浮屠与佛(附英文)

“浮屠”和“佛”都是外来语。对于这两个词在中国文献中出现的先后问题是有过很大的争论的。如果问题只涉及这两个词本身,争论就没有什么必要。可是实际情况并不是这样。它涉及中印两个伟大国家文化交流的问题和《四十二章经》真伪的问题。所以就有进一步加以研究的必要。

我们都知道,释迦牟尼成了正等觉以后的名号梵文叫做Buddha。这个字是动词budh(觉)加上语尾ta构成的过去分词。在中文里有种种不同的译名:佛陀、浮陀、浮图、浮头、勃陀、勃驮、部多、部陀、毋陀、没驮、佛驮、步他、浮屠、复豆、毋驮、佛图、佛、步陀、物他、馞陀、没陀等等,都是音译。我们现在拣出其中最古的四个译名来讨论一下,就是:浮屠、浮图、复豆和佛。这四个译名可以分为两组:前三个是一组,每个都由两个字组成;第四个自成一组,只有一个字。

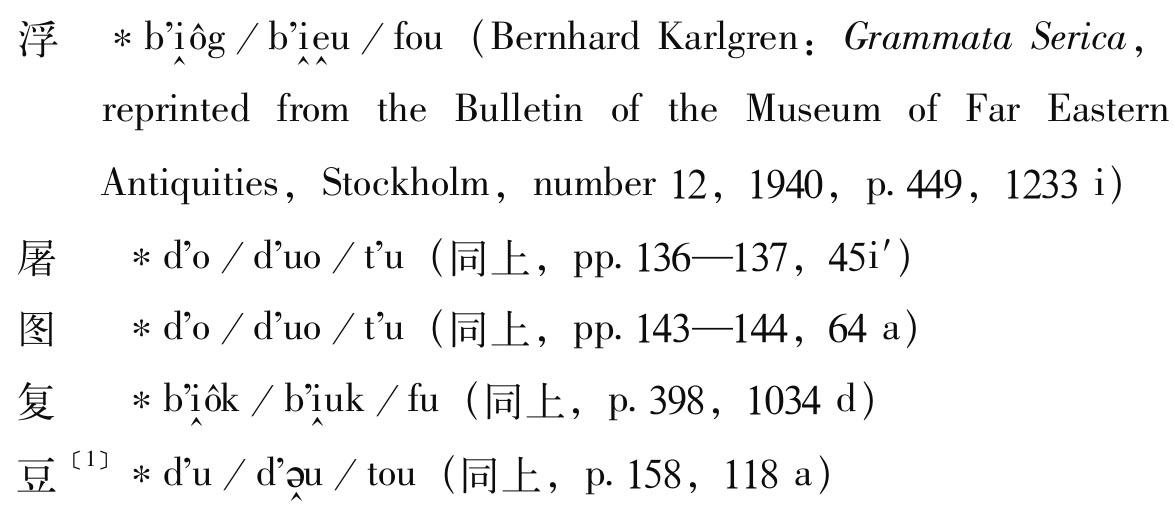

我们现在先讨论第一组。我先把瑞典学者高本汉(Bernhard Karlgren)所构拟的古音写在下面:

〔1〕鱼豢《魏略》作“复立”。《世说新语·文学篇》注作“复豆”。《酉阳杂俎》卷二《玉格》作“复立”。参阅汤用彤《汉魏两晋南北朝佛教史》上,第49页。

“浮屠”同“浮图”在古代收音都是-o,后来才转成-u;“复豆”在古代收音是-u,与梵文Buddha的收音-a都不相当。梵文Buddha,只有在体声,而且后面紧跟着的一个字第一个字母是浊音或元音a的时候,才变成Buddho。但我不相信“浮屠”同“浮图”就是从这个体声的Buddho译过来的。另外在俗语(Prākṛta)和巴利语里,Buddha的体声是Buddho。(参阅R. Pischel,Grammatik der Prakrit-Sprachen ,Grundriss der IndoArischen Philologie und Altertumskunde,Ⅰ. Band,8. Heft,Strassburg 1900,§ 363及Wilhelm Geiger,Pāli,Literatur und Sprache 同上Ⅰ. Band,7. Heft,Strassburg 1916,§ 78)在Ardhamāgadhī和Māgadhī里,阳类用-a收尾字的体声的字尾是-e,但在Ardhamāgadhī的诗歌里面有时候也可以是-o。我们现在材料不够,当然不敢确说“浮屠”同“浮图”究竟是从哪一种俗语里译过来的;但说它们是从俗语里译过来的,总不会离事实太远。

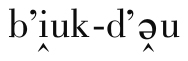

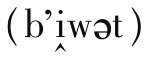

说到“复豆”,这里面有点问题。“复豆”的古音既然照高本汉的构拟应该是 ,与这相当的梵文原文似乎应该是bukdu或vukdu [1] 。但这样的字我在任何书籍和碑刻里还没见到过。我当然不敢就断定说没有,但有的可能总也不太大。只有收音的-u让我们立刻想到印度俗语之一的Apabhraṃśa,因为在Apabhraṃśa里阳类用-a收尾字的体声和业声的字尾都是-u。“复豆”的收音虽然是-u,但我不相信它会同Apabhraṃśa有什么关系。此外在印度西北部方言里,语尾-u很多,连梵文业声的-am有时候都转成-u〔参阅Hiän-lin Dschi(季羡林),Die Umwandlung der Endung -aṃ in -o und -u im Mittelindischen,Nachrichten von der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Göttingen,Philolog.-Hist. Kl. 1944,Nr. 6.〕(《印度古代语言论集》),“复豆”很可能是从印度西北部方言译过去的。

,与这相当的梵文原文似乎应该是bukdu或vukdu [1] 。但这样的字我在任何书籍和碑刻里还没见到过。我当然不敢就断定说没有,但有的可能总也不太大。只有收音的-u让我们立刻想到印度俗语之一的Apabhraṃśa,因为在Apabhraṃśa里阳类用-a收尾字的体声和业声的字尾都是-u。“复豆”的收音虽然是-u,但我不相信它会同Apabhraṃśa有什么关系。此外在印度西北部方言里,语尾-u很多,连梵文业声的-am有时候都转成-u〔参阅Hiän-lin Dschi(季羡林),Die Umwandlung der Endung -aṃ in -o und -u im Mittelindischen,Nachrichten von der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Göttingen,Philolog.-Hist. Kl. 1944,Nr. 6.〕(《印度古代语言论集》),“复豆”很可能是从印度西北部方言译过去的。

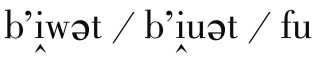

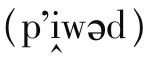

现在再来看“佛”字。高本汉曾把“佛”字的古音构拟如下:

(Grammata Serica ,p. 252,500 1)

(Grammata Serica ,p. 252,500 1)

一般的意见都认为“佛”就是“佛陀”的省略。《宗轮论述记》说:“‘佛陀’梵音,此云觉者。随旧略语,但称曰‘佛’。”佛教字典也都这样写,譬如说织田得能《佛教大辞典》页一五五一上;望月信亨《佛教大辞典》页四四三六上。这仿佛已经成了定说,似乎从来没有人怀疑过。这说法当然也似乎有道理,因为名词略写在中文里确是常见的,譬如把司马长卿省成马卿,司马迁省成马迁,诸葛亮省成葛亮。尤其是外国译名更容易有这现象。英格兰省为英国,德意志省为德国,法兰西省为法国,美利坚省为美国,这都是大家知道的。

但倘若仔细一想,我们就会觉得这里面还有问题,事情还不会就这样简单。我们观察世界任何语言里面外来的假借字(Loanwords,Lehnwörter),都可以看出一个共同的现象:一个字,尤其是音译的,初借过来的时候,大半都多少还保留了原来的音形,同本地土产的字在一块总是格格不入。谁看了也立刻就可以知道这是“外来户”。以后时间久了,才渐渐改变了原来的形式,同本地的字同化起来,终于让人忘记了它本来不是“国货”。这里面人们主观的感觉当然也有作用,因为无论什么东西,看久了惯了,就不会再觉得生疏。但假借字本身的改变却仍然是主要原因。“佛”这一个名词是随了佛教从印度流传到中国来的。初到中国的时候,译经的佛教信徒们一定想完全保留原字的音调,不会就想到按了中国的老规矩把一个有两个音节的字缩成一个音节,用一个中国字表示出来。况且Buddha这一个字对佛教信徒是何等尊严神圣,他们未必在初期就有勇气来把它腰斩。

所以我们只是揣情度理也可以想到“佛”这一个字不会是略写。现在我们还有事实的证明。我因为想研究另外一个问题,把后汉三国时代所有的译过来的佛经里面的音译名词都搜集在一起,其中有许多名词以前都认为是省略的。但现在据我个人的看法,这种意见是不对的。以前人们都认为这些佛经的原本就是梵文。他们拿梵文来同这些音译名词一对,发现它们不相当,于是就只好说,这是省略。连玄奘在《大唐西域记》里也犯了同样的错误,他说这个是“讹也”,那个是“讹也”,其实都不见得真是“讹也”。现在我们知道,初期中译佛经大半不是直接由梵文译过来的,拿梵文作标准来衡量这里面的音译名词当然不适合了。这问题我想另写一篇文章讨论,这里不再赘述。我现在只把“佛”字选出来讨论一下。

“佛”字梵文原文是Buddha,我们上面已经说过。在焉耆文(吐火罗文A)里Buddha变成Ptākät。这个字有好几种不同的写法:Ptāñkät,Ptāñkte,Ptāṃñkte,Ptāñäkte,Ptāñikte,Ptāññäkte,Pättāñäkte,Pättāññäkte,Pättāñkte,Pättāṃñkte,Pättāṃñäkte。(参阅Emil Sieg,Wilhelm Siegling und Wilhelm Schulze,Tocharische Grammatik ,Göttingen 1931,§76,116,122a,123,152b,192,206,207,363c)这个字是两个字组成的,第一部分是ptā-,第二部分是-ñkät。ptā相当梵文的Buddha,可以说是Buddha的变形。因为吐火罗文里面浊音的b很少,所以开头的b就变成了p。第二部分的ñkät是“神”的意思,古人译为“天”,相当梵文的deva。这个组合字全译应该是“佛天”。“天”是用来形容“佛”的,说了“佛”还不够,再给它加上一个尊衔。在焉耆文里,只要是梵文Buddha,就译为Ptāñkät。在中文《大藏经》里,虽然也有时候称佛为“天中天(或王)”(devātideva) [2] ,譬如《妙法莲华经》卷三,《化城喻品》七:

圣主天中王

迦陵频伽声

哀愍众生者

我等今敬礼〔《大正新修大藏经》(下面缩写为),9,23c〕

与这相当的梵文是:

namo'stu te apratimā maharṣe devātidevā kalavīṅkasusvarā|

vināyakā loki sadevakasminvandāmi te lokahitānukampī‖

(Saddharmapuṇḍarīka,edited by H. Kern and Bunyiu Nanjio,Bibliotheca Buddhica X,St.-Pétersbourg 1912,p. 169,L. 12、13)

但“佛”同“天”连在一起用似乎还没见过。在梵文原文的佛经里面,也没有找到Buddhadeva这样的名词。但是吐火罗文究竟从哪里取来的呢?我现在还不能回答这问题,我只知道,在回纥文(Uigurisch)的佛经里也有类似的名词,譬如说在回纥文译的《金光明最胜王经》(Suvarṇaprabhāsottamarājasūtra )里,我们常遇到tngri tngrisi burxan几个字,意思就是“神中之神的佛”,与这相当的中译本里在这地方只有一个“佛”字。(参阅F. W. K. Müller,Uigurica ,Abhandlungen der Königl. Preuss. Akademie der Wissenschaften,1908,pp. 28、29等;UiguricaⅡ,Berlin 1911,p. 16等)两者之间一定有密切的关系,也许是抄袭假借,也许二者同出一源;至于究竟怎样,目前还不敢说。

我们现在再回到本题。在ptāñkät这个组合字里,表面上看起来,第一部分似乎应该就是ptā-。但实际上却不然。在焉耆文里,只要两个字组合成一个新字的时候,倘若第一个字的最后一个字母不是a,就往往有一个a加进来,加到两个字中间。譬如aträ同tampe合起来就成了atra-tampe,kāsu同ortum合起来就成了kāswaortum,kälp同pälskāṃ合起来就成了kälpapälskāṃ,pär同krase合起来就成了pärrakrase,pältsäk同pāṣe合起来就成了pälskapaṣe,prākār同pratim合起来就成了prākra-pratim,brāhmaṃ同purohitune合起来就成了brähmna-purohitune,ṣpät同koṃ合起来就成了säpta-koñi。(参阅Emil Sieg,Wilhelm Siegling und Wilhelm Schulze,Tocharische Grammatik ,§363,a)中间这个a有时候可以变长。譬如wäs同yok合起来就成了wsā-yok,wäl同ñkät合起来就成了wlā-ñkät。(同上,§363,c)依此类推,我们可以知道ptā的原字应该是pät;据我的意思,这个pät还清清楚楚地保留在ptāñkät的另一个写法pättāñkät里。就现在所发掘出来的残卷来看,pät这个字似乎没有单独用过。但是就上面所举出的那些例子来看,我们毫无可疑地可以构拟出这样一个字来的。我还疑心,这里这个元音没有什么作用,它只是代表一个更古的元音u。

说ä代表一个更古的元音u,不是一个毫无依据的假设,我们有事实证明。在龟兹文(吐火罗文B),与焉耆文Ptāñkät相当的字是Pūdñäkte。〔Pudñäkte,pudñikte,见Sylvain Lévi,Fragments des Textes Koutchéens ,Paris 1933:Udānavarga,(5)a 2;Udānālaṃkara,(1)a 3;b 1,4;(4)a 4;b 1,3;Karmavibhaṇga,(3)b 1;(8)a 2,3;(9)a 4;b 1,4;(10)al;(11)b 3〕我们毫无疑问地可以把这个组合字分拆开来,第一个字是pūd或pud,第二个字是ñäkte。pūd或pud就正相当焉耆文的pät。在许多地方吐火罗文B(龟兹文)都显出比吐火罗文A(焉耆文)老,所以由pūd或pud变成pät,再由pät演变成ptā,这个过程虽然是我们构拟的,但一点也不牵强,我相信,这不会离事实太远。

上面绕的弯子似乎有点太大了,但实际上却一步也没有离开本题。我只是想证明:梵文的Buddha,到了龟兹文变成了pūd或pud,到了焉耆文变成了pät,而我们中文里面的“佛”字就是从pūd、pud(或pät)译过来的。“佛”并不是像一般人相信的是“佛陀”的省略。再就后汉三国时的文献来看,“佛”这个名词的成立,实在先于“佛陀”。在“佛”这一名词出现以前,我们没找到“佛陀”这个名词。所以我们毋宁说,“佛陀”是“佛”的加长,不能说“佛”是“佛陀”的省略。

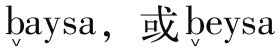

但这里有一个很重要的问题:“佛”字古音but是浊音,吐火罗文的pūd、pud或pät都是清音。为什么中文佛典的译者会用一个浊音来译一个外来的清音?这个问题倘不能解决,似乎就要影响到我们整个的论断。有的人或者会说:“佛”这个名词的来源大概不是吐火罗文,而是另外一种浊音较多的古代西域语言。我以为,这怀疑根本不能成立。在我们截止到现在所发现的古代西域语言里,与梵文Buddha相当的字没有一个可以是中文“佛”字的来源的。在康居语里,梵文Buddha变成pwty或pwtty(见Robert Gauthiot,Le Sūtra du religieux Ongles-Longs ,Paris 1912,p. 3)。在于阗语里,早期的经典用balysa来译梵文的Buddha和Bhagavat,较晚的经典里,用 。(见Sten Konow,Saka Studies ,Oslo Etnografiske Museum Bulletin 5,Oslo 1932,p. 121;A. F. Rudolf Hoernle,Manuscript Remains of Buddhist Literature Found in Eastern Turkestan ,Vol. 1,Oxford 1916,pp. 239、242)。至于组合字(samāsa)像buddhakṣetra则往往保留原字。只有回纥文的佛经曾借用过一个梵文字bud,似乎与我们的“佛”字有关。在回纥文里,通常是用burxan这个字来译梵文的Buddha。但在《金光明最胜王经》的译本里,在本文上面有一行梵文:

。(见Sten Konow,Saka Studies ,Oslo Etnografiske Museum Bulletin 5,Oslo 1932,p. 121;A. F. Rudolf Hoernle,Manuscript Remains of Buddhist Literature Found in Eastern Turkestan ,Vol. 1,Oxford 1916,pp. 239、242)。至于组合字(samāsa)像buddhakṣetra则往往保留原字。只有回纥文的佛经曾借用过一个梵文字bud,似乎与我们的“佛”字有关。在回纥文里,通常是用burxan这个字来译梵文的Buddha。但在《金光明最胜王经》的译本里,在本文上面有一行梵文:

Namo bud o o namo drm o o namo sang

(F. W. K. Müller,Uigurica,1908,p. 11)

正式的梵文应该是:

Namo buddhāya o o namo dharmāya o o namaḥ saṅghāya。

在这部译经里常有taising和sivsing的字样。taising就是中文的“大乘”,sivsing就是中文的“小乘”。所以这部经大概是从中文译过去的。但namo bud o o namo drm o o namo sang这一行却是梵文,而且像是经过俗语借过去的。为什么梵文的Buddha会变成bud,这我有点说不上来。无论如何,这个bud似乎可能就是中文“佛”字的来源。但这部回纥文的佛经译成的时代无论怎样不会早于唐代,与“佛”这个名词成立的时代相差太远,“佛”字绝没有从这个bud译过来的可能。我们只能推测,bud这样一个字大概很早很早的时候就流行在从印度传到中亚去的俗语里和古西域语言里。它同焉耆文的pät,龟兹文的pūd和pud,可能有点关系。至于什么样的关系,目前文献不足,只有阙疑了。

除了以上说到的以外,我们还可以找出许多例证,证明最初的中译佛经里面有许多音译和意译的字都是从吐火罗文译过来的。所以,“佛”这一个名词的来源也只有到吐火罗文的pät、pūt和pud里面去找。

写到这里,只说明了“佛”这名词的来源一定是吐火罗文。但问题并没有解决。为什么吐火罗文里面的清音,到了中文里会变成浊音?我们可以怀疑吐火罗文里辅音p的音值。我们知道,吐火罗文的残卷是用Brāhmī字母写的。Brāhmī字母到了中亚在发音上多少有点改变。但只就p说,它仍然是纯粹的清音。它的音值不容我们怀疑。要解决这问题,只有从中文“佛”字下手。我们现在应该抛开高本汉构拟的“佛”字的古音,另外再到古书里去找材料,看看“佛”字的古音还有别的可能没有:

《毛诗·周颂·敬之》:“佛时仔肩。”《释文》:“佛,毛符弗反郑音弼。”

《礼记·曲礼》上:“献鸟者佛其首。”《释文》佛作拂,云:“本又作佛,扶弗反,戾也。”

《礼记·学记》:“其施之也悖,其求之也佛。”《释文》:“悖,布内反;佛,本又作拂,扶弗反。”

〔案《广韵》,佛,符弗切,拂,敷勿切

。〕

上面举的例子都同高本汉所构拟的古音一致。但除了那些例子以外,还有另外一个“佛”:

《仪礼·既夕礼》郑注:“执之以接神,为有所拂也”。《释文》:“拂

,本又作佛仿;上芳味反;下芳丈反。”

《礼记·祭义》郑注:“言想见其仿佛来。”《释文》:“仿,孚往反;佛,孚味反。”

《史记·司马相如传》《子虚赋》:“缥乎忽忽,若神仙之仿佛。”(《汉书》、《文选》改为髣髴)

《汉书·扬雄传》:“犹仿佛其若梦。”注:“仿佛即髣髴字也。”

《汉书·李寻传》:“察其所言,仿佛一端。”师古曰:“仿读曰髣,佛与髴同。”

《后汉书·仲长统传》:“呼吸精和,求至人之仿佛。”

《淮南子·原道》:“叫呼仿佛,默然自得。”

《文选》潘岳《寡妇赋》:“目仿佛乎平素。”李善引《字林》曰:“仿,相似也;佛,不审也。”

玄应《一切经音文》:“仿佛,声类作髣髴同。芳往敷物二反。”

《玉篇》:“佛,孚勿切。”《万象名义》:“佛,芳未反。”

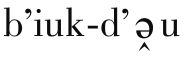

从上面引的例子看起来,“佛”字有两读。“佛”古韵为脂部字,脂部的入声韵尾收t,其与入声发生关系之去声,则收d。“佛”字读音,一读入声,一读去声:(一)扶弗反 ;(二)芳味反或孚味反

;(二)芳味反或孚味反 。现在吐火罗文的pūd或pud与芳味反或孚味反正相当。然则,以“佛”译pūd正取其去声一读,声与韵无不吻合。

。现在吐火罗文的pūd或pud与芳味反或孚味反正相当。然则,以“佛”译pūd正取其去声一读,声与韵无不吻合。

把上面写的归纳起来,我们可以得到下面的结论:“浮屠”、“浮图”、“复豆”和“佛”不是一个来源。“浮屠”、“浮图”、“复豆”的来源是一种印度古代方言。“佛”的来源是吐火罗文。这结论看来很简单;但倘若由此推论下去,对佛教入华的过程,我们可以得到一点新启示。

在中国史上,佛教输入中国可以说是一件很有影响的事情。中国过去的历史书里关于这方面的记载虽然很不少,但牴牾的地方也很多(参阅汤用彤《汉魏两晋南北朝佛教史》上,第1—15页),我们读了,很难得到一个明确的概念。自从19世纪末年20世纪初年欧洲学者在中亚探险发掘以后,对这方面的研究有了很大的进步,简直可以说是开了一个新纪元。根据他们发掘出来的古代文献器物,他们向许多方面作了新的探讨,范围之大,史无前例。对中国历史和佛教入华的过程,他们也有了很大的贡献。法国学者烈维(Sylvain Lévi)发现最早汉译佛经所用的术语多半不是直接由梵文译过来的,而是间接经过一个媒介。他因而推论到佛教最初不是直接由印度传到中国来的,而是间接由西域传来。(参阅Sylvain Lévi,Le《Tokharien B》Langue de Koutcha ,Journal Asiatique 1913,Sept.-Oct. pp. 311—338。此文冯承钧译为中文:《所谓乙种吐火罗语即龟兹国语考》,载《女师大学术季刊》,第一卷,第四期。同期方壮猷《三种古西域语之发见及其考释》,有的地方也取材于此文。)这种记载,中国书里当然也有;但没有说得这样清楚。他这样一说,我们对佛教入华的过程最少得到一个清楚的概念。一直到现在,学者也都承认这说法,没有人说过反对或修正的话。

我们上面说到“佛”这名词不是由梵文译来的,而是间接经过龟兹文的pūd或pud(或焉耆文的pät)。这当然更可以助成烈维的说法,但比“佛”更古的“浮屠”却没有经过古西域语言的媒介,而是直接由印度方言译过来的。这应该怎样解释呢?烈维的说法似乎有修正的必要了。

根据上面这些事实,我觉得,我们可以作下面的推测:中国同佛教最初发生关系,我们虽然不能确定究竟在什么时候,但一定很早 [3] (参阅汤用彤《汉魏两晋南北朝佛教史》上,第22页),而且据我的看法,还是直接的;换句话说,就是还没经过西域小国的媒介。我的意思并不是说,佛教从印度飞到中国来的。它可能是先从海道来的,也可能是从陆路来的。即便从陆路经过中亚小国而到中国,这些小国最初还没有什么作用,只是佛教到中国来的过路而已。当时很可能已经有了直接从印度俗语译过来的经典。《四十二章经》大概就是其中之一。“浮屠”这一名词的形成一定就在这时候。这问题我们留到下面再讨论。到了汉末三国时候,西域许多小国的高僧和居士都到中国来传教,像安士高、支谦、支娄迦谶、安玄、支曜、康巨、康孟详等是其中最有名的。到了这时候,西域小国对佛教入华才真正有了影响。这些高僧居士译出的经很多。现在推测起来,他们根据的本子一定不会是梵文原文,而是他们本国的语言。“佛”这一名词的成立一定就在这时期。

现在我们再回到在篇首所提到的《四十二章经》真伪的问题。关于《四十二章经》,汤用彤先生已经论得很精到详明,用不着我再来作蛇足了。我在这里只想提出一点来讨论一下,就是汤先生所推测的《四十二章经》有前后两个译本的问题。汤先生说:

现存经本,文辞优美,不似汉译人所能。则疑旧日此经,固有二译。其一汉译,文极朴质,早已亡失。其一吴支谦译,行文优美,因得流传。(《汉魏两晋南北朝佛教史》上,第36页)

据我自己的看法,也觉得这个解释很合理。不过其中有一个问题,以前我们没法解决,现在我们最少可以有一个合理的推测了。襄楷上桓帝疏说:

浮屠不三宿桑下,不欲久,生恩爱,精之至也。天神遗以好女,浮屠曰:“此但革囊盛血。”遂不盼之。其守一如此。(《后汉书》卷六十下)

《四十二章经》里面也有差不多相同的句子:

日中一食,树下一宿,慎不再矣。使人愚蔽者,爱与欲也。(17,722b)

天神献玉女于佛,欲以试佛意、观佛道。佛言:“革囊众秽,尔来何为?以可诳俗,难动六通。去,我不用尔!”(17,723b)

我们一比较,就可以看出来,襄楷所引很可能即出于《四十二章经》。汤用彤先生(《汉魏两晋南北朝佛教史》上,第33—34页)就这样主张。陈援庵先生却怀疑这说法。他说:

树下一宿,革囊盛秽,本佛家之常谈。襄楷所引,未必即出于《四十二章经》。

他还引了一个看起来很坚实的证据,就是襄楷上书用“浮屠”两字,而《四十二章经》却用“佛”。这证据,初看起来,当然很有力。汤先生也说:

旧日典籍,唯借钞传。“浮屠”等名,或嫌失真,或含贬辞。后世展转相录,渐易旧名为新语。(《汉魏两晋南北朝佛教史》上,第36页)

我们现在既然知道了“浮屠”的来源是印度古代俗语,而“佛”的来源是吐火罗文,对这问题也可以有一个新看法了。我们现在可以大胆地猜想:《四十二章经》有两个译本。第一个译本,就是汉译本,是直接译自印度古代俗语。里面凡是称“佛”,都言“浮屠”。襄楷所引的就是这个译本。但这里有一个问题:中国历史书里,关于佛教入华的记载虽然有不少牴牾的地方,但是《理惑论》里的“于大月支写佛经四十二章”的记载却大概是很可靠的。既然这部《四十二章经》是在大月支写的,而且后来从大月支传到中国来的佛经原文都不是印度梵文或俗语,为什么这书的原文独独会是印度俗语呢?据我的推测,这部书从印度传到大月支,他们还没来得及译成自己的语言,就给中国使者写了来。一百多年以后,从印度来的佛经都已经译成了本国的语言,那些高僧们才把这些译本转译成中文。第二个译本就是支谦的译本,也就是现存的。这译本据猜想应该是译自某一种中亚语言。至于究竟是哪一种,现在还不能说。无论如何,这个译文的原文同第一个译本不同;所以在第一个译本里称“浮屠”,第二个译本里称“佛”,不一定就是改易的。

根据上面的论述,对于“佛”与“浮屠”这两个词,我们可以作以下的推测:“浮屠”这名称从印度译过来以后,大概就为一般人所采用。当时中国史家记载多半都用“浮屠”。其后西域高僧到中国来译经,才把“佛”这个名词带进来。范蔚宗搜集的史料内所以没有“佛”字,就因为这些史料都是外书。“佛”这名词在那时候还只限于由吐火罗文译过来的经典中。以后才渐渐传播开来,为一般佛徒,或与佛教接近的学者所采用。最后终于因为它本身有优越的条件,战胜了“浮屠”,并取而代之。

附记:

写此文时,承周燕孙先生帮助我解决了“佛”字古音的问题。我在这里谨向周先生致谢。

1947年10月9日

注释:

[1] 参阅Pelliot,Meou-Tseu ou les doutes levés,T'oung Pao (《通报》)Vol. XIX,1920,p. 430.

[2] 参阅《释氏要览》中, 54,284b—c。

54,284b—c。

[3] 《魏书·释老志》说:“及开西域,遣张骞使大夏。还,传其旁有身毒国,一名天竺。始闻浮屠之教。”据汤先生的意思,这最后一句,是魏收臆测之辞;因为《后汉书·西域传》说:“至于佛道神化,兴自身毒;而二汉方志,莫有称焉。张骞但著地多暑湿,乘象而战。”据我看,张骞大概没有闻浮屠之教。但在另一方面,我们仔细研究魏收处置史料的方法,我们就可以看出,只要原来史料里用“浮屠”,他就用“浮屠”;原来是“佛”,他也用“佛”;自叙则纯用“佛”。根据这原则,我们再看关于张骞那一段,就觉得里面还有问题。倘若是魏收臆测之辞,他不应该用“浮屠”两字,应该用“佛”。所以我们虽然不能知道他根据的是什么材料,但他一定有所本的。

附:

On the Oldest Chinese Transliterations of the Name of Buddha

In the year 1933 Dr. Hu Shih wrote an article entitled“On the Sūtra of the 42 Sections”(Hu Shih lun shue kin cho ,1,2,pp. 177—186)in the order to discuss the authenticity of the Sūtra. In this article,just at the beginning,he discussed the probable dates when the two transliterations Fou-t'u(浮屠)and Fo(佛)came to be used in China. Prof. Chen Yuan then communicated his views on the transliterations in some letters to Dr. Hu Shih. They were agreed only on one point that Fou-t'u came to be used earlier than Fo. On several other points their opinions differ specially when Prof. Chen says:“Fo is not mentioned in the historical materials of the Latter Han dynasty collected by Fan Wei-tsong”(ibid. p. 179). He further says—“In the decrees of and the memorials to the Emperors of the Latter Han dynasty only Fou-tu is used and not Fo. This I have told you in my last letter. A chapter on India is quoted in the commentary on the San kuo che by Pei Sung chih. In this chapter the word Fou-tu occurs eight times and there is no mention of Fo. Twice there is mention of Fou-t'u-king and not of Fo-king . Chen Shou uses Fou-t'u and Fo at the same time. Yuan Hung uses only Fo and explains Fou-t'u by Fo. Fan Wei-tsong retains in the decrees and memorials quoted by him the name Fou-t'u and uses Fo when he writes himself(ibid,p. 189).

From the study of the historical materials already mentioned Prof. Chen draws the following conclusions:(ⅰ)From the Latter Han to the middle of Wei period only Fou-t'u is used;(ⅱ)From the period of the Three Kingdoms to the beginning of the Tsin Fou-t'u and Fo are simultaneously used;(ⅲ)From the Eastern Tsin to the Song period only Fo is used. In the light of these deductions he draws the further conclusion that the Li-hui-lun of Mou Tseu and all the Han translations of the Buddhist texts cannot be treated as really written and translated in the Han period(ibid. p. 190). Dr. Hu Shih however does not agree with the view that Fo does not occur in the historical materials of the Han period collected by Fan Wei-tsong.

I propose here to discuss the problem from a quite different point of view. Dr. Hu and Prof. Chen have tried to find out the probable dates of the first use of the two forms of the name. I shall try to trace the origin of the two forms of the name. If we can trace their origin clearly it will throw some light on the problem raised by Dr. Hu and Prof. Chen.

We know that S′ākyamuni came to be known as Buddha after his attainment of Samyak Sambodhi. The word Buddha means“the illumined”. In Chinese there are more than 20 different transliterations of this name:Fo-t'o,Fou-t'o,Fou-t'u,Feu-t'ou,Pu-t'o,Pu-ta,Pu-to,Pu-t'o,Mu-t'o,Mei-ta,Fo-ta,Pu-t'a,Fou-t'u,Fu-tou,Mu-ta,Fo-t'u,Fo,Pu-t'o,Wu-t'a,Pu-t'o,Mei-t'o etc.*

I will confine my discussion to the four oldest of these transliterations namely:Fou-t'u,Fou-t'u,Fu-tou and Fo. The first three belong to the same group each consisting of two words while the fourth belong to a different group of only one word.

Let us consider the first group. The ancient pronunciation of the words occurring in this group according to the reconstruction of Karlgren are the following(Grammata Serica ,reprinted from the Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities,Stockholm,no. 12,1940):

浮 [1] b'iôg/b'iəu/fou(449,1233i)

屠[2] d'o/d'uo/t'u(136-137,45 i')

图[3] d'o/d'uo/t'u(143-144,63a)

复[4] b'iôk/b'iuk/fu(398,1034d)

豆 [5]  (158,118a)

(158,118a)

The final vowel in both Fou-t'u and Fou-t'u was in ancient pronunciation -o-,it became later -u-;Fu-tou had a final -u-in ancient times. None of them correspond to Sanskrit Buddha . In Sanskrit Buddha becomes Buddho only in the nominative case when the following word begins with a sonant or with the vowel -a-. But I do not believe that Chinese Fou-t'u and Fou-t'u came from the nominative Buddho. In Prakrit and Pali the nominative of Buddha is Buddho. In ArdhaMāgadhī and Māgadhī,the masculine bases in -a-have -e-in the nominative,but in ArdhaMāgadhī verses it is sometimes found with an ending in -o-. But we have not sufficient materials to say from which Prakrit Fou-t'u and Fou-t'u came. We are however justified in assuming that they were based on some Prakrit forms.

As to Fu-tou the problem is somewhat complicated. Since the old pronunciation,according to Karlgren,was  ,the corresponding Indian form would be bukdu or vukdu . But this form is not found either in old texts or inscriptions. The final -u-reminds us of Apabhraṃśa because in Apabhraṃśa the masculine -a-bases have -u-in nominative and accusative. But in spite of the -u-it does not seem to have been an Apabhraṃśa form. In the NorthWestern dialect of India the ending -u-is common,even the accusative ending of Sanskrit -am and Prakrit -aṃbecome at times -u-(cf. my article Die Umwandlung der Endung -aṃ in -o und -u im Mittelindischen,Nachrichten Ak. Wiss. Göttingen,PhiloHist. Kl. 1944,nr. 6). The name Fu-tou most probably comes from this Prakrit.

,the corresponding Indian form would be bukdu or vukdu . But this form is not found either in old texts or inscriptions. The final -u-reminds us of Apabhraṃśa because in Apabhraṃśa the masculine -a-bases have -u-in nominative and accusative. But in spite of the -u-it does not seem to have been an Apabhraṃśa form. In the NorthWestern dialect of India the ending -u-is common,even the accusative ending of Sanskrit -am and Prakrit -aṃbecome at times -u-(cf. my article Die Umwandlung der Endung -aṃ in -o und -u im Mittelindischen,Nachrichten Ak. Wiss. Göttingen,PhiloHist. Kl. 1944,nr. 6). The name Fu-tou most probably comes from this Prakrit.

Let us now discuss the form Fo. Karlgren reconstructs the old pronunciation as b'iwət/b'iuət/fu(Grammata Serica 252,500 1). Usually the word Fo is considered to be an abridgement of the word Fo-t'o. In the Tsong Liun lun shu ki it is said“Fo-t'o is a Sanskrit word;in Chinese it means kio-che‘the awakened’;we follow the old abridgement and call it Fo.”In the Buddhist dictionaries we find the same explanation of Fo(cf. ‘Bukkyo daijiten ’,p. 155). This seems to have been the explanation as established by tradition. The explanation seems to be reasonable at the first sight for in Chinese such abridgements are common.

But if we go deeper into the problem then we find that such an explanation is unsatisfactory. A study of loan words in other languages points out to a common rule. When a word is introduced from another language it retains mostly the original form at the beginning. It then does not get mixed up with the native words. Gradually it changes its original form and is mixed up with the native words. The name of Buddha came to China with Buddhism from India. When it first came to China the translators would surely retain the original form of the name. They would not use an abbreviation from the beginning. Moreover the name of Buddha was a sacred name for the Buddhists. They would not venture to alter it.

Under these circumstances it is more reasonable to assume that the word Fo is not an abridgement. There is further evidence to confirm it. I have collected all the transliterations in the translations of the Latter Han period and of the period of the Three Kingdoms. Some of the transliterations formerly considered to be abridgements do not appear to me to be so. The words in transliterations used to be formerly compared with original Sanskrit words as it was believed that the texts had been translated from Sanskrit original. As the transliterations were found not corresponding with the Sanskrit they were explained as abbreviations. Even Hiuantsang in his Ta t'ang si yu ki makes that mistake. We now know that most of the oldest Buddhist translations were not based on Sanskrit. So the old transliterations should not be compared with Sanskrit forms. As I propose to deal with the problem in another article I will confine my attention here to the discussion of the word Fo.

The Sanskrit word for Fo,we have seen,is Buddha. The word Buddha becomes in Tokharian A ptañkat and is written in different ways such as:ptāñkat,ptāñkte,ptāṃñkte,ptāñakte,ptāñäkte,ptāñikte,ptāññakte,pättāñakte,pättāññakte,pättāñkte,pättāṃñkte,pättāṃñkte(cf. Sieg,Siegling,Schulze Tocharische Grammatik ,§76,116,122a,123,152b,192,206,207,363c). The word ptāñkat is a combination of two words ptā and ñkat. Ptā corresponds to Sanskrit Buddha. In Tokharian the sonants are rare. Therefore the initial -b-changes into -p-. The second part -ñkat means“god”and thus stands for Sanskrit -deva. The word ptāñkat therefore may be translated as Fo-t'ien i.e. Buddhadeva. In Tokharian A the Sanskrit word Buddha is always translated as ptāñkat. In the Chinese Tripit·aka we find the terms t'ien chong wang (天中王)in the translation of the Saddharmapuṇḍarika where they stand for Sanskrit devātideva . cf. the Sanskrit text,ed. Kern. Nanjio,p. 169,L. 12-13:

namo'stu te apratimā maharṣe devātideva kalavinkasusvarā/

vināyakā loki sadevakasminvandāmi te lokahitānukampī//

But the term Fo-t'ien is never found in the Chinese Buddhist texts. Neither is the term‘Buddhadeva’found in Sanskrit texts. From which source did then the Tokharian borrow this word?This question cannot be answered now. A similar term is found in the Uigur translations of the Buddhist texts. cf. the Uigur translation of the Suvarṇaprabhāsa-sūtra(Müller,Uigurica,A. K. A. W.,1908,p. 28ff. UiguricaⅡ,1911,p. 16):tngri tngrisi burxan “Buddha,the god of gods”. A comparison of the Uigur and Tokharian names of Buddha shows either that the former was derived from the latter or that both go back to the same origin which might probably have been Iranian.

In the compound ptāñkät the first part seems to be ptā,but in fact it is not quite so. In the Tokharian A when two words are compounded an -a-is inserted after the first part if it does not end in an -a. cf. aträ+tampe=atra-tampe,kāsu+ortum=kāswaortum,kälp+pälskāṃ=kälpapälskāṃ,pär+krase=pärrakrase,pältsäk+pāṣe=pälskapāṣe,prākär+pratim=prākra-pratim,brāhmaṃ+purohitum=brāhmna-purohitum,ṣpät+koṃ=ṣäpta-koñi(Tocharische Grammatik ,§363a). The -a-may be sometimes lengthened as in wäs+yok=wsā-yok,wäl+ñkät=wlāñkät(ibid 363 c). From these examples we can infer that ptā was originally pät. The word pät is clearly preserved in the compound pättañkät which is another form of ptāñkät. In the manuscripts we have not yet found an independent pät. But its existence cannot be doubted. It may be further assumed that the vowel -ä-stands here for an older -u-.

The hypothesis that the vowel -ä.stands for an older -u-can be proved from Kuchean. The corresponding word for Tokharian ptāñkät in Kuchean is pūdñäkte pudñäkte,pudñikte(cf. Lévi,Fragments des textes Koutcheens ,Paris,1933,p. 139). The word may be analysed with certainty as pūd/pud+ñäkte.pūd/pud corresponds with Tokharian pät. In some respects the Kuchean is older than Tokharian. Therefore the change from pūd/pud to pät/ptā is quite natural.

So far we have indulged in a digression from our main point. It may be however shown that Sanskrit Buddha becomes in Kuchean pūd/pud and in Tokharian Pät and that the Chinese Fo is a transliteration from Kuchean. Thus Fo is not an abridgement of Fo-t'o as hitherto believed. In the texts of the Latter Han and the Three Kingdoms it is the word Fo which is used first. Fo-t'o is not yet mentioned. Therefore we should say that Fo-t'o is a later lengthening of Fo and not that Fo is an abridgement.

The hypothesis however raises an important question. The old pronunciation of Fo starts with a sonant‘But ’. In Kuchean pūd/pud it is a surd. Why do the Chinese Buddhist texts render a surd by a sonant?Unless this question is satisfactorily answered our hypothesis cannot become a proof. It might be argued that Chinese Fo is not based on the Kuchean but on some other Central Asian form. In Sogdian Sanskrit Buddha is rendered as pwty pwtty(Gauthiot,Le Sūtra du religicux Ongles-Longs ,p. 3). In older Khotanese the word is balysa for‘Buddha Bhagavat’. In later Khotanese it is baysa,beysa,biysa(Sten Konow,Saka Studies ,Oslo Etnografiske Museum Bulletin,5,p. 121,Hoernle,Manuscript Remains …,I pp. 239,242). In Uigur‘Burxan’is the common translation of Sanskrit Buddha. But in the Uigur translation of the Suvarṇ aprabhāsa-Sūtra(Müller,Uigurica p. 11)we find‘namo bud…namo drm…namo sang' which correspond to Sanskrit‘namo buddhāya…namo dharmāya…namo saṇghāya.’In this Uigur translation we find the words taising and sivsing which are really Chinese ta chèng and hsiao cheng . The occurrence of these words shows that the text was translated from Chinese. But the line‘namo bud…etc.’,comes directly from Indian source. Why the Sanskrit word becomes Bud in Uigur cannot be explained. Anyhow the Uigur Bud might be the source of Chinese Fo if there had not been a chronological difficulty. The Uigur translation is not older than the T'ang period but Fo goes back to the Han. Fo therefore could not have been derived from Uigur.

There are many other evidences to show that the oldest Chinese Buddhist translations and transliterations were based on Tokharian and Kuchean. The Chinese Fo could have only been derived from these two sources.

Till now I have tried to show only that the source of Chinese name is Tokharian or Kuchean but the problem that a Kuchean sonant becomes a surd in Chinese remains unsolved. The only way of solving the problem is to reexamine the old pronunciation of Fo. The old pronunciation as reconstructed by Karlgren is bud . But besides this Fo there was another Fo. The character is the same but the pronunciations are different. cf. Li Ki ,chap. chi yi,comm.of Cheng…“(言想见其仿佛来)”. She-wen gives the pronunciation of fang(仿)as(浮往反)and of fo as浮味反(p'iwəd). There are also other instances of this pronunciation of Fo in Yi-li,chap. Chi hsi li,She-ki etc.

From these examples we can find that the word Fo had two pronunciations. In the ancient Chinese phonetic system the word Fo belongs to the group(脂)the final of ju sheng of the che group is t ;the kiusheng related to ju-sheng has a final d . Therefore Fo is pronounced in two ways:(ⅰ)ju-sheng -b'iwət and(ⅱ)kiusheng -p'iwəd. The Kuchean pud-pūd exactly correspond with the kiusheng of Fo in initial and final.

We may therefore conclude that Fou-t'u. Fou-t'u,Fu-tou,and Fo are of different sources. The first three come from an Indian Prakrit and the last come through Kuchean. The conclusion seems to be very simple but it throws some new light on the history of the introduction of Buddhism in China.

Either in the history of the world or in the history of China,the introduction of Buddhism in China is an event of the greatest importance. Although in the ancient Chinese accounts there are many accounts of the introduction of Buddhism yet they are so contradictory to each other that we cannot make a clear idea from them(T'ang Yung-tung,Han wei leang tsin nan pei caho fo kiao she ,Ⅰ,pp. 1-15). Towards the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th the European scholars sent several expeditions to Central Asia. They discovered among the ruins of ancient cities and temples numerous manuscripts,paintings etc. Since then they made epoch making progress in the study of the history and geography of Central Asia and also in the study of the history of Buddhism. Prof. Sylvain Lévi proved that the technical terms in the Chinese translations of the Han period did not come directly from Sanskrit but through a medium,which was according to him a Central Asian medium(Le Tokharien B,Langue de Koutcha ,J. As. 1913,pp. 311 ff). We find records in ancient Chinese literature which amply confirm his views.

I have tried to show that the Chinese Fo does not come directly from Sanskrit but through Kuchean. This goes to strengthen the theory of Prof. Lévi. The other word Fou-t'u which was used in Chinese earlier than Fo came directly from India most probably from an Indian dialectal form. How to explain this fact?Anyhow the theory of Prof. Lévi must be supplemented. We do not know exactly when the Chinese first received Buddhism. Buddhism must have come to China earlier than what is usually believed. It first came either by sea or by land. If it had come by land through Central Asia,the small countries in Central Asia did not yet play any part in the transmission. Chinese translations were made at that time from texts written in Prakrit. The Sūtra of the 42 Sections was one of them. The name Fou-t'u came to be used at this time. It was towards the end of the Han period that Central Asian monks and laymen came to China. They were Ngan She-kao,Che-k'ien,Che Lokakṣema,Ngan Hiuan,Che Yao,K'ang Mongsiang etc. Buddhism began to be transmitted to China by the Buddhist monks of Central Asia. The texts which they translated into Chinese seem to be have been not Indian but written in their own languages. The word Fo came to be used in this period. Dr. Hu Shih says“I suppose boldly that the term Fo came to be used under the latter Han dynasty,when the number of translations and Buddhists began to increase”(ibid,p. 181). I entirely agree with his assertion.

We now come to question of the authenticity of the Sūtra of 42 Sections,and its bearing on the use of the terms Fou-t'u and Fo. So far as the Sūtra is concerned Dr. Hu Shih and Prof. T'ang have discussed the problem thoroughly. I will confine my attention only to one of the points raised by them. Prof. T'ang contends that there were two translations of the Sūtra of 42 Sections and that the existing one in the Chinese Tripit·aka is in too fine a style to be a Han translation. He thinks that the Han translation which was in a plain and simple style was lost. The second translation of the text,that by Che-k'ien of the Wu dynasty,which is in a more refined style,has come down to us(T'ang,loc. cit .Ⅰ,p. 36). Dr. Hu Shih agrees with this theory(loc. cit .p. 178). To me also the theory appears to be very plausible. But one point still remains unexplained. Siang Kiai in his memorial to Huang-ti says“Fou-t'u does not sleep for three nights under a mulberry tree. He does not want to remain there longer lest he may have love for it. This is due to his utmost exertion. The god sends him beautiful girls. Fou-t'u says‘these are only leather sack with blood’. He does not look at them. He is so devoted to his asceticism”(Hou Han Shu ch. 60b). In the Sūtra of the 42 Sections we find similar expressions:“He eats only once a day;he remains under the tree only for one night,he never repeats. What blind the people are the desire and the ignorance(Taisho ed. XVII,722b).“The god offers the Buddha a beautiful girl in order to try him. The Buddha looks at the Tao and says‘you are a leather sack with dirts;why have you come?You can cheat with the common people but cannot shake me who has got six spiritual powers”(ibid,723b).

A comparison shows that Siang Kiai was most probably drawing upon the Sūtra of the 42 Sections. Both Dr. Hu Shih(ibid. p. 171)and Prof. T'ang(ibid. p. 33f)are of this opinion. But Prof. Chen on the contrary contends that“to remain for one night under a tree”and“leather sack with dirts”are of common usage among the Buddhists. The quotation of Siang Kiai,according to him,does not necessarily come from the Sūtra of 42 Sections(ibid. 179). Moreover he points out that Siang Kiai uses the term Fou-t'u in his memorial but it is Fo which we find in the Sūtra of 42 Sections. Dr. Hu admits that there is much force in this contention. Prof. T'ang tries to explain it thus:“The old Chinese books were transmitted only through copies. A term like Fou-t'u does not represent exactly the original name. Besides the Chinese words literally convey a sense of despise. In course of repeated copying the old was changed into a new one(ibid. p. 36).

Now that we know that the source of Fou-t'u was an Indian dialectal form and that of Fo was Kuchean,we can look at the problem from a new point of view. A satisfactory explanation of the problem may be found by having recourse to a new hypothesis. We know that the Sūtra of the 42 Sections was twice translated into Chinese. The first translation which was done in the Han period was based on an Indian original. This translation used the term Fou-t'u and Siang Kiai's quotation was from this translation. This translation was subsequently lost. The second translation,that of Che Kien has come down to us. The original of this translation must have been in some Central Asian dialect.

We thus find that the three principles that were enunciated by Prof. Chen are not based on very strong grounds. He has overlooked the fact that the use of the two names Fou-t'u and Fo concerned chiefly a difference in sources. Simply for the fact that some of the Han translations use only Fo and not Fou-t'u we cannot consider them as not being Han translations. His contention that“even if they are translations”cannot also be supported.

Prof. Chen besides pointed out that Fo is not used in the historical materials used by Fan Wei-tsong. Dr. Hu Shih gives a reasonable explanation of this fact thus:“Yu(chüan),Ch'en(sho),Sse Ma(p'iao)and Fan(Wei Tsong)etc.were all non-Buddhist historians. From the fact that they used only Fou-t'u and not Fo or probably Fo in some cases,we cannot infer that the Buddhists of those days had not yet used Fo as common term for Buddha”(ibid. p. 195). The Chinese scholars and historians borrowed the word Fou-t'u from such texts as had been directly translated from Indian sources. The word Fo was brought later by the Central Asian monks and at the beginning it was confined only to the texts translated by them. Later on it became a word of common use and replaced Fou-t'u on account of its apparent advantages.

(SinoIndian Studies )

注释:

[1] —[5] 佛陀、浮头、部多、没驮、浮屠、佛图、物他、浮陀、勃陀、部陀、佛驮、复豆、佛、馞陀、浮图、勃驮、母陀、步他、母驮、步陀、没陀。