Overcome Key Organizational Hurdles

INCE A COMPANY HAS DEVELOPED a blue ocean strategy with a profitable business model, it must execute it. The challenge of execution exists, of course, for any strategy. Companies, like individuals, often have a tough time translating thought into action whether in red or blue oceans. But compared with red ocean strategy, blue ocean strategy represents a significant departure from the status quo. It hinges on a shift from convergence to divergence in value curves at lower costs. That raises the execution bar.

INCE A COMPANY HAS DEVELOPED a blue ocean strategy with a profitable business model, it must execute it. The challenge of execution exists, of course, for any strategy. Companies, like individuals, often have a tough time translating thought into action whether in red or blue oceans. But compared with red ocean strategy, blue ocean strategy represents a significant departure from the status quo. It hinges on a shift from convergence to divergence in value curves at lower costs. That raises the execution bar.

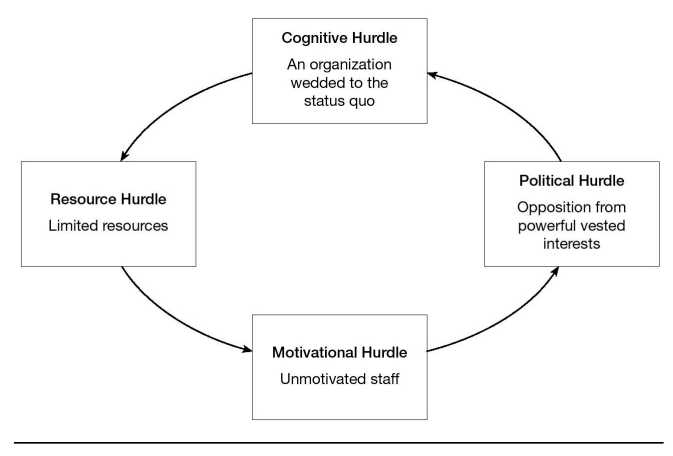

Managers have assured us that the challenge is steep. They face four hurdles. One is cognitive: waking employees up to the need for a strategic shift. Red oceans may not be the paths to future profitable growth, but they feel comfortable to people and may have even served an organization well until now, so why rock the boat?

The second hurdle is limited resources. The greater the shift in strategy, the greater it is assumed are the resources needed to execute it. But resources were being cut, and not raised, in many of the organizations we studied.

Third is motivation. How do you motivate key players to move fast and tenaciously to carry out a break from the status quo? That will take years, and managers don't have that kind of time.

The final hurdle is politics. As one manager put it, "In our organization you get shot down before you stand up."

Although all companies face different degrees of these hurdles, and many may face only some subset of the four, knowing how to triumph over them is key to attenuating organizational risk. This brings us to the fifth principle of blue ocean strategy: Overcome key organizational hurdles to make blue ocean strategy happen in action.

To achieve this effectively, however, companies must abandon perceived wisdom on effecting change. Conventional wisdom asserts that the greater the change, the greater the resources and time you will need to bring about results. Instead, you need to flip conventional wisdom on its head using what we call tipping point leadership. Tipping point leadership allows you to overcome these four hurdles fast and at low cost while winning employees' backing in executing a break from the status quo.

Tipping Point Leadership in Action

Consider the New York City Police Department (NYPD), which executed a blue ocean strategy in the 1990s in the public sector. When Bill Bratton was appointed police commissioner of New York City in February 1994, the odds were stacked against him to an extent few executives ever face. In the early 1990s, New York City was veering toward anarchy. Murders were at an all-time high. Muggings, Mafia hits, vigilantes, and armed robberies filled the daily headlines. New Yorkers were under siege. But Bratton's budget was frozen. Indeed, after three decades of mounting crime in New York City, many social scientists had concluded that it was impervious to police intervention. The citizens of New York City were crying out. A front-page headline in the New York Post had screamed: "Dave do something!" -a direct call to then mayor David Dinkins to get crime down fast.' With miserable pay, dangerous working conditions, long hours, and little hope of advancement in a tenure promotion system, morale among the NYPD's thirty-six thousand officers was at rock bottom not to mention the debilitating effects of budget cuts, dilapidated equipment, and corruption.

In business terms, the NYPD was a cash-strapped organization with thirty-six thousand employees wedded to the status quo, unmotivated, and underpaid; a disgruntled customer base New York City's citizens; and rapidly declining performance as measured by the increase in crime, fear, and disorder. Entrenched turf wars and politics topped off the cake. In short, leading the NYPD to execute a shift in strategy was a managerial nightmare far beyond the imaginations of most executives. The competition the criminals was strong and rising.

Yet in less than two years and without an increase in his budget, Bratton turned New York City into the safest large city in the United States. He broke out of the red ocean with a blue ocean policing strategy that revolutionized U.S. policing as it was then known. Between 1994 and 1996, the organization won as "profits" jumped: Felony crime fell 39 percent, murders 50 percent, and theft 35 percent. "Customers" won: Gallup polls reported that public confidence in the NYPD leaped from 37 percent to 73 percent. And employees won: Internal surveys showed job satisfaction in the NYPD reaching an all-time high. As one patrolman put it, "We would have marched to hell and back for that guy." Perhaps most impressively, the changes have outlasted its leader, implying a fundamental shift in the organizational culture and strategy of the NYPD. Even after Bratton's departure in 1996, crime rates have continued to fall.

Few corporate leaders face organizational hurdles as steep as Bratton did in executing a break from the status quo. And still fewer are able to orchestrate the type of performance leap that Bratton achieved under any organizational conditions, let alone those as stringent as he encountered. Even Jack Welch needed some ten years and tens of millions of dollars of restructuring and training to turn GE into a powerhouse.

Moreover, defying conventional wisdom, Bratton achieved these breakthrough results in record time with scarce resources while lifting employee morale, creating a win-win for all involved. Nor was this Bratton's first strategic reversal. It was his fifth, with each of the others also achieved despite his facing all four hurdles that managers consistently claim limit their ability to execute blue ocean strategy: the cognitive hurdle that blinds employees from seeing that radical change is necessary; the resource hurdle that is endemic in firms; the motivational hurdle that discourages and demoralizes staff; and the political hurdle of internal and external resistance to change (see figure 7-1).

FIGURE 7-1

The Four Organizational Hurdles to Strategy Execution

The Pivotal Lever: Disproportionate Influence Factors

Tipping point leadership traces its roots to the field of epidemiology and the theory of tipping points.' It hinges on the insight that in any organization, fundamental changes can happen quickly when the beliefs and energies of a critical mass of people create an epidemic movement toward an idea. Key to unlocking an epidemic movement is concentration, not diffusion.

Tipping point leadership builds on the rarely exploited corporate reality that in every organization, there are people, acts, and activities that exercise a disproportionate influence on performance. Hence, contrary to conventional wisdom, mounting a massive challenge is not about putting forth an equally massive response where performance gains are achieved by proportional investments in time and resources. Rather, it is about conserving resources and cutting time by focusing on identifying and then leveraging the factors of disproportionate influence in an organization.

The key questions answered by tipping point leaders are as follows: What factors or acts exercise a disproportionately positive influence on breaking the status quo? On getting the maximum bang out of each buck of resources? On motivating key players to aggressively move forward with change? And on knocking down political roadblocks that often trip up even the best strategies? By singlemindedly focusing on points of disproportionate influence, tipping point leaders can topple the four hurdles that limit execution of blue ocean strategy. They can do this fast and at low cost.

Let us consider how you can leverage disproportionate influence factors to tip all four hurdles to move from thought to action in the execution of blue ocean strategy.

Break Through the Cognitive Hurdle

In many turnarounds and corporate transformations, the hardest battle is simply to make people aware of the need for a strategic shift and to agree on its causes. Most CEOs will try to make the case for change simply by pointing to the numbers and insisting that the company set and achieve better results: "There are only two performance alternatives: to make the performance targets or to beat them."

But as we all know, figures can be manipulated. Insisting on stretch goals encourages abuse in the budgetary process. This, in turn, creates hostility and suspicion between the various parts of an organization. Even when the numbers are not manipulated, they can mislead. Salespeople on commission, for example, are seldom sensitive to the costs of the sales they produce.

What's more, messages communicated through numbers seldom stick with people. The case for change feels abstract and removed from the sphere of the line managers, who are the very people the CEO needs to win over. Those whose units are doing well feel that the criticism is not directed at them; the problem is top management's. Meanwhile, managers of poorly performing units feel that they are being put on notice, and people who are worried about personal job security are more likely to scan the job market than to try to solve the company's problems.

Tipping point leadership does not rely on numbers to break through the organization's cognitive hurdle. To tip the cognitive hurdle fast, tipping point leaders such as Bratton zoom in on the act of disproportionate influence: making people see and experience harsh reality firsthand. Research in neuroscience and cognitive science shows that people remember and respond most effectively to what they see and experience: "Seeing is believing." In the realm of experience, positive stimuli reinforce behavior, whereas negative stimuli change attitudes and behavior. Simply put, if a child puts a finger in icing and tastes it, the better it tastes the more the child will taste it repetitively. No parental advice is needed to encourage that behavior. Conversely, after a child puts a finger on a burning stove, he or she will never do it again. After a negative experience, children will change their behavior of their own accord; again, no parental pestering is required.3 On the other hand, experiences that don't involve touching, seeing, or feeling actual results, such as being presented with an abstract sheet of numbers, are shown to be non-impactful and easily forgotten.4

Tipping point leadership builds on this insight to inspire a fast change in mindset that is internally driven of people's own accord. Instead of relying on numbers to tip the cognitive hurdle, they make people experience the need for change in two ways.

Ride the "Electric Sewer"

To break the status quo, employees must come face-to-face with the worst operational problems. Don't let top brass, middle brass, or any brass hypothesize about reality. Numbers are disputable and uninspiring, but coming face-to-face with poor performance is shocking and inescapable, but actionable. This direct experience exercises a disproportionate influence on tipping people's cognitive hurdle fast.

Consider this example. In the 1990s the New York subway system reeked of fear, so much so that it earned the epithet "electric sewer." Revenues were tumbling fast as citizens boycotted the system. But members of the New York City Transit Police department were in denial. Why? Only 3 percent of the city's major crimes happened on the subway. So no matter how much the public cried out, their cries fell on deaf ears. There was no perceived need to rethink police strategies.

Then Bratton was appointed chief, and in a matter of weeks he orchestrated a complete break from the status quo in the mindset of the city's police. How? Not by force, nor by arguing for numbers, but by making top brass and middle brass starting with himself ride the electric sewer day and night. Until Bratton came along, that had not been done.

Although the statistics may have told the police that the subway was safe, what they now saw was what every New Yorker faced every day: a subway system on the verge of anarchy. Gangs of youths patrolled the cars, people jumped turnstiles, and the riders faced graffiti, aggressive begging, and winos sprawled over benches. The police could no longer evade the ugly truth. No one could argue that current police strategies didn't require a substantial departure from the status quo and fast.

Showing the worst reality to your superiors can also shift their mindset fast. A similar approach works to help sensitize superiors to a leader's needs fast. Yet few leaders exploit the power of this rapid wake-up call. Rather, they do the opposite. They try to garner support based on a numbers case that lacks urgency and emotional impetus. Or they try to put forth the most exemplary case of their operational excellence to garner support. Although these alternatives may work, neither leads to tipping superiors' cognitive hurdle as fast and stunningly as showing the worst.

When Bratton, for example, was running the police division of the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA), the MBTA board decided to purchase small squad cars that would be cheaper to buy and to run. That went against Bratton's new policing strategy. Instead of fighting the decision, however, or arguing for a larger budget something that would have taken months to reevaluate and probably would have been rejected in the endBratton invited the MBTA's general manager for a tour of his unit to see the district.

To let the general manager see the horror he was trying to rectify, Bratton picked him up in a small car just like the ones that were being ordered. He jammed the seats up front to let the manager feel how little legroom a six-foot cop would get, and then Bratton drove over every pothole he could. Bratton also put on his belt, cuffs, and gun for the trip so that the manager would see how little space there was for the tools of the police officer's trade. After two hours, the general manager wanted out. He told Bratton he didn't know how Bratton could stand being in such a cramped car for so long on his own, never mind having a criminal in the back seat. Bratton got the larger cars his new strategy demanded.

Meet with Disgruntled Customers

To tip the cognitive hurdle, not only must you get your managers out of the office to see operational horror, but also you must get them to listen to their most disgruntled customers firsthand. Don't rely on market surveys. To what extent does your top team actively observe the market firsthand and meet with your most disgruntled customers to hear their concerns? Do you ever wonder why sales don't match your confidence in your product? Simply put, there is no substitute for meeting and listening to dissatisfied customers directly.

In the late 1970s, Boston's Police District 4, which housed the Symphony Hall, Christian Science Mother Church, and other cultural institutions, was experiencing a serious surge in crime. The public was increasingly intimidated; residents were selling their homes and leaving, thereby pushing the community into a downward spiral. But even though the citizens were leaving the area in droves, the police force under Bratton's direction felt they were doing a fine job. The performance indicators they historically used to benchmark themselves against other police departments were tip-top: 911 response times were down, and felony crime arrests were up. To solve the paradox Bratton arranged a series of town hall meetings between his officers and the neighborhood residents.

It didn't take long to find the gap in perceptions. Although the police officers took great pride in short response times and their record in solving major crimes, these efforts went unnoticed and unappreciated by citizens; few felt endangered by large-scale crimes. What they felt victimized by and harassed by were the constant minor irritants: winos, panhandlers, prostitutes, and graffiti.

The town meetings led to a complete overhaul of police priorities to focus on the blue ocean strategy of "broken windows."5 Crime went down, and the neighborhood felt safe again.

When you want to wake up your organization to the need for a strategic shift and a break from the status quo, do you make your case with numbers? Or do you get your managers, employees, and superiors (and yourself) face-to-face with your worst operational problems? Do you get your managers to meet the market and listen to disenchanted customers holler? Or do you outsource your eyes and send out market research questionnaires?

Jump the Resource Hurdle

After people in an organization accept the need for a strategic shift and more or less agree on the contours of the new strategy, most leaders are faced with the stark reality of limited resources. Do they have the money to spend on the necessary changes? At this point, most reformist CEOs do one of two things. Either they trim their ambitions and demoralize their work force all over again, or they fight for more resources from their bankers and shareholders, a process that can take time and divert attention from the underlying problems. That's not to say that this approach is not necessary or worthwhile, but acquiring more resources is often a long, politically charged process.

How do you get an organization to execute a strategic shift with fewer resources? Instead of focusing on getting more resources, tipping point leaders concentrate on multiplying the value of the resources they have. When it comes to scarce resources, there are three factors of disproportionate influence that executives can leverage to dramatically free resources, on the one hand, and multiply the value of resources, on the other. These are hot spots, cold spots, and horse trading.

Hot spots are activities that have low resource input but high potential performance gains. In contrast, cold spots are activities that have high resource input but low performance impact. In every organization, hot spots and cold spots typically abound. Horse trading involves trading your unit's excess resources in one area for another unit's excess resources to fill remaining resource gaps. By learning to use their current resources right, companies often find they can tip the resource hurdle outright.

What actions consume your greatest resources but have scant performance impact? Conversely, what activities have the greatest performance impact but are resource starved? When the questions are framed in this way, organizations rapidly gain insight into freeing up low-return resources and redirecting them to high-impact areas. In this way, both lower costs and higher value are simultaneously pursued and achieved.

Redistribute Resources to your Hot Spots

At the New York Transit Police, Bratton's predecessors argued that to make the city's subways safe they had to have an officer ride every subway line and patrol every entrance and exit. To increase profits (lower crime) would mean increasing costs (police officers) in multiples that were not possible given the budget. The underlying logic was that increments in performance could be achieved only with proportional increments in resources the same inherent logic guiding most companies' view of performance gains.

Bratton, however, achieved the sharpest drop in subway crime, fear, and disorder in Transit's history, not with more police officers but with police officers targeted at hot spots. His analysis revealed that although the subway system was a maze of lines and entrances and exits, the vast majority of crimes occurred at only a few stations and on a few lines. He also found that these hot spots were starved for police attention even though they exercised a disproportionate impact on crime performance, whereas lines and stations that almost never reported criminal activity were staffed equally. The solution was a complete refocusing of cops at subway hot spots to overwhelm the criminal element. And crime came tumbling down while the size of the police force remained constant.

Similarly, before Bratton's arrival at the NYPD the narcotics unit worked nine-to-five weekday-only shifts and made up less than 5 percent of the department's human resources. To search out resource hot spots, in one of his initial meetings with the NYPD's chiefs Bratton's deputy commissioner of crime strategy, Jack Maple, asked people around the table for their estimates of the percentage of crimes attributable to narcotics usage. Most said 50 percent, others 70 percent; the lowest estimate was 30 percent. On that basis, as Maple pointed out, it was hard to argue that a narcotics unit consisting of less than 5 percent of the NYPD force was not grossly understaffed. What's more, it turned out that the narcotics squad largely worked Monday to Friday, even though most drugs were sold over the weekend, when drug-related crimes persistently occurred. Why? That was the way it had always been; it was the unquestioned modus operandi.

When these facts were presented and the hot spot identified, Bratton's case for a major reallocation of staff and resources within the NYPD was quickly accepted. Accordingly, Bratton reallocated staff and resources on the hot spot, and drug crime plummeted.

Where did he get the resources to do this? He simultaneously assessed his organization's cold spots.

Redirect Resources from your Cold Spots

Leaders need to free up resources by searching out cold spots. Again in the subway, Bratton found that one of the biggest cold spots was processing criminals in court. On average, it would take an officer sixteen hours to take someone downtown to process even the pettiest of crimes. This was time officers were not patrolling the subway and adding value.

Bratton changed all that. Instead of bringing criminals to the court, he brought processing centers to the criminals by using "bust buses" roving old buses retrofitted into miniature police stations that were parked outside subway stations. Now instead of dragging a suspect down to the courthouse across town, a police officer needed only escort the suspect up to street level to the bus. This cut processing time from sixteen hours to just one, freeing more officers to patrol the subway and catch criminals.

Engage in Horse Trading

In addition to internally refocusing the resources a unit already controls, tipping point leaders skillfully trade resources they don't need for those of others that they do need. Consider again the case of Bratton. The chiefs of public sector organizations know that the size of their budgets and the number of people they control are often hotly debated because public sector resources are notoriously limited. This makes chiefs of public sector organizations unwilling to advertise excess resources, let alone release them for use by other parts of the larger organization, because that would risk a loss of control over those resources. One result is that over time, some organizations become well endowed with resources they don't need even while they are short of ones they do need.

On taking over as chief of the New York Transit Police in 1990, Bratton's general counsel and policy adviser, Dean Esserman (now police chief of Providence, Rhode Island), played a key horse trading role. Esserman discovered that the Transit unit, which was starved for office space, had been running a fleet of unmarked cars in excess of its needs. The New York Division of Parole, on the other hand, was short of cars but had excess office space. Esserman and Bratton offered the obvious trade, which was gratefully accepted by the parole officials. For their part, Transit unit officers were delighted to get the first floor of a prime downtown building. The deal stoked Bratton's credibility within the organization, something that later made it easier for him to introduce more fundamental changes. At the same time, it marked him to his political bosses as a man who could solve problems.

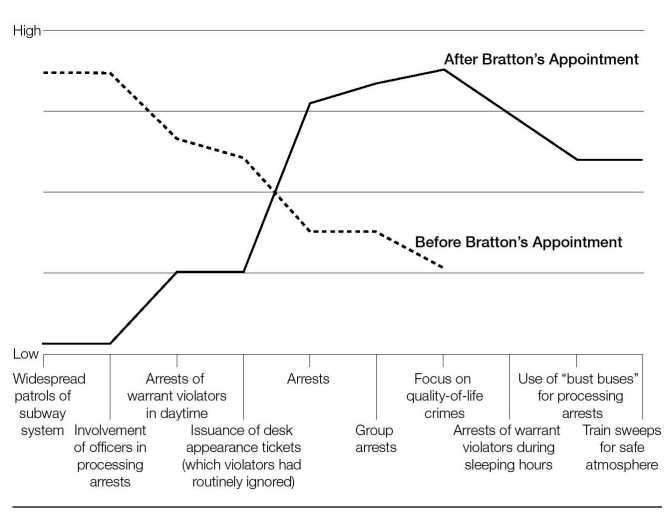

Figure 7-2 illustrates how radically Bratton refocused the Transit Police department's resources to break out of the red ocean and execute its blue ocean strategy. The vertical axis here shows the relative level of resource allocation, and the horizontal axis shows the various elements of strategy in which the investments were made. By deemphasizing or virtually eliminating some traditional features of transit police work while increasing emphasis on the others or creating new ones, Bratton achieved a dramatic shift in resource allocation.

Whereas the actions of eliminating and reducing cut the costs for the organization, raising certain elements or creating new ones required added investments. As you can see on the strategy canvas, however, the overall investment of resources remained more or less constant. At the same time, the value to citizens went way up. Eliminating the practice of widespread coverage of the subway system and replacing it with a targeted strategy on hot spots enabled the transit police to combat subway crimes more efficiently and effectively. Reducing the involvement of officers in processing arrests or cold spots and creating bust buses significantly raised the value of the police force by allowing officers to concentrate their time and attention on policing the subway. Raising the level of investment in combating quality-of-life crimes rather than big crimes refocused the police resources on crimes that presented constant dangers to citizens' daily lives. Through these moves, the New York Transit Police significantly enhanced the performance of its officers, who were now freed from administrative hassles and assigned clear du ties as to what kinds of crimes they should focus on and where to combat them.

FIGURE 7-2

The Strategy Canvas of Transit: How Bratton Refocused Resources

Are you allocating resources based on old assumptions, or do you seek out and concentrate resources on hot spots? Where are your hot spots? What activities have the greatest performance impact but are resource starved? Where are your cold spots? What activities are resource oversupplied but have scant performance impact? Do you have a horse trader, and what can you trade?

Jump the Motivational Hurdle

To reach your organization's tipping point and execute blue ocean strategy, you must alert employees to the need for a strategic shift and identify how it can be achieved with limited resources. For a new strategy to become a movement, people must not only recognize what needs to be done, but they must also act on that insight in a sustained and meaningful way.

How can you motivate the mass of employees fast and at low cost? When most business leaders want to break from the status quo and transform their organizations, they issue grand strategic visions and turn to massive top-down mobilization initiatives. They act on the assumption that to create massive reactions, proportionate massive actions are required. But this is often a cumbersome, expensive, and time-consuming process, given the wide variety of motivational needs in most large companies. And overarching strategic visions often inspire lip service instead of the intended action. It would be easier to turn an aircraft carrier around in a bathtub.

Or is there another way? Instead of diffusing change efforts widely, tipping point leaders follow a reverse course and seek massive concentration. They focus on three factors of disproportionate influence in motivating employees, what we call kingpins, fishbowl management, and atomization.

Zoom in on Kingpins

For strategic change to have real impact, employees at every level must move en masse. To trigger an epidemic movement of positive energy, however, you should not spread your efforts thin. Rather, you should concentrate your efforts on kingpins, the key influencers in the organization. These are people inside the organization who are natural leaders, who are well respected and persuasive, or who have an ability to unlock or block access to key resources. As with kingpins in bowling, when you hit them straight on, all the other pins come toppling down. This frees an organization from tackling everyone, and yet in the end everyone is touched and changed. And because in most organizations there are a relatively small number of key influencers, who tend to share common problems and concerns, it is relatively easy for the CEO to identify and motivate them.

At the NYPD, for example, Bratton zoomed in on the seventy-six precinct heads as his key influencers and kingpins. Why? Each precinct head directly controlled two hundred to four hundred police officers. Hence, galvanizing these seventy-six heads would have the natural ripple effect of touching and motivating the thirty-sixthousand-deep police force to embrace the new policing strategy.

Place Kingpins in a Fishbowl

At the heart of motivating the kingpins in a sustained and meaningful way is to shine a spotlight on their actions in a repeated and highly visible way. This is what we refer to as fishbowl management, where kingpins' actions and inaction are made as transparent to others as are fish in a bowl of water. By placing kingpins in a fishbowl in this way you greatly raise the stakes of inaction. Light is shined on who is lagging behind, and a fair stage is set for rapid change agents to shine. For fishbowl management to work it must be based on transparency, inclusion, and fair process.

At the NYPD, Bratton's fishbowl was a biweekly crime strategy review meeting known as Compstat that brought together the city's top brass to review the performance of all the seventy-six precinct commanders in executing its new strategy. Attendance was mandatory for all precinct commanders; three-star chiefs, deputy commissioners, and borough chiefs were also required to attend. Bratton himself was there as often as possible. As each precinct commander was questioned on decreases and increases in crime performance in front of peers and superiors based on the organization's new strategic directives, enormous computer-generated overhead maps and charts were shown, visually illustrating in inescapable terms the commander's performance in executing the new strategy. The commander was responsible for explaining the maps, describing how his or her officers were addressing the issues, and outlining why performance was going up or down. These inclusive meetings instantly made results and responsibilities clear and transparent for everyone.

As a result, an intense performance culture was created in weeks forget about months, let alone years because no kingpin wanted to be shamed in front of others, and they all wanted to shine in front of their peers and superiors. In the fishbowl, incompetent precinct commanders could no longer cover up their failings by blaming their precinct's results on the shortcomings of neighboring precincts, because their neighbors were in the room and could respond. Indeed, a picture of the precinct commander to be grilled at the crime strategy meetings was printed on the front page of the handout, emphasizing that the commander was responsible and accountable for that precinct's results.

By the same token, the fishbowl gave an opportunity for high achievers to gain recognition for work in their own precincts and in helping others. The meetings also provided an opportunity for policy leaders to compare notes on their experiences; before Bratton's arrival, precinct commanders seldom got together as a group. Over time, this style of fishbowl management filtered down the ranks, as the precinct commanders tried out their own versions of Bratton's meetings. With the spotlight shining brightly on their performance in strategy execution, the precinct commanders were highly motivated to get all the officers under their control marching to the new strategy.

For this to work, however, organizations must simultaneously make fair process the modus operandi. By fair process we mean engaging all the affected people in the process, explaining to them the basis of decisions and the reasons people will be promoted or sidestepped in the future, and setting clear expectations of what that means to employees' performance. At the NYPD's crime strategy review meetings, no one could argue that the playing field wasn't fair. The fishbowl was applied to all kingpins. There was clear transparency in the assessment of every commander's performance and how it would tie into advancement or demotion, and clear expectations were set in every meeting of what was expected in performance from everyone.

In this way, fair process signals to people that there is a level playing field and that leaders value employees' intellectual and emotional worth despite all the change that may be required. This greatly mitigates feelings of suspicion and doubt that are almost necessarily present in employees' minds when a company is trying to make a major strategic shift. The cushion of support provided by fair process, combined with the fishbowl emphasis on sheer performance, pushes people and supports them on the journey, demonstrating managers' intellectual and emotional respect for employees. (For a fuller discussion on fair process and its motivational implications, see chapter 8.)

Atomize to Get the Organization to Change Itself

The last disproportionate influence factor is atomization. Atomization relates to the framing of the strategic challenge one of the most subtle and sensitive tasks of the tipping point leader. Unless people believe that the strategic challenge is attainable, the change is not likely to succeed. On the face of it, Bratton's goal in New York City was so ambitious as to be scarcely believable. Who could believe that anything an individual could do would turn such a huge city from being the most dangerous place in the country into the safest? And who would want to invest time and energy in chasing an impossible dream?

To make the challenge attainable, Bratton broke it into bite-size atoms that officers at different levels could relate to. As he put it, the challenge facing the NYPD was to make the streets of New York City safe "block by block, precinct by precinct, and borough by borough." Thus framed, the challenge was both all-encompassing and doable. For officers on the street, the challenge was to make their beat or block safe-no more. For the precinct commanders, the challenge was to make their precinct safe no more. Borough heads also had a concrete goal within their capabilities: making their boroughs safe-no more. No one could say that what was being asked of them was too tough. Nor could they claim that achieving it was largely out of their hands "It's beyond me." In this way, responsibility for executing Bratton's blue ocean strategy shifted from him to each of the NYPD's thirty-six thousand officers.

Do you indiscriminately try to motivate the masses? Or do you focus on key influencers, your kingpins? Do you put the spotlight on and manage kingpins in a fishbowl based on fair process? Or do you just demand high performance and cross your fingers until the next quarter numbers come out? Do you issue grand strategic visions? Or do you atomize the issue to make it actionable to all levels?

Knock Over the Political Hurdle

Youth and skill will win out every time over age and treachery. True or false? False. Even the best and brightest are regularly eaten alive by politics, intrigue, and plotting. Organizational politics is an inescapable reality of corporate and public life. Even if an organization has reached the tipping point of execution, there exist powerful vested interests that will resist the impending changes. (Also see our discussion on adoption hurdles in chapter 6.) The more likely change becomes, the more fiercely and vocally these negative influencers both internal and external will fight to protect their positions, and their resistance can seriously damage and even derail the strategy execution process.

To overcome these political forces, tipping point leaders focus on three disproportionate influence factors: leveraging angels, silencing devils, and getting a consigliere on their top management team. Angels are those who have the most to gain from the strategic shift. Devils are those who have the most to lose from it. And a consigliere is a politically adept but highly respected insider who knows in advance all the land mines, including who will fight you and who will support you.

Secure a Consigliere on your Top Management Team

Most leaders concentrate on building a top management team having strong functional skills such as marketing, operations, and finance-and that is important. Tipping point leaders, however, also engage one role few other executives think to include: a consigliere. To that end, Bratton, for example, always ensured that he had a respected senior insider on his top team who knew the land mines he would face in implementing the new policing strategy. At NYPD, Bratton appointed John Timoney (now the police commissioner of Miami) as his number two. Timoney was a cop's cop, respected and feared for his dedication to the NYPD and for the more than sixty decorations and combat crosses he had received. Twenty years in the ranks had taught him not only who all the key players were but also how they played the political game. One of the first tasks Timoney did was to report to Bratton on the likely attitudes of the top staff to the NYPD's new policing strategy, identifying those who would fight or silently sabotage the new initiative. This led to a dramatic changing of the guard.

Leverage your Angels and Silence Your Devils

To knock down the political hurdles, you should also ask yourself two sets of questions:

• Who are my devils? Who will fight me? Who will lose the most by the future blue ocean strategy?

• Who are my angels? Who will naturally align with me? Who will gain the most by the strategic shift?

Don't fight alone. Get the higher and wider voice to fight with you. Identify your detractors and supporters forget the middle and strive to create a win-win outcome for both. But move quickly. Isolate your detractors by building a broader coalition with your angels before a battle begins. In this way, you will discourage the war before it has a chance to start or gain steam.

One of the most serious threats to Bratton's new policing strategy came from New York City's courts. Believing that Bratton's new policing strategy of focusing on quality-of-life crimes would overwhelm the system with small crime cases such as prostitution and public drunkenness, the courts opposed the strategic shift. To overcome this opposition, Bratton clearly illustrated to his supporters, including the mayor, district attorneys, and jail managers, that the court system could indeed handle the added quality-of-life crimes and that focusing on them would, in the long term, actually reduce their caseload. The mayor decided to intervene.

Then Bratton's coalition, led by the mayor, went on the offensive in the press with a clear and simple message: If the courts did not pull their weight, the city's crime rate would not go down. Bratton's alliance with the mayor's office and the city's leading newspaper successfully isolated the courts. They could hardly be seen to publicly oppose an initiative that would not only make New York a more attractive place to live but would also ultimately reduce the number of cases brought before them. With the mayor speaking aggressively in the press of the need to pursue quality-of-life crimes and the city's most respected and liberal newspaper giving credence to the new police strategy, the costs of fighting Bratton's strategy were daunting. Bratton had won the battle: The courts would comply. He also won the war: Crime rates did indeed come down.

Key to winning over your detractors or devils is knowing all their likely angles of attack and building up counterarguments backed by irrefutable facts and reason. For example, when the NYPD's precinct commanders were first requested to compile detailed crime data and maps, they balked at the idea, arguing that it would take too much time. Anticipating this reaction, Bratton had already done a test run of the operation to see how long it would take: no more than eighteen minutes a day, which worked out, as he told the commanders, to less than 1 percent of their average workload. Armed with irrefutable information, he was able to tip the political hurdle and win the battle before it even began.

Do you have a consigliere-a highly respected insider in your top management team, or only a CFO and other functional head heads? Do you know who will fight you and who will align with the new strategy? Have you built coalitions with natural allies to encircle dissidents? Do you have your consigliere remove the biggest land mines so that you don't have to focus on changing those who cannot and will not change?

Challenging Conventional Wisdom

As shown in figure 7-3, the conventional theory of organizational change rests on transforming the mass. So change efforts are focused on moving the mass, requiring steep resources and long time frames luxuries few executives can afford. Tipping point leadership, by contrast, takes a reverse course. To change the mass it focuses on transforming the extremes: the people, acts, and activities that exercise a disproportionate influence on performance. By transforming the extremes, tipping point leaders are able to change the core fast and at low cost to execute their new strategy.

FIGURE 7-3

Conventional Wisdom Versus Tipping Point Leadership

It is never easy to execute a strategic shift, and doing it fast with limited resources is even more difficult. Yet our research suggests that it can be achieved by leveraging tipping point leadership. By consciously addressing the hurdles to strategy execution and focusing on factors of disproportionate influence, you too can knock them over to actualize a strategic shift. Don't follow conventional wisdom. Not every challenge requires a proportionate action. Focus on acts of disproportionate influence. This is a critical leadership component for making blue ocean strategy happen. It aligns employees' actions with the new strategy.

The next chapter drills down one level further. It addresses the challenge of aligning people's minds and hearts with the new strategy by building a culture of trust, commitment, and voluntary cooperation in its execution, as well as support for the leader. Addressing this challenge spells the difference between forced execution and voluntary execution driven by people's free will.