Part 1 How You Think 中

Main Idea

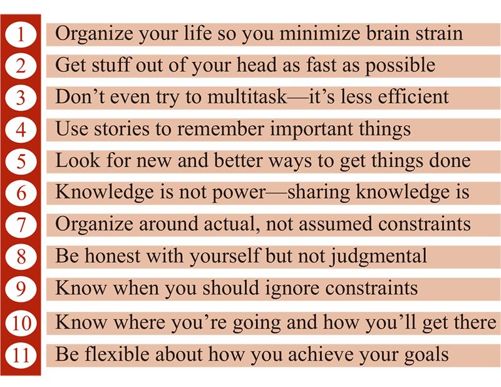

It makes good sense to align your personal organization system with the way you think. If you don't do this, you inadvertently end up sabotaging your best efforts to move ahead.The eleven principles that help you do this are:

Supporting Ideas

Your life is chock full of items that are all clamoring for your attention. Regardless of whether you realize it or not, your attention is constantly wandering from one thing to another to still something else. Information is washing over you all the time, so don't even try to take notice of everything you come across. Instead, you should try to organize your life in ways that minimize mental strain.

Organize your life so you minimize brain strain

Key Thoughts

"Believe it or not, the way our brains work is one of the biggest challenges we face in getting organized. Honestly, I'm not here to give you rules. Rules are meant to restrict you. My principles are simply meant to suggest new ideas, options, and tools, so you can design systems for organizing that work for you."

-Douglas Merrill

The biggest cause of brain strain arises when we try to decide what to memorize and what to forget. The human brain is very good at noticing things but very poor at memorizing. Paying attention to what's happening around you was developed as a survival mechanism first and foremost, and we are on alert all the time, whether we realize it or not. When you notice something, it goes into your short-term memory. If you then do nothing further, that memory will get overwritten by something new. Your short-term memory can hold between five and nine things at any one time. One of the main keys in any system for getting better organized is to figure out ways to effectively get things out of your short-term memory and safely stored somewhere secure you can access in the future. If you can work towards putting in place systems that will make this happen consistently well, then you will automatically feel less stressed. You will suffer less brain strain and accordingly feel more productive.

Get stuff out of your head as fast as possible

This should be the focal point of any organizational system. The more rapidly you can get stuff out of your short-term memory and into a searchable database somewhere, the better organized you will be. Smart people have known this for ages.

Key Thoughts

"A reporter was out for a walk with Albert Einstein and asked for Einstein's phone number, in case there were any follow-up questions. Einstein readily agreed to give it, walked over to a pay phone, picked up the phone book, looked up his number, and read it to the reporter. In response to the reporter's astonishment, Einstein said something like,'Why remember my number, when it's in the phone book?'Yes, I doubt the story's true too. But it's funny. And it illustrates the need to get stuff out of your head so you can focus on what's important."

-Douglas Merrill

Don't even try to multitask-it's less efficient

Everyone today tries to multitask, but the human brain is just not cut out to do this. Very simply, when you multitask, you interfere with the brain's capacity to put information into short-term memory. Regardless of how you try to justify it, multitasking makes you less efficient.

To remember something, you have to transfer it from your short-term memory to your longterm memory. This is called "encoding" by cognitive scientists who study this process. Most people attempt to encode a fact by repeating it over and over-scientists call this "rehearsal." To get better organized, you need a more efficient way of doing this, because rehearsing things over and over is slow and is prone to all kinds of potential problems that crop up as well.

Use stories to remember important things

It turns out that if you associate a story with a piece of information, you stand a much improved chance of being able to recall it later on. A memorable story can act as a vivid key for retrieving facts from your longterm memory later on. This is because facts in and of themselves are usually dry and boring, whereas stories have color, action, characters, sights and emotions attached. The brain is highly proficient at remembering mental pictures that are attached to stories. Or put another way, great stories put facts into context.

Key Thoughts

"By definition, being organized requires having bits of information stored in a useful order. Putting these bits into order requires encoding them and recalling them correctly. Your brain wants to recall information not as bits and chunks, but as stories. Thus, finding ways to embed facts into stories is essential to becoming better organized."

-Douglas Merrill

If you can think ahead a little and anticipate what you'll want to do with a specific piece of information before you try to encode it into your longterm memory, you can embed that piece of information into an appropriate story. This is the ideal to work towards, although in practice you can't always forecast with precision what stories will fit your future circumstances. For now, just keep in mind that vivid stories enable later recall and give information context that makes it easier to recall that same information later on.

Look for new and better ways to get things done

In addition to the short-term memory and longterm memory transfers the human brain does, there is also one other thing brains don't like. Too many choices, whether big or small, can quickly overwhelm us and cause us to revert back to our original "default setting" choices-even if those decisions were made many years ago in entirely different circumstances.

Key Thoughts

"That's why it's so important to develop organizational systems to compensate for the limitations of our brain. The organizational methods we develop should challenge our assumptions about what we do and why we do it;emphasize the importance of filtering out what's not important and focus on what is;and take advantage of the best tools-whether they are paper or digital-for each job given the rapidly changing demands, and possibilities, of today's world. For example, I'd argue that a lot of information we've traditionally tried to store in our brains can be outsourced to the Internet."

-Douglas Merrill

Knowledge is not power-sharing knowledge is

Key Thoughts

"From an organizational standpoint, everything in our world is wrong. The way in which our work structures are organized is wrong. There's never enough time to do everything we're convinced we must do. We feel left-handed in a right-handed world. At best, we feel disorganized. At worst, defeated."

-Douglas Merrill

To illustrate:

■Why do we work 9-5 Monday to Friday in a 40-hour workweek?This came from the Industrial Revolution, when people started working in factories that had to run efficiently during set hours. So if you don't in fact work in a factory today, why do you still keep to the 40-hour workweek idea when this generates traffic gridlock and stress?

■Why do schools still have summer vacations? These were introduced so the children of farmers could help harvest crops. If you don't actually grow crops, however, wouldn't it be better to have your kids on holiday when everyone else is at school so all the places you want to go will be less crowded?

■Cars were first developed to offer people the freedom to travel wherever they wanted whenever they wanted. Why then do we all spend so much wasted time sitting in traffic jams, not to mention the problems of dependency on foreign oil and global warming?

In just the same way that society really isn't organized efficiently, the way everyone thinks about knowledge has also changed and evolved. At one time, knowledge was power. If you knew something, you had a genuine competitive advantage, and everyone was working to enrich their own "unique" know-how. But today, you'll be far more successful and less stressed as well if you share knowledge rather than trying to hoard it. A network effect comes into play. When one person knows something, he can use his best efforts to apply that knowledge. However, if you have a room full of smart people who are willing to pool and share their knowledge, what the group can achieve will be highly impressive. In today's world, it's in the sharing of knowledge that power grows exponentially rather than in the hoarding of it.

Organize around actual, not assumed constraints

All of us have constraints that are specific to us individually and that can prevent us from being organized and successful. These constraints may be:

•Physical-imposed by our actual limitations.

•Psychological-inherited from others we consider influential.

•Dictated-by society's norms.

To become better organized, you have to increase your own ability to look at constraints realistically. You need to increase your ability to figure out which of your constraints are real and which of your constraints are only assumed. It's important to know the difference so:

■You can avoid wasting time and energy attempting to overcome a constraint that isn't even real.

■You can avoid wasting time energy on things that aren't even remotely likely to yield positive results because a real constraint dictates that something is physically impossible.

Be honest with yourself but not judgmental

All of us are comparatively poor at figuring out what our actual constraints are because we're too close to the forest to see the trees. Or in other words, our constraints seem so real and final that it's hard to objectively evaluate our capacities or our environment all that realistically. This is why it's worthwhile to ask others for help in getting an objective assessment of what your real constraints are. Honest feedback on what your actual constraints are can come from people like:

•Your coworkers, peers or supervisors.

•Your boss or your subordinates who report to you.

•Your close friends, colleagues and mentors.

•Your spouse.

Know when you should ignore constraints

Once you've dug a little deeper and identified what your constraints are, you then decide which of these constraints you're going to work around and which you're going to accept at face value.

For example, regardless of how you organize your life, you'll never have more than 24 hours to work with every day or seven days in a week. Eventually, your time will run out, and that's a stone-hard certain constraint on what you will achieve. If you stress about these constraints, you won't be able to think rationally and you'll make the situations you face even worse.

Key Thoughts

"Identifying and organizing around your constraints, however, isn't without some risk. It's possible to give them too much thought and weight. Even if your constraints are real and beyond your control, that doesn't mean you should give up on the task at hand. When you do that, you don't leave space for new ideas, experiences, and outcomes. But how do you know when to ignore a constraint?You weight it against your assets, such as your skills, available resources, and the help you can get from others. You also take into consideration the risks:What's the worst thing that can happen if you ignore a constraint?When you think about it, fear is probably the biggest one we face. More often than not, fear is a constraint best ignored."

-Douglas Merrill

Know where you're going and how you'll get there

Goals are the flip side of constraints. When you have a clearly defined destination where you want to head, then you have a framework around which you can organize your information. You have criteria by which you can evaluate what's important and what's not. It becomes much easier to become better organized when you know exactly what you're trying to achieve. In fact, the more specific you are about your goals, the easier it becomes to achieve what you want, and the easier it becomes to measure your progress. The metrics you should use to evaluate your success or lack thereof also become obvious and clear.

Determining your goals generally comes down to figuring out the answers to three or four basic questions:

■What is it that I really want to achieve-at the expense of all other possibilities?

■Why do I need to achieve this?

■What will be the consequences if I do not achieve my goal?

■What are the actions I need to take to make this happen?

Be flexible about how you achieve your goals

Once you know where you want to head, it's helpful if you can also be a little bit flexible about those specific outcomes. The advantage of doing this is that if your Plan A doesn't work out quite as planned, you'll be open to finding alternative routes for achieving what you want to do.

It's also helpful if once you've thought through your goals and constraints, you pause and clear your mind before getting to work. This is a good time for both a reality check and reading what your gut instincts are telling you. The key questions you need to think about at this stage are:

•Will achieving my goal be worth all the effort I will have to put in to get there?

•Who can I delegate some of the necessary elements to?

•Who should I ask for help in achieving my goals?

When you're making big plans, there will be lots of decisions you have to make. All of us are generally not very good at making decisions for a whole range of reasons. To compensate for this, some strategies you could try are:

■Talk with someone whose opinions you value. Bounce your idea off them and ask them to identify any constraints you've over-looked. Ask them also if they can see any faulty logic you're using or personal biases that are coloring your decision. See whether or not they reinforce your decision.

■Visualize what it will be like to realize your goal. Live with that visualization for a while and decide whether it feels right.

■Do some research and gather more facts. Does additional data make your decision look better or worse?

■Make a list of the advantages and disadvantages of your idea. Prioritize your list in order of importance.

■Commit your logic to paper and leave it for a few days. Then reread what you've written and try to challenge your assumptions. Let your subconscious mind work away in the background to come p with better suggestions or to highlight drawbacks you've given too little weight to when making your initial decisions.