The Market Dynamics of Value Innovation

SHE MARKET DYNAMICS of value innovation stand in stark contrast with the conventional practice of technology innovation. The latter typically sets high prices, limits access, and initially engages in price skimming to earn a premium on the innovation, only later focusing on lowering prices and costs to retain market share and discourage imitators.

SHE MARKET DYNAMICS of value innovation stand in stark contrast with the conventional practice of technology innovation. The latter typically sets high prices, limits access, and initially engages in price skimming to earn a premium on the innovation, only later focusing on lowering prices and costs to retain market share and discourage imitators.

However, in a world of nonrival and nonexcludable goods, such as knowledge and ideas, that are imbued with the potential of economies of scale, learning, and increasing returns, the importance of volume, price, and cost grows in an unprecedented way.' Under these conditions, companies would do well to capture the mass of target buyers from the outset and expand the size of the market by offering radically superior value at price points accessible to them.

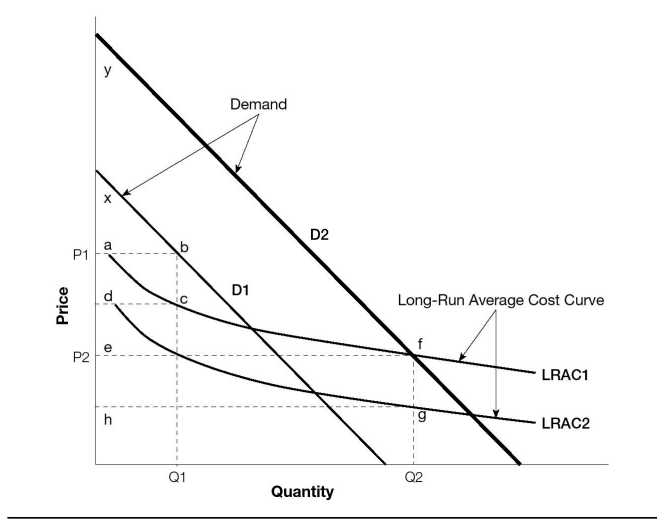

As shown in Figure C-1, value innovation radically increases the appeal of a good, shifting the demand curve from D1 to D2. The price is set strategically and, as with the Swatch example, is shifted from P1 to P2 to capture the mass of buyers in the expanded market. This increases the quantity sold from Q1 to Q2 and builds strong brand recognition, for unprecedented value.

FIGURE C-1

The Market Dynamics of Value Innovation

The company, however, engages in target costing to simultaneously reduce the longrun average cost curve from LRAC1 to LRAC2 to expand its ability to profit and to discourage free riding and imitation. Hence, buyers receive a leap in value, shifting the consumer surplus from axb to eyf. And the company earns a leap in profit and growth, shifting the profit zone from abcd to efgh.

The rapid brand recognition built by the company as a result of the unprecedented value offered in the marketplace, combined with the simultaneous drive to lower costs, makes the competition nearly irrelevant and makes it hard to catch up, as economies of scale, learning, and increasing returns kick in. What follows is the emergence of win-win market dynamics, where companies earn dominant positions while buyers also come out big winners.

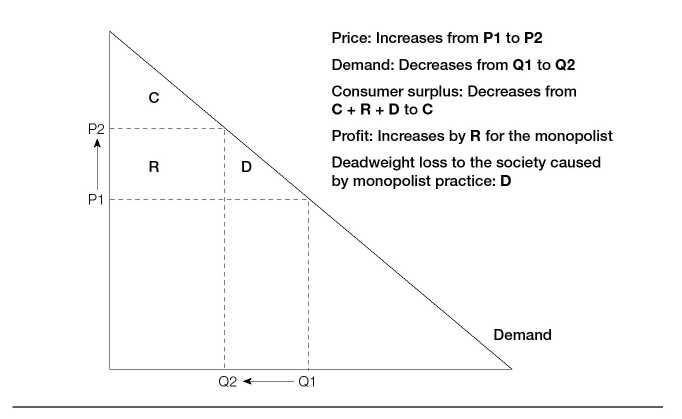

Traditionally, firms with monopolistic positions have been associated with two social welfare loss activities. First, to maximize their profits, companies set prices high. This prohibits those customers who, although desiring the product, cannot afford to buy it. Second, lacking viable competition, firms with monopolistic positions often do not focus on efficiency and cost reduction and hence consume more scarce resources. As Figure C-2 shows, under conventional monopolistic practice, the price level is raised from P1 under perfect competition to P2 under monopoly. Consequently, demand drops from Q1 to Q2. At this level of demand, the monopolist increases its profits by the area R, as opposed to the situation of perfect competition. Because of the artificially high price imposed on consumers, the consumer surplus decreases from area C+R+D to area C. Meanwhile, the monopolistic practice, by consuming more of the society's resources, also incurs a deadweight loss of area D for the society at large. Monopolistic profits, therefore, are achieved at the expense of consumers and society at large.

FIGURE C-2

From Perfect Competition to Monopolist Practice

Blue ocean strategy, on the other hand, works against this sort of price skimming, which is common to traditional monopolists. The focus of blue ocean strategy is not on restricting output at a high price but rather on creating new aggregate demand through a leap in buyer value at an accessible price. This creates a strong incentive not only to reduce costs to the lowest possible level at the start but also to keep it that way over time to discourage potential freeriding imitators. In this way, buyers win and the society benefits from improved efficiency. This creates a win-win scenario. A breakthrough in value is achieved for buyers, for the company, and for society at large.