Preface

Among all the Buddhist sūtras,including Hīnayāna and Mahāyāna,the Mahāyāna Saddharmapuṇḍarīkasūtra can be considered as the most influential and prevailing one. In Nepal there prevails a term“nine jewels of Mahāyāna”and Saddharmapuṇḍarīkasūtra is one of them. In the Asiatic countries which are more or less related to Buddhism a large number of manuscripts and printed books of this sūtra are still well preserved. Besides there are numerous manuscript remains discovered from sand-buried temples and pagodas. To these may be added the translations in different archaic and new languages. All this shows clearly that the Saddharmapuṇḍarika prevails widely and has a great influence everywhere in Asia.

The Sanskrit text we have published in a photomechanical printing and now in transcriptions was originally preserved in Tibet of China and now kept in the Library of the Cultural Palace of Nationalities,Beijing. All scholars of Indian Buddhism know that different things account for the disappearance of original Sanskrit Buddhist manuscripts in India. Formerly Nepal was the only known country where Buddhist manuscripts are still preserved. For a long time Nepal was looked upon as treasure-house of original Sanskrit sūtras. This treasure-house has been explored thoroughly by scholars of different countries in the past hundred years,with the result that actual state of Nepal preservation has become known to all and thereby the Sanskrit scholars are provided with numerous valuable materials for their research works. Thereafter according to the calculations of scholars well acquainted with the facts concerned,there remains in the whole world,including India,only one treasure-house of Buddhist manuscripts more,that is Tibet of China. Although there were from time to time foreign intruders to this treasure-house,such as Rāhula Sāṇkṛtyāyana of India and Giuseppe Tucci of Italy,who carried away some Buddhist manuscripts and compiled a few catalogues,yet all that they have explored comprises only a small portion of this treasure-house. Generally speaking,the complete picture of the treasure-house remains still a myth to all of us. Till now we have not yet tried to acquaint ourselves with the total collections of Sanskrit manuscripts,let alone cataloguing. We must admit that this fact causes a lot of inconveniences to the Sanskrit study of the world. All the Sanskrit scholars are really very sorry for this inconvenience.

Now,many Sanskrit and Tibetan scholars in China are taking notice of this problem. We are trying to organize man power and material resources in order to carry on some necessary investigations into the only treasure-house of valuable Buddhist and other manuscript remains in the world. We shall try to select some only existing copies of Buddhist sutras and those copies though not only existing yet very valuable and try to edit critically and publish them in photomechanical printing and in transcriptions in order that the scholars of the world who are engaged in the study of ancient Indian culture and religions may have the opportunity to make use of them. Besides Buddhist sutras we shall also include some Brahmanist texts and even some works of natural sciences. I am firmly convinced of the fact that our collegues all over the world will welcome and appreciate our work. The Sanskrit Saddharmapuṇḍarīkasūtra which we are publishing now is the first book,which will be followed by other books.

This text is neither the only text extant,nor the oldest one. But in comparison with other texts it has its own characteristics and merits,and therefore its own value. Some scholars have proposed that a Buddhist sutra spreading far and wide among the Buddhists of different countries like the Saddharmapuṇḍarīka should have a critical edition. All the extant editions including that edited by H. Kern and B. Nanjio can not be considered to have come up to the standard of a critical edition. If any scholar of any country would incline to such an enterprise,our edition would be very helpful to him.

So far the introduction of the Sanskrit Saddharmapuṇḍarīkasūtra of the Library of Cultural Palace of Nationalities. Regarding the details see also the introduction of Comrade Jiang Zhongxin.

By the way,I would like to discuss a problem here,i.e. the linguistic characteristics of the Sanskrit Saddharmapuṇḍarīkasūtra. In 1941 I wrote an article:Die Umwandlung der Endung -aṃ in -o und -u im Mittelindischen. NAWG 1944,Nr. 6,S. 121—144. In this artical I tried to set up a hypothesis that the Saddharmapuṇḍarīkasūtra was originally written in so-called Ardhamāgadhī,an Eastern dialect of ancient India,but afterwards Sanskritised step by step and in the meantime some characteristics of northwestern dialect made their appearance,for example,-aṃ>-o and -u. The discrimination of linguistic characteristics will be helpful to the study of text evolution of Saddharmapuṇḍarīkasūtra.

My hypothesis meets with criticism of the famous German Sanskrit scholar Prof. Heinz Bechert of Göttingen. He said:

“Es bedarf wohl keiner langen Ausführungen um darzutun,daß diese Theorie von H. Dschi nicht mehr aufrechterhalten werden kann. Die Gilgithandschrift enthält nach Ausweis der von W. Baruch edierten Blätter keine Formen auf -u;es ist daher wahrscheinlich,daß sie erst im weiteren Verlauf der Textgeschichte in die Überlieferung gelangt sind. Damit aber entfernen wir uns so sehr von der mittelindischen Grundlage des Textes,daß wir keine Schlußfolgerungen mehr auf die frühe Periode ziehen können,von der bei Dschi die Rede ist.”(Über die“Marburger Fragmente”des Saddharmapuṇḍarīka. NAWG 1972,Nr. 1. S. 79.)

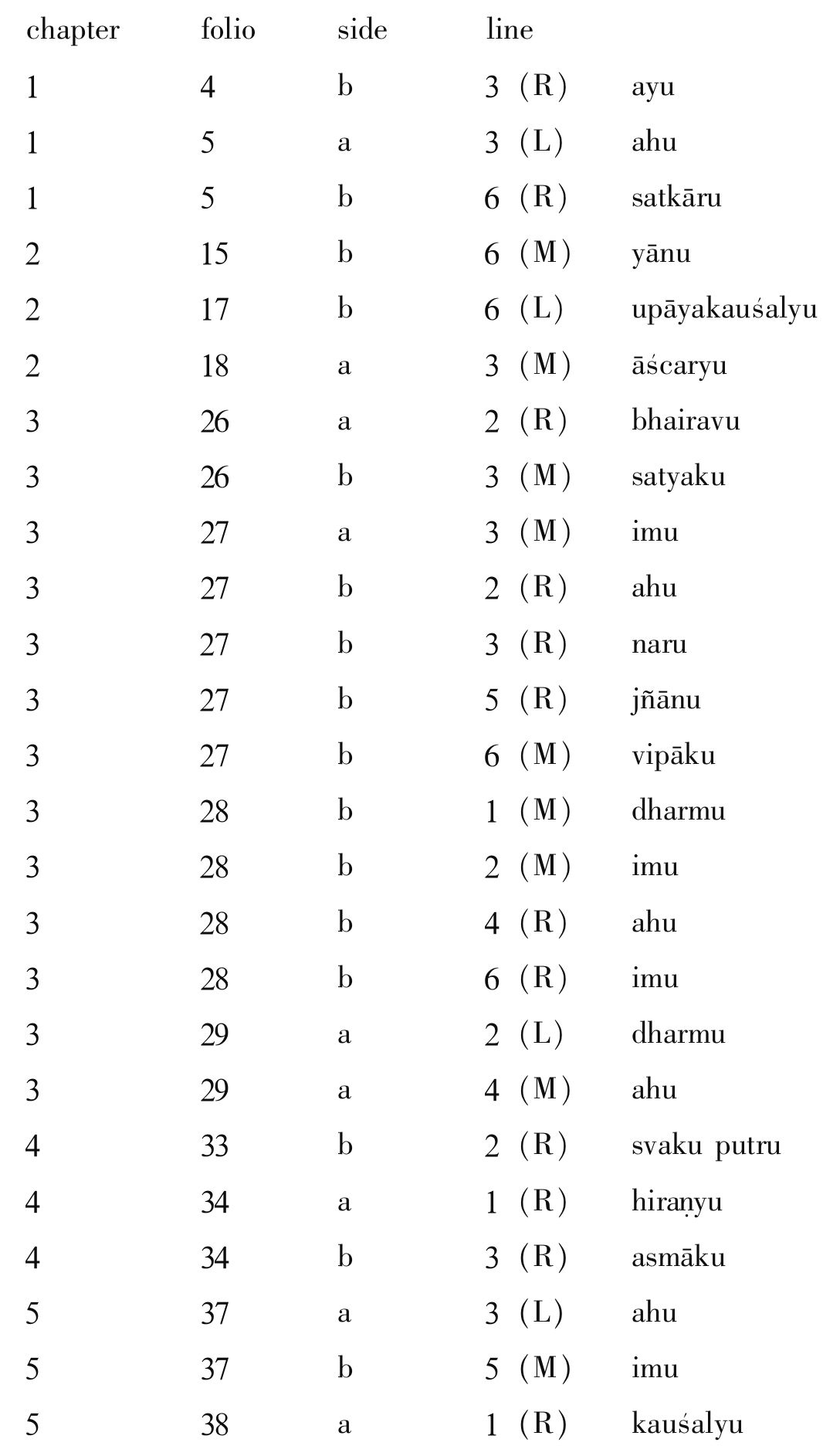

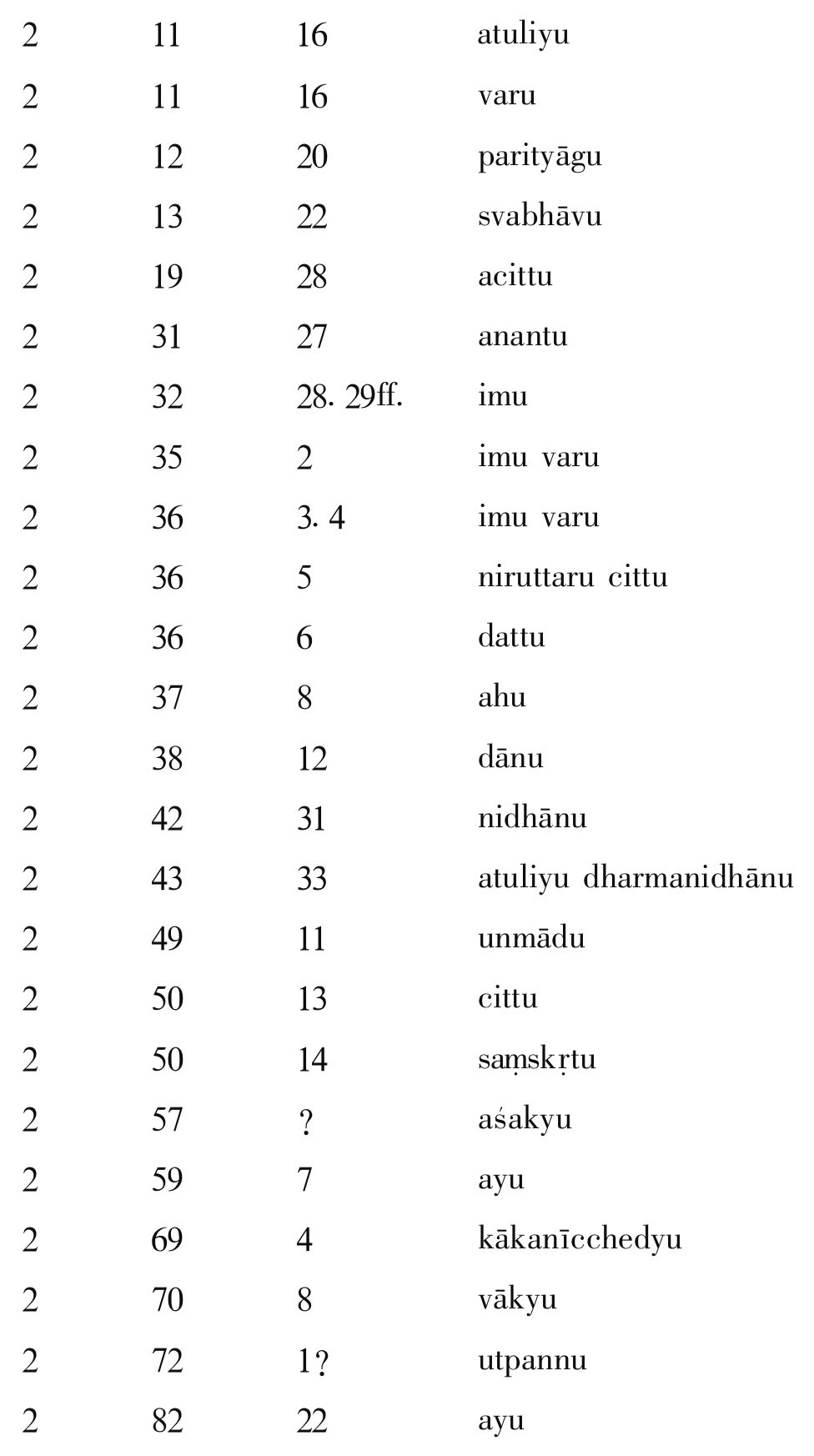

To speak the truth,I was really astonished at the conclusion of Prof. Bechert. His only grounds are the few leaves of manuscript remains of Saddharmapuṇḍarīkasūtra discovered in Gillgit and edited by Prof. Baruch. He said there is no transformation of -aṃ into -o and -u in them. But the fact is that the very first word in the very first line(i)mu shows already the transformation of -aṃ into -u. [1] The Japanese scholar Prof. Shōkō Watanabe published in 1975 Saddharmapuṇḍarīka in Sanskrit original,in which he includes also the above-mentioned few leaves of manuscript remains edited by Baruch. [2] Now I quote a few examples from Watanabe's edition all belonging to the XI chapter called Stūpasaṃdarśanaparivartaḥ [3] :

imu<imam[3].[4]

dharmaparyāyu<dharmaparyāyam[10]

sūtru<sūtram [4] [31]

Therefore,however unwilling I may be,I must still say that Prof. Bechert came to his hasty conclusions in a light-minded hurry. As regards the expression of Prof. Bechert:

“Damit aber entfernen wir uns so sehr von der mittelindischen Grundlage des Textes,dass wir keine Schlussfolgerungen mehr auf die frühe Periode ziehen können,von der bei Dschi die Rede ist”.

I must point out here that the transformation of -aṃ into -o and -u in Saddharmapuṇḍarīkasūtra is comparatively rather late,but in the history of Indian Languages this phenomenon is not only not late but rather early. In the above-mentioned paper of mine at the very begining I expounded the transformation of -aṃ into -o and -u in the Northwestern version of Aśoka inscriptions. This distinguishing linguistic feature is absolutely true and can raise no doubts at all. This feature appeared not late and it has nothing to do with rhymes and metres. The explanation of Prof. Bechert can by no means be applied here. Besides,we do not have any eloquent proof that its appearance is specifically late. In a word,the opinion of Prof. Bechert can by no means be considered as tenable.

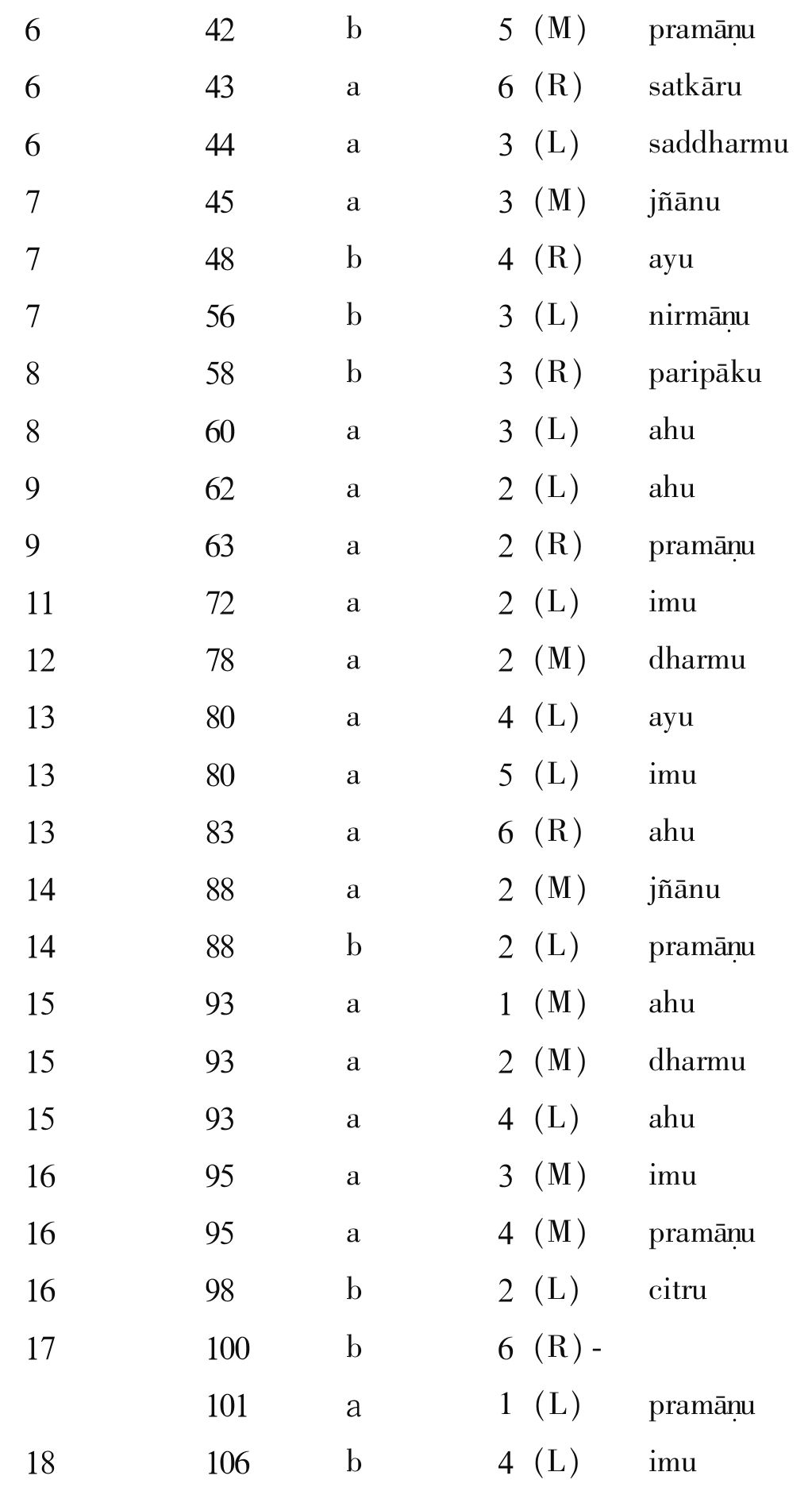

Now in this Saddharmapuṇḍarīkasūtra version of Tibet just as in the Nepalese version(both came from the same source). We can find quite a lot of transformations from -aṃ into -o and -u. In the following I select a few examples from each chapter: [5]

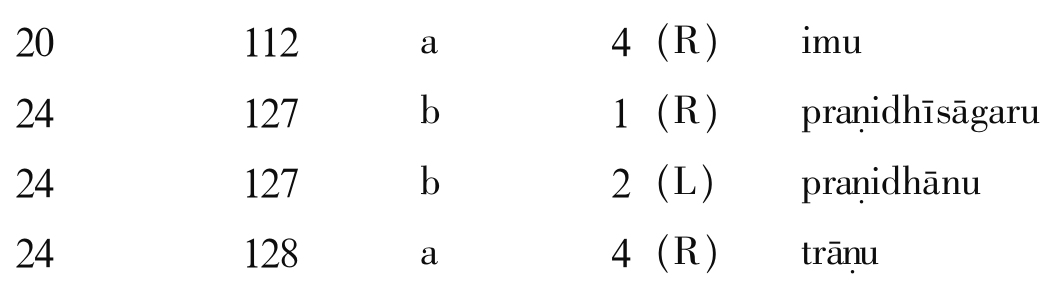

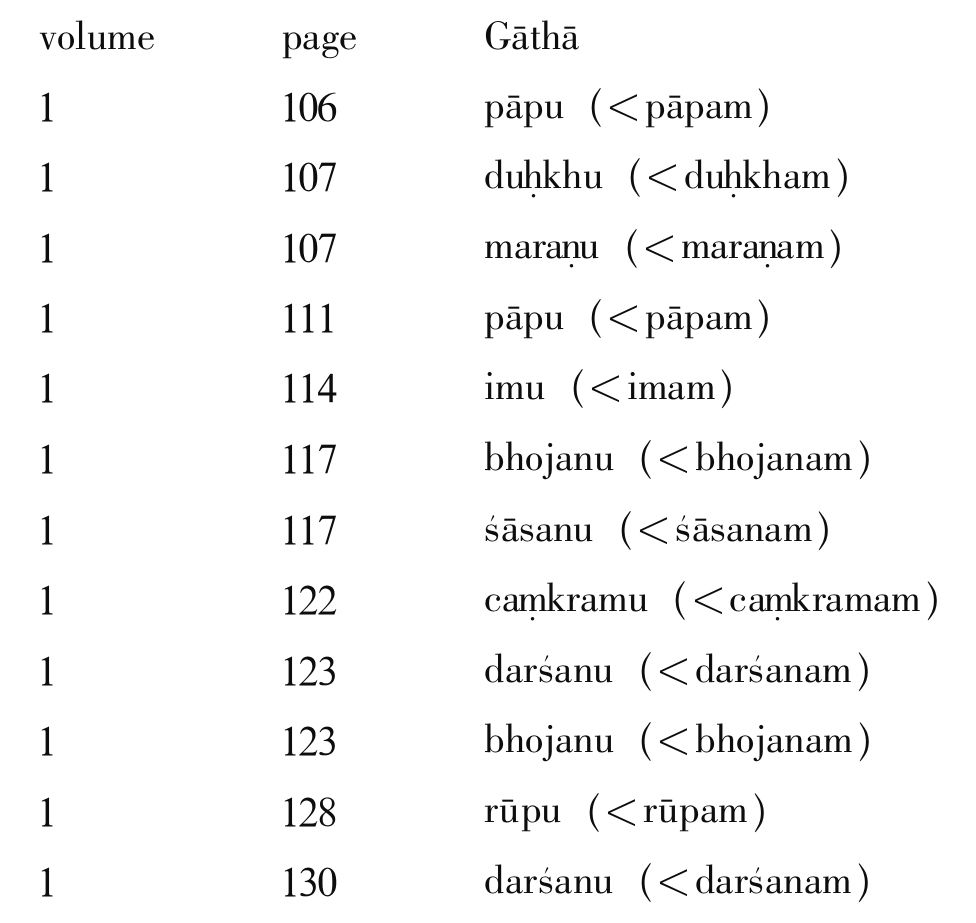

Besides Saddharmapuṇḍarīkasūtra,we find also in the Gāthās of other Gilgit MSS many transformations -aṃ>-u. I now give some examples:

(A)Ajitasenavyākāraṇam

(B)Samādhirājasutram

I have given so many examples above. I would like to do nothing but to prove only one fact:-aṃ>-u and -o is the most prominent of the morphological characteristics of Northwestern dialect in ancient India. Cf. John Brough,The Gāndhārī Dharmapada. London 1962;J. W.de Jong,Buddhist Studies,Berkeley,California,1979,p. 290,note 8 and K. R. Norman,Pāli and the Language of the Heretics,Acta Orientalia,XXXVII,1976,p. 124,note 34. In the Gilgit manuscripts we can find many such characteristics,especially in the Gāthās. In many Saddharmapuṇḍarīka manuscripts we find the same characteristics. Therefore,my conclusion remains the same as forty years ago:Saddharmapuṇḍarīkasūtra originally written in an Eastern dialect adopted during its migration from one place to another some Northwestern morphological characteristics by and by,including the transformation -aṃ>-o and -u. In another word this Sūtra was influenced by Northwestern dialect.

November 4,1981