit the ball consistently. The club's large head also lessened this difficulty.

Interestingly, however, existing customers, unlike noncustomers, had implicitly accepted the difficulty of the game. Although the mass of existing customers didn't like it, they had taken for granted that that was the way the game was played. Instead of registering their dissatisfaction with golf club makers, they themselves accepted the responsibility to improve. By looking to noncustomers and focusing on their key commonalities not differences-Call away saw how to aggregate new demand and offer the mass of customers and noncustomers a leap in value.

Where is your locus of attention on capturing a greater share of existing customers, or on converting noncustomers of the industry into new demand? Do you seek out key commonalities in what buyers value, or do you strive to embrace customer differences through finer customization and segmentation? To reach beyond existing demand, think noncustomers before customers; commonalities before differences; and desegmentation before pursuing finer segmentation.

The Three Tiers of Noncustomers

Although the universe of noncustomers typically offers big blue ocean opportunities, few companies have keen insight into who noncustomers are and how to unlock them. To convert this huge latent demand into real demand in the form of thriving new customers, companies need to deepen their understanding of the universe of noncustomers.

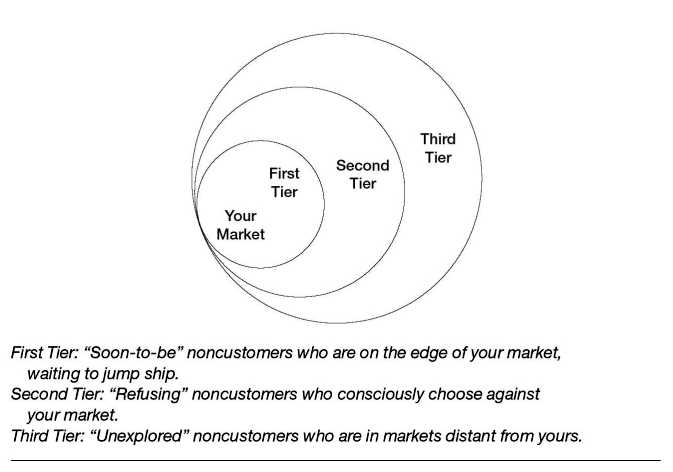

There are three tiers of noncustomers that can be transformed into customers. They differ in their relative distance from your market. As depicted in figure 5-1, the first tier of noncustomers is closest to your market. They sit on the edge of the market. They are buyers who minimally purchase an industry's offering out of necessity but are mentally noncustomers of the industry. They are waiting to jump ship and leave the industry as soon as the opportunity presents itself. However, if offered a leap in value, not only would they stay, but also their frequency of purchases would multiply, unlocking enormous latent demand.

The second tier of noncustomers is people who refuse to use your industry's offerings. These are buyers who have seen your industry's offerings as an option to fulfill their needs but have voted against them. In the Callaway case, for example, these were sports enthusiasts, especially the country club tennis set, who could have chosen golf but had consciously chosen against it.

FIGURE 5-1

The Three Tiers of Noncustomers

The third tier of noncustomers is farthest from your market. They are noncustomers who have never thought of your market's offerings as an option. By focusing on key commonalities across these noncustomers and existing customers, companies can understand how to pull them into their new market.

Let's look at each of the three tiers of noncustomers to understand how you can attract them and expand your blue ocean.

FirstTier Noncustomers

These soon-to-be noncustomers are those who minimally use the current market offerings to get by as they search for something better. Upon finding any better alternative, they will eagerly jump ship. In this sense, they sit on the edge of the market. A market be comes stagnant and develops a growth problem as the number of soon-to-be noncustomers increases. Yet locked within these firsttier noncustomers is an ocean of untapped demand waiting to be released.

Consider how Pret A Manger, a British fast-food chain that opened in 1988, has expanded its blue ocean by tapping into the huge latent demand of firsttier noncustomers. Before Pret, professionals in European city centers principally frequented restaurants for lunch. Sit-down restaurants offered a nice meal and setting. However, the number of firsttier noncustomers was high and rising. Growing concerns over the need for healthy eating gave people second thoughts about eating out in restaurants. And professionals did not always have time for a sit-down meal. Some restaurants were also too expensive for lunch on a daily basis. So professionals were increasingly grabbing something on the run, bringing a brown bag from home, or even skipping lunch.

These firsttier noncustomers were in search of better solutions. Although there were numerous differences across them, they shared three key commonalities: They wanted lunch fast, they wanted it fresh and healthy, and they wanted it at a reasonable price.

The insight gained from the commonalities across these firsttier noncustomers shed light on how Pret could unlock and aggregate untapped demand. The Pret formula is simple. It offers restaurantquality sandwiches made fresh every day from only the finest ingredients, and it makes the food available at a speed that is faster than that of restaurants and even fast food. It also delivers this in a sleek setting at reasonable prices.

Consider what Pret is like. Walking into a Pret A Manger is like walking into a bright Art Deco studio. Along the walls are clean refrigerated shelves stocked with more than thirty types of sandwiches (average price $4-$6) made fresh that day, in that shop, from fresh ingredients delivered earlier that morning. People can also choose from other freshly made items, such as salads, yogurt, parfaits, blended juices, and sushi. Each store has its own kitchen, and nonfresh items are made by high-quality producers. Even in its New York stores, Pret's baguettes are from Paris, its croissants are from Belgium, and its Danish pastries are from Denmark. And nothing is kept over to the next day. Leftover food is given to homeless shelters.

In addition to offering fresh healthy sandwiches and other fresh food items, Pret speeds up the customer ordering experience from fast food's queue-order-pay-wait-receive-sit down purchasing cycle to a much faster browse-pick up-pay-leave cycle. On average, customers spend just ninety seconds from the time they get in line to the time they leave the shop. This is made possible because Pret produces ready-made sandwiches and other things at high volume with a high standardization of assembly, does not make to order, and does not serve its customers. They serve themselves as in a supermarket.

Whereas sit-down restaurants have seen stagnant demand, Pret has been converting the mass of soon-to-be noncustomers into core thriving customers who eat at Pret more often than they used to eat at restaurants. Beyond this, as with Callaway, restaurant-goers who were content to eat lunch at restaurants also have been flocking to Pret. Although restaurant lunches had been acceptable, the three key commonalities of firsttier noncustomers struck a chord with these people; but unlike soon-to-be noncustomers, they had not thought to question their lunch habits. The lesson: Noncustomers tend to offer far more insight into how to unlock and grow a blue ocean than do relatively content existing customers.

Today Pret A Manger sells more than twenty-five million sandwiches a year from its one hundred thirty stores in the U.K., and it recently opened stores in New York and Hong Kong. In 2002 it had sales of more than £100m ($160 million). Its growth potential triggered McDonald's to buy a 33 percent share of the company.

What are the key reasons firsttier noncustomers want to jump ship and leave your industry? Look for the commonalities across their responses. Focus on these, and not on the differences between them. You will glean insight into how to desegment buyers and unleash an ocean of latent untapped demand.

Second-Tier Noncustomers

These are refusing noncustomers, people who either do not use or cannot afford to use the current market offerings because they find the offerings unacceptable or beyond their means. Their needs are either dealt with by other means or ignored. Harboring within refusing noncustomers, however, is an ocean of untapped demand waiting to be released.

Consider how JCDecaux, a vendor of French outdoor advertising space, pulled the mass of refusing noncustomers into its market. Before JCDecaux created a new concept in outdoor advertising called "street furniture" in 1964, the outdoor advertising industry included billboards and transport advertisement. Billboards typically were located on city outskirts and along roads where traffic quickly passed by; transport advertisement comprised panels on buses and taxies, which again people caught sight of only as they whizzed by.

Outdoor advertising was not a popular campaign medium for many companies because it was viewed only in a transitory way. Outdoor ads were exposed to people for a very short time while they were in transit, and the rate of repeat visits was low. Especially for lesser-known companies, such advertising media were ineffective because they could not carry the comprehensive messages needed to introduce new names and products. Hence, many such companies refused to use such low-value-added outdoor advertising because it was either unacceptable or a luxury they could not afford.

Having thought through the key commonalities that cut across refusing noncustomers of the industry, JCDecaux realized that the lack of stationary downtown locations was the key reason the industry remained unpopular and small. In searching for a solution, JCDecaux found that municipalities could offer stationary downtown locations, such as bus stops, where people tended to wait a few minutes and hence had time to read and be influenced by advertisements. JCDecaux reasoned that if it could secure these locations to use for outdoor advertising, it could convert second-tier noncustomers into customers.

This gave it the idea to provide street furniture, including maintenance and upkeep, free to municipalities. JCDecaux figured that as long as the revenue generated from selling ad space exceeded the costs of providing and maintaining the furniture at an attractive profit margin, the company would be on a trajectory of strong, profitable growth. Accordingly, street furniture was created that would integrate advertising panels.

In this way, JCDecaux created a breakthrough in value for second-tier noncustomers, the municipalities, and itself. The strategy eliminated cities' traditional costs associated with urban furniture. In return for free products and services, JCDecaux gained the exclusive right to display advertisements on the street furniture located in downtown areas. By making ads available in city centers, the company significantly increased the average exposure time, improving the recall capabilities of this advertising medium. The increase in exposure time also permitted richer contents and more complex messages. Moreover, as the maintainer of the urban furniture, JCDecaux could help advertisers roll out their campaigns in two to three days, as opposed to fifteen days of rollout time for traditional billboard campaigns.

In response to JCDecaux's exceptional value offering, the mass of refusing noncustomers flocked to the industry. As a medium of advertisement, street furniture became the highest-growth market in the overall display advertising industry. Global spending on street furniture between 1995 and 2000, for example, grew by 60 percent compared with a 20 percent total increase in overall display advertising.

By signing contracts of eight to twenty-five years with municipalities, JCDecaux gained long-term exclusive rights for displaying ads with street furniture. After an initial capital investment, the only expenditure for JCDecaux in the subsequent years was the maintenance and renewal of the furniture. The operating margin of street furniture was as high as 40 percent, compared with 14 per cent for billboards and 18 percent for transport advertisements. The exclusive contracts and high operating margins created a steady source of long-term revenue and profits. With this business model, JCDecaux was able to capture a leap in value for itself in return for a leap in value created for its buyers.

Today, JCDecaux is the number one street furniture-based ad space provider worldwide, with 283,000 panels in thirty-three countries. What's more, by looking to second-tier noncustomers and focusing on the key commonalities that turned them away from the industry, JCDecaux also increased the demand for outdoor advertising by existing customers of the industry. Until then, existing customers had focused on what billboard locations or bus lines they could secure, for what period, and for how much. They took for granted that those were the only options available and worked within them. Again, it took noncustomers to shed insight into the implicit assumptions of the industry and its existing customers that could be challenged and rewritten to create a leap in value for all.

What are the key reasons second-tier noncustomers refuse to use the products or services of your industry? Look for the commonalities across their responses. Focus on these, and not on their differences. You will glean insight into how to unleash an ocean of latent untapped demand.

ThirdTier Noncustomers

The third tier of noncustomers is the farthest away from an industry's existing customers. Typically, these unexplored noncustomers have not been targeted or thought of as potential customers by any player in the industry. That's because their needs and the business opportunities associated with them have somehow always been assumed to belong to other markets.

It would drive many companies crazy to know how many thirdtier noncustomers they are forfeiting. Just think of the long-held assumption that tooth whitening was a service provided exclusively by dentists and not by oral care consumer-product compa-flies. Consequently, oral care companies, until recently, never looked at the needs of these noncustomers. When they did, they found an ocean of latent demand waiting to be tapped; they also found that they had the capability to deliver safe, high-quality, low-cost tooth whitening solutions, and the market exploded.

This potential applies to most industries. Consider the U.S. defense aerospace industry. It has been argued that the inability to control aircraft costs is a key vulnerability in the long-term military strength of the United States.' Soaring costs combined with shrinking budgets, concluded a 1993 Pentagon report, left the military without a viable plan to replace its aging fleet of fighter aircraft.2 If the military couldn't find a way to build aircraft differently, military leaders worried, the United States would not have enough airplanes to properly defend its interests.

Traditionally, the Navy, Marines, and Air Force differed in their conceptions of the ideal fighter plane and hence each branch designed and built its own aircraft independently. The Navy argued for a durable aircraft that would survive the stress of landing on carrier decks. The Marines wanted an expeditionary aircraft capable of short takeoffs and landings. The Air Force wanted the fastest and most sophisticated aircraft.

Historically, these differences among the independent branches were taken for granted, and the defense aerospace industry was regarded as having three distinct and separate segments. The Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) program challenged this industry practice.3 It looked to all three segments as potentially unexplored noncustomers that could be aggregated into a new market of higher-performing, lower-cost fighter planes. Rather than accept the existing segmentation and develop products according to the differences in specifications and features demanded by each branch of the military, the JSF program questioned these differences. It searched for the key commonalities across the three branches that had previously disregarded one another.

This process revealed that the two highest-cost components of the three branches' aircraft were the same: avionics (software) and engines. The shared use and production of these components held the promise of enormous cost reductions. Moreover, even though each branch had a long list of highly customized requirements, most aircraft across branches performed the same missions.

The JSF team looked to understand how many of these highly customized features decisively influenced the branches' purchase decision. Interestingly, the Navy's answer did not hinge on a wide range of factors. Instead, it boiled down to only two: durability and maintainability. With aircraft stationed on aircraft carriers thousands of miles away from the nearest maintenance hangar, the Navy wants a fighter that is easy to maintain and yet durable as a Mack truck so that it can absorb the shock of carrier landings and constant exposure to salt air. Fearing that these two essential qualities would be compromised with the requirements of the Marines and the Air Force, the Navy bought its aircraft separately.

The Marines had many differences in requirements from those of the other branches, but again only two kept them from decisively avoiding joint aircraft purchases: the need for short takeoff vertical landing (STOVL) and robust countermeasures. To support troops in remote and hostile conditions the Marines need an aircraft that performs as a jet fighter and yet hovers like a helicopter. And given the low-altitude, expeditionary nature of their missions, the Marines want an aircraft equipped with various countermeasures-flares, electronic jamming devices to evade enemy groundto-air missiles because their planes are relatively easier targets given their short air-to-ground range.

Tasked with maintaining global air superiority, the Air Force demands the fastest aircraft and superior tactical agility the ability to outmaneuver all current and future enemy aircraft and one equipped with stealth technology: radar-absorbing materials and structures to make it less visible to radar and therefore more likely to evade enemy missiles and aircraft. The other two branches' aircraft lacked these factors, and hence the Air Force had not considered them.

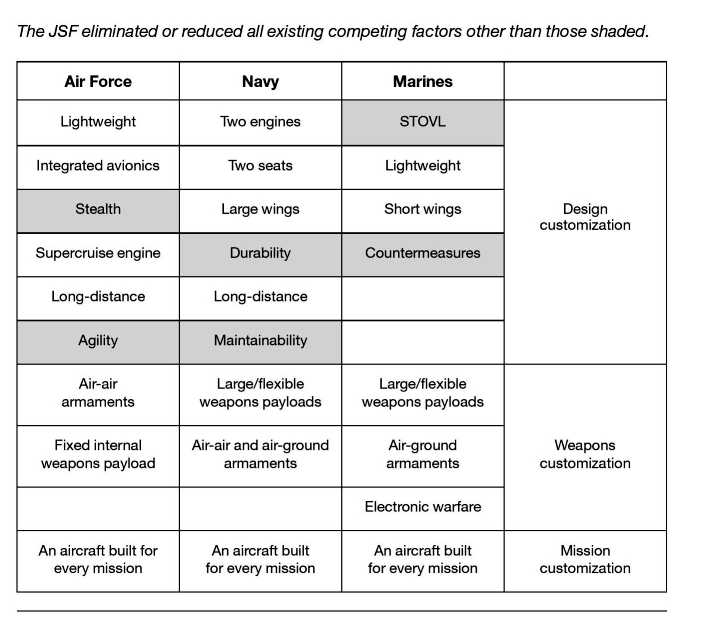

These findings on unexplored noncustomers made the JSF a feasible project. The aim was to build one aircraft for all three divisions by combining those key factors while reducing or eliminating everything else that is, all the factors that had been taken for granted by each branch but provided little value, or factors that had been overdesigned in the race to beat the competition. As outlined in figure 5-2, some twenty competing factors in the Marine, Navy, and Air Force segments were eliminated or reduced.

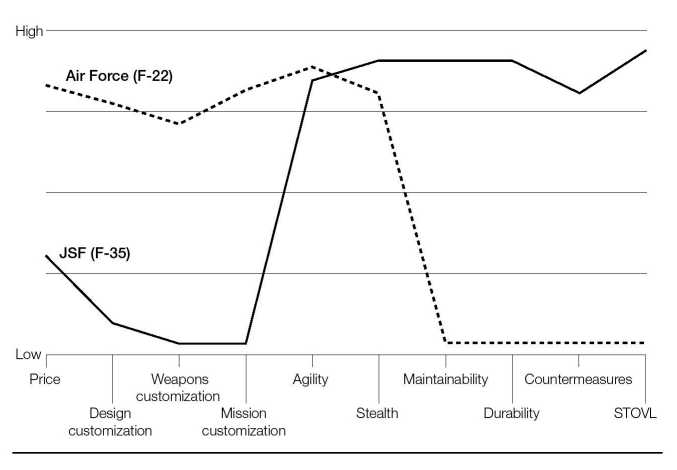

By combining the factors in this way and reducing or eliminating the rest, the JSF program is able to build one aircraft for all three branches. The result is a dramatic drop in costs and hence the price per aircraft, with a leap in value in performance for all three branches. Specifically, the JSF promised to reduce costs to $33 mil lion per aircraft from the current $190 million. At the same time, the performance of the JSF, now called the F-35, promised to be superior to that of any of the top-performing aircraft for the three branches: the Air Force's F-22, the Marine's AV-8B Harrier jet, and the Navy's F-18. Figure 5-3 illustrates how the JSF creates exceptional value by offering superior performance at lower costs.

FIGURE 5-2

The Key Competing Factors of the Defense Aerospace Industry, After JSF

As revealed in the figure, the strategy canvas shows that while the JSF roughly maintains the distinctive strengths of the Air Force's aircraft agility and stealth it also offers greater maintainability, durability, countermeasures, and STOVL, the key strengths required by the Navy and the Marines. These factors are powerful additions that the Air Force had assumed it could not have. By focusing on these key decisive factors and dropping or reducing all other factors in the three dominant domains of customization namely, design, weapons, and mission customization the JSF program was able to offer a superior fighter plane at a lower cost.

FIGURE 5-3

Joint Strike Fighter (F-35) Versus Air Force F-22

By reaching beyond the existing customers of each of the three military branches, the JSF aggregated demand previously divided among them. In fall 2001, Lockheed Martin was awarded the massive $200 billion JSF contract the largest military contract in history over Boeing. The first JSF F-35 is set to be delivered in 2010. To date, the Pentagon is confident that the program will be an unqualified success, not only because the strategic profile of the JSF F-35 achieves exceptional value but also, equally important, because it has won the support of all three defense branches.4

Go for the Biggest Catchment

There is no hard-and-fast rule to suggest which tier of noncustomers you should focus on and when. Because the scale of blue ocean opportunities that a specific tier of noncustomers can unlock varies across time and industries, you should focus on the tier that represents the biggest catchment at the time. But you should also explore whether there are overlapping commonalities across all three tiers of noncustomers. In that way, you can expand the scope of latent demand you can unleash. When that is the case, you should not focus on a specific tier but instead should look across tiers. The rule here is to go for the largest catchment.

The natural strategic orientation of many companies is toward retaining existing customers and seeking further segmentation opportunities. This is especially true in the face of competitive pressure. Although this might be a good way to gain a focused competitive advantage and increase share of the existing market space, it is not likely to produce a blue ocean that expands the market and creates new demand. The point here is not to argue that it's wrong to focus on existing customers or segmentation but rather to challenge these existing, taken-for-granted strategic orientations. What we suggest is that to maximize the scale of your blue ocean you should first reach beyond existing demand to noncustomers and desegmentation opportunities as you formulate future strategies.

If no such opportunities can be found, you can then move on to further exploit differences among existing customers. But in making such a strategic move, you should be aware that you might end up landing in a smaller space. You should also be aware that when your competitors succeed in attracting the mass of noncustomers with a value innovation move, many of your existing customers may be attracted away because they too may be willing to put their differences aside to gain the offered leap in value.

It is not enough to maximize the size of the blue ocean you are creating. You must profit from it to create a sustainable win-win outcome. The next chapter shows how to build a viable business model that produces and maintains profitable growth for your blue ocean offering.